Shelley B. Wepner

Manhattanville University

William A. Henk

Marquette University

Nora C. R. Broege

Manhattanville University

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Shelley B. Wepner, Manhattanville University, shelley.wepner@mville.edu

Abstract

High turnover rates with college and university presidents make longevity an important matter for higher education. This paper provides a conceptual framework that identifies factors affecting presidents’ ability to stay in their positions, especially when their longevity is desirable. The framework builds upon 26 years of previous work involving the leadership practices, characteristics, and longevity of education deans, academic deans, and Chief Academic Officers. Four major categorical factors, both internal and external to self, are described that contribute reciprocally to presidents’ ability to last on the job. These four factors—personal identity, professional identity, professional capacities, and professional environment—are connected with each other and intersect with the maturing of one’s ego so that one has the capacity to adapt appropriately to situations. This framework begins to develop a portrait of critical leadership characteristics needed for success and satisfaction with the most prominent position in higher education.

College and university presidents serve as both the chief executive and administrative officers and are responsible for all aspects of their organizations (Schreiber, 2020). These higher education leaders have multifaceted roles and responsibilities that require synthesizing and applying knowledge in a visionary way to forward the college or university’s goals and ensure the effective operation of the institution (Lynch, 2018). Presidents must be able to relate to, grasp, and appreciate all academic and administrative areas in the institution. Of special importance, they are ultimately accountable for managing the college or university finances and ensuring solvency through their enrollment and fundraising efforts.

Presidents usually retain an advisory cabinet of vice presidents, or an executive leadership team, along with other key individuals who help with broad areas of responsibility including academic affairs, alumni engagement, communications, enrollment management, facilities, finances, fundraising, human resources, library, public and governmental relations, safety, student affairs, and technology (Duesterhaus, 2022). Their advisory cabinet as well as other well-positioned professional colleagues within the institution can and should alert them to problems that need to be addressed before getting out of hand (Weyandt, 1996). Although assisted by their advisory cabinet, presidents are responsible overall for employees’ work lives and must address issues and emerging crises swiftly, professionally, ethically, transparently, and compassionately (Bowles, 2013).

MacTaggart (2017) referred to 21st-century college presidents as the enterprise leaders who not only lead change but manage it. They must clearly understand the new and unprecedented challenges confronting their campuses and commit to strengthening their institutions over time. This ability to do so takes on added significance because it figures to lead to their own job satisfaction and presumably the duration in their positions (Bruns, 2018). Their roles include strategists, communicators, storytellers, fundraisers, and collaborators who understand that interpersonal relationships are paramount to success (Romano, 2020). Moreover, they understand that their colleges and universities almost inevitably reflect the tensions and conflicts in the broader society, and that social media has substantially amplified the voices of those who are most critical. According to Handel (2021), while confident presidents can learn and grow from mistakes, especially public ones, those with less confidence typically cannot.

Presidents must also develop effective and credible messaging for their board members, donors, lawmakers, community members, parents, students, faculty, and staff (Bowles, 2013). Sometimes referred to as police officers who protect and serve, as well as boxers who have the agility, stamina, and fitness to take a punch both physically and metaphorically, a president’s gift of communication should inspire hope and promise in a compelling, heartfelt, and intelligent voice (Bowles, 2013).

In addition, presidents need to be energetic, avid listeners, and tolerant of ambiguity for their various constituencies. They should be able to adapt to a variety of situations, based on the information that they both have and continue to acquire about their institutions through observation, immersion, peer guidance, and mentoring (Matthews, 2021; Smerek, 2013). Their interest and ability to remain in their positions depends largely on understanding and appreciating the context in which they work, the nature and magnitude of their positions, and the essential personal and professional characteristics that lead to professional and personal success. Accordingly, this article centers on the interrelationships among key variables that collectively contribute in large measure to effective presidents’ longevity in their roles.

Longevity of College and University Presidents

The average length of service for a college or university president is 5.9 years (Jesse, 2023), which exceeds those of most chief academic officers and academic deans who each average 4.6 years (Clayton, 2019; Zackal, 2022). Yet, research indicates that presidents’ “shelf life” is shorter than the length of what their tenure has typically been over the last several decades when the average duration amounted to 6.5 years in 2016 and 8.5 years in 2006 (Finkelstein & Wilde, 2021; Jesse, 2023). As it turns out, more than half of all presidents leave their current posts within five years (Gagliardi et al., 2017) to pursue consultant roles, return to the faculty, work in nonprofits outside of higher education, or find other opportunities more appealing than their current work responsibilities (Jesse, 2023; Zackal, 2022). Some also depart quite abruptly because of financial misconduct, scandals, disagreements with their governing boards, or for personal reasons (Doss Bowman, 2017).

Although some variation exists in the reported average age of presidents, the number tends to fall around 61 or 62 years, with evidence that more presidents are being hired between the ages of 41 and 50, as well as ages 70 or older (McNaughtan, 2016; Whitford, 2020). An escalating trend in higher education points to presidents growing older and serving less time in their positions (Paterson, 2018). These trends seem to be influenced by financial woes that were exacerbated by the pandemic and the shifting demographics of students who need robust financial aid and flexible programs (Whitford, 2020). There also is evidence that presidents are assuming more than one presidency over the course of their careers, especially those coming from public universities (Monks, 2012; Reid, 2018).

Bornstein (2003) identified six leading threats to the success of college presidents including: (1) misfitting with culture, (2) managerial incompetence, (3) erosion of social capital, (4) inattentiveness, (5) grandiosity, and (6) misconduct. Each of these threats can cause presidents to lose their legitimacy and eventually their positions. Additional causes of involuntary presidential turnover center on financial tempests, loss of board confidence, a decline in faculty and staff confidence, athletic controversies, misgivings about the system, and poor judgment (Harris & Ellis, 2018).

The staying power of those presidents who remain in their positions for long periods of time derives primarily from having leadership styles that fit with the institutional culture, focusing their visions in relation to available resources, enjoying trusting, cooperative, and reciprocally influential relationships with their stakeholders, attending to their institutions’ internal operations, appreciating shared governance, stewarding with strong moral compasses, and managing to avoid major conflicts and controversies. These enduring leaders tend to have strong support from their Boards, groups who play the most pivotal role in whether presidents are retained in their roles (Rutherford & Lozano, 2018). Presidents who have staying power also seem to have found ways to manage stress by adopting positive mindsets and repeatable practices of self-care and reflection (Thacker & Freeman, 2020). Their job satisfaction and performance are high, largely because their personal situations align with their institutions’ demographics and culture (Perrakis et al., 2011).

Of primary interest here are speculations about why most presidents remain in or exit their administrative positions, and characteristics that contribute to their staying power. As Song and Hartley (2021) argued, additional research needs to be conducted about reasons for the decline in presidential lengths of service. In effect, responses to this query address the construct of longevity (i.e., in this instance the duration of time in the position of a president or chancellor) and the potential impact that endurance in the office exerts on the growth and development of their institutions as well as their own welfare. Although many contextual factors affect one’s longevity, short duration in the role could very reasonably reflect the lack of essential leadership characteristics.

Specifically, this article provides a conceptual framework that identifies factors affecting presidents’ ability to stay in their positions, especially when their longevity is desirable, and not to advocate for longevity in the position per se. This framework presupposes that presidents can make such decisions for themselves rather than having them made elsewhere. Given that presidents’ longevity most likely depends on the individuals and their specific professional context, the degree to which they can navigate conditions that are most pressing for the institution figures to determine how well they can thrive in their particular work environments.

Impetus for the Conceptual Framework

This framework builds upon 26 years of previous work involving the leadership practices, characteristics, and longevity of education deans, academic deans, and chief academic officers (CAOs) (Henk et al., 2017, 2021a, b; 2022; Wepner, D’Onofrio, Willis, & Wilhite, 2002, 2003; Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Wilhite, 2004, 2008; Wepner & Henk, 2020, 2022; Wepner et al., 2012, 2014, 2015, 2020, 2022; Wepner, Wilhite, & D’Onofrio, 2002, 2003, 2011; Wepner, Hopkins, Johnson, & Damico, 2011). Among those studies, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE), in partnership with the researchers, hosted three national surveys related to education deans, with the final one focusing on longevity. In a subsequent partnership, the American Conference of Academic Deans (ACAD) and the Council of Colleges of Arts and Sciences (CCAS) hosted a longevity survey of a wider spectrum of academic deans. Likewise, the American Conference of Academic Deans (ACAD), the Association of Chief Academic Officers (ACAO), the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU), and the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (APLU) hosted a longevity study of provosts, CAOs, and vice presidents for academic affairs or their equivalents.

The findings from these surveys of 181 education deans, 272 academic deans, and 316 CAOS gave rise to the notion that job satisfaction, and conversely job dissatisfaction, emerged as the multifaceted overarching conception for remaining or exiting their positions. This conceptualization includes a number of factors, including the capacity to do the job, enjoying authority and empowerment, being valued, appreciating the culture of the institution, coping successfully with the influence of external forces, and envisioning professional growth opportunities (Henk et al., 2017, 2021a, b, 2022; Wepner & Henk, 2020, 2022; Wepner et al., 2020, 2022).

Survey findings further indicated that their relationships with and support from their immediate supervisors, their faculty, and their staff were the most salient influences on their feelings about job satisfaction. How these administrators assessed their leadership, and in relation to their capacity to work with others, were also considered imperative for continuing in their role. Factors such as the ability to make a noteworthy difference, feeling relevant, trusted for their leadership to provide stability, still having goals to accomplish, and finding joy and satisfaction in the position were rated highly for overall job satisfaction. These leaders also recognized the need to be physically, mentally, and emotionally healthy (Henk et al., 2017, 2021a, b, 2022; Wepner & Henk, 2020, 2022; Wepner et al., 2020, 2022).

Previous qualitative and quantitative studies of 245 education deans’ characteristics, practices, and beliefs were the impetus for studies about longevity because they revealed the importance of certain attributes and psychological traits to function effectively. The interviews, case studies, vignettes, and surveys deployed across these studies indicated that the ability to work successfully with others required an interconnectedness of intellectual, social, emotional, and moral competencies. (Wepner, D’Onofrio, Willis, & Wilhite, 2002, 2003; Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Wilhite, 2004, 2008; Wepner, Wilhite, & D’Onofrio, 2002, 2003). Such an interconnectedness appeared to stem from a self-awareness that had developed over time (Loevinger, 1976).

The original studies were prompted by a belief that success in an executive leadership position had as much to do with interpersonal competence as technical competence. Having observed, worked with, or heard the stories from many individuals who were pushed out of their positions, the researchers noted an apparent disconnect between what they believed about their role and about themselves and what their stakeholders wanted and expected from them. These leaders did not seem to be aware of the consequences of their actions on others and did not seem to have been able to reflect on the impact of their decisions in their work environments (Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Wilhite, 2008).

Real-life situations that typically happen at a college or university were used to understand veteran deans’ problem-solving approaches. Such situations included faculty displaying hostile and unprofessional behavior, a search committee at an impasse about hiring a diverse faculty member supported by the Board of Trustees (BOT), and intergenerational strife among faculty around curriculum initiatives.

Analyses of deans’ responses to these situations led to the central concept of a mature ego that relied on specific components within four dimensions. Loevinger’s theory of ego development (1976) provided the framework for studying the four dimensions, namely intellectual, emotional, social, and moral. The intellectual dimension involved an ability to define problems, seek information related to the problems, and make decisions with an understanding that they and others function differently. They depended on this dimension to tolerate perplexity and transcend polarities. The emotional dimension related to appreciating how one’s values control one’s behavior, committing to and expressing one’s values and feelings, being responsive, and acknowledging inner conflict in relation to needs and duties. The social dimensions focused on an ability to work with and build upon relationships, cope with conflict, cherish personal ties, and tolerate self and others. The moral dimension encompassed an understanding of the importance of justice, duty, virtue, well-being, and consequences.

Although all components of each dimension were used, there were certain elemental components that were used more frequently. Notably, these executive leaders used, first and foremost, the intellectual dimension to define problems. In doing so, they indicated their ability to understand and appreciate different perspectives. For example, although they might have believed that certain programs needed to be cut because of declining enrollments to make room for new programs with potentially high-yield enrollments, they understood that others did not necessarily share the same beliefs because of their own experiences with such programs. These leaders had the ability to appreciate others and their views and, rather than make arbitrary and unilateral decisions, they considered the impact on others.

They drew upon their emotional dimension by appreciating others and expressing their feelings and values vividly and convincingly. They anchored their understanding of situations, challenges, and problems by answering to their social and moral contexts, specifically considering the importance of interpersonal relationships and organizational responsibilities (Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Willis, 2008).

These leaders communicated that they were strategists in that they defined problems, knew to work within existing relationships, were aware of the importance of emotion as they made decisions, and had a sense of duty to their role and their institution. They knew unwittingly when to depend on one dimension over the other (Loevinger, 1976). Their skills, attitudes, and dispositions reflected their self-awareness and professional self-concept for serving in such a role (Wepner, D’Onofrio, Willis, & Wilhite, 2002, 2003; Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Wilhite, 2004, 2008; Wepner, Wilhite, & D’Onofrio, 2002, 2003).

Studies have shown that one’s professional self-concept is developed over time through personal and interpersonal experiences in the workplace (Bracken & Lamprecht, 2003; Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987). Different experiences and interpersonal dialogues affect how individuals interpret their roles as leaders. When leaders can reflect on these encounters, they become self-aware of both their interpersonal and technical competence.

Their interpersonal competence comes from an openness to learning about the traditions, norms, and expectations of their professional culture. Their technical competence comes from mastering the skills required to do the job. Leaders with self-aware self-concepts understand themselves and their competencies in relation to others. They can visualize the implications of their values and the consequences of their goals, actions, and problem-solving strategies on others. They come to understand the need to adapt to their environments in a way that promotes balanced problem-solving approaches (Ashmore & Contrada, 1999; Bandura, 2000; Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1989; Loevinger, 1976; Mischel, 1973; Mischel, et al., 1989; Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Wilhite, 2008).

Characteristics that Contribute to Longevity: A Conceptual Framework

As with deans and CAOs, presidents must positively and proactively navigate their relationships with their immediate supervisors, faculty, and staff. Presidents are held responsible for their leadership by their BOTs. In concert with executive leadership teams, presidents must demonstrate to their BOTs that they are steering their academic ships to reach full potential on behalf of students. Presidents’ ability to navigate these waters depends on their capacity to cultivate their stakeholders so that they move in the same direction. If stakeholders are strategically cultivated to generate support for the institution’s direction, presidents can continue to sail in their positions; in other words, job satisfaction is visible, and longevity is on the horizon.

However, as many presidents have come to learn, institutions can become surprisingly difficult to navigate when political situations become turbulent. Presidents can be celebrated one minute and criticized or even vilified the next. One president relayed how this happened to her in a “can’t win” scenario. She had been thriving for five years, especially because of her ability to raise funds to beautify the campus. She found herself in a defensive political climate because of succumbing to pressure from an affluent group of donors who wanted her to invite a well-known, politically controversial figure to speak. Her faculty were incensed when they discovered that she would allow this speaker onto campus to espouse what they considered to be extreme partisan views to impressionable undergraduate students. The faculty threatened a walk-out if she did not cancel the event. She realized that her excitement for the funds that would come from the event blinded her ability to see the negative impact on her faculty, staff, and students. She owned her mistake to both sides. She disseminated an apology on video and held live sessions to answer questions. She received “hate” mail from very angry supporters of the speaker. She also saw a huge decline in donations from the speaker’s supporters, which angered members of her board of trustees (BOT). Nevertheless, she took responsibility for her lapse in judgment by apologizing wherever appropriate and continued to move forward unabashedly with the many goals that she had established. Since there were mandatory term limits for board members, she was hopeful that new members would help her to move the institution forward with equanimity.

Although initially swept into the vortex of financial promises, this president’s ability to listen to and appreciate her faculty’s outrage provided her with the wherewithal to admit to herself and her constituency that she had made a mistake. Her professional identity as a president provided her with the strength to communicate repeatedly in a variety of forums about her misjudgment of the situation. She did not let it disable her, but rather strengthened her resolve to keep moving forward. She exemplified someone who could self-reflect with an objective lens her reasons for misjudgment, take responsibility for her ill-informed decision, and communicate publicly and honestly to both political arenas reasons for her reversal.

A Conceptual Framework for Executive Leadership

A president’s ability to accomplish goals reflects an evolving vision that fits with the institutional context, an ability to manage various facets of their goals, and the confidence to forge ahead in the face of financial, personnel, and political roadblocks. To ensure positive outcomes, they must be adept at using interpersonal/negotiating skills to bring ideas to fruition. They need to be agile thinkers who are flexible in accommodating numerous points of view while ensuring that they are pursuing opportunities that do no harm to their institutions. Presidents’ leadership characteristics may be both natural and acquired.

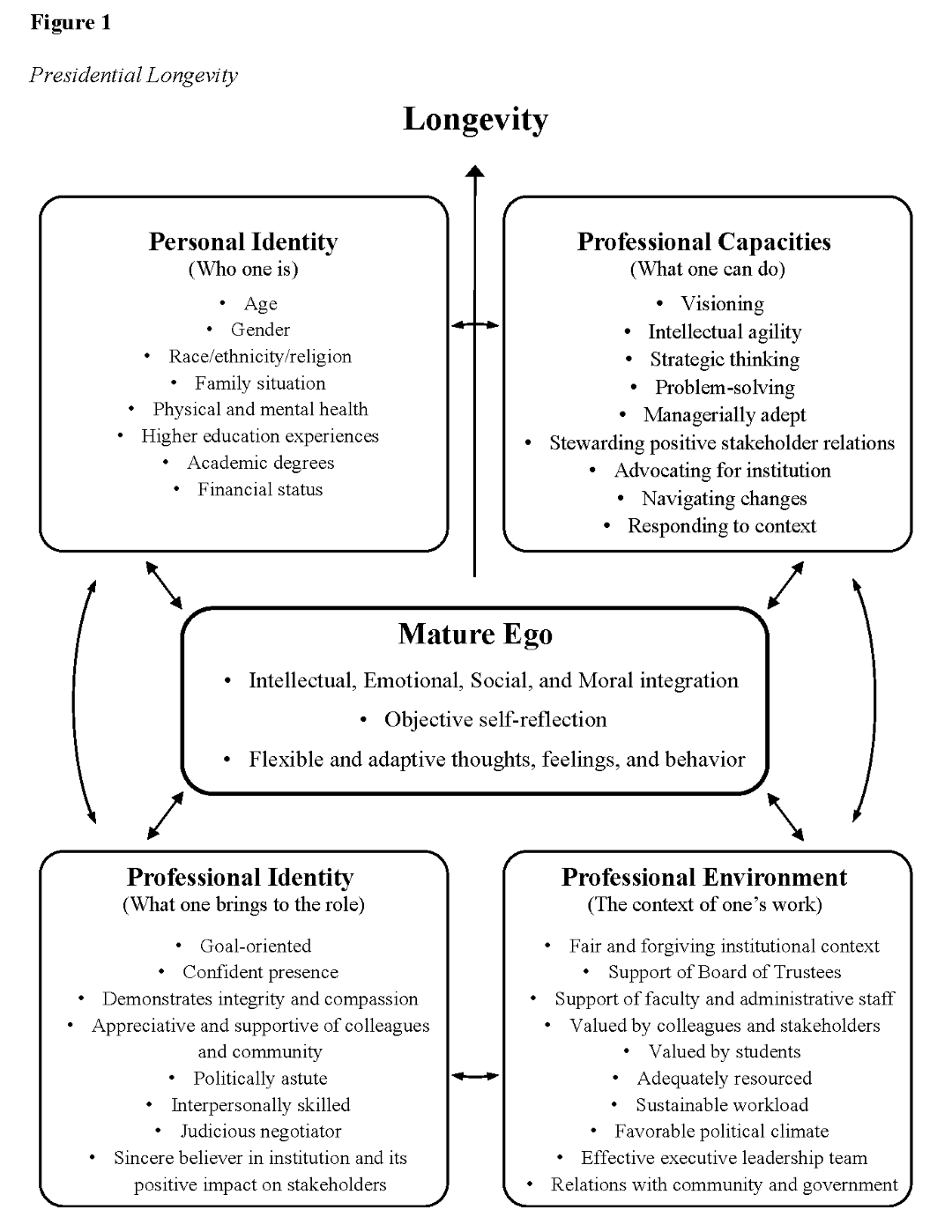

Many factors support or detract from leaders’ ability to succeed. At the heart of effective leadership is the notion of a mature ego which evolves over time if certain inherent characteristics can be tapped. Figure 1 identifies four major categorical factors, both internal and external to self, that contribute reciprocally to presidents’ ability to last on the job. These four factors—personal identity, professional identity, professional capacities, and professional environment—are connected with each other and intersect with the maturing of one’s ego so that one has the capacity to adapt appropriately to situations. A leader’s dependence on one factor over another must be fluid as situations change. This conceptual framework draws from previous research of different types of executive leaders, interviews from five current and previous presidents about their own longevity, and observations of, and stories from, previous presidents at 10 different institutions.

Personal identity, or who one is, describes the president’s biographical profile. It reveals an important narrative of an individual’s sense of identity that is brought to the position. A White, 65-year old Catholic male with a supportive, first-lady-oriented wife and older, self-supporting children will come to the position with an identity different from a Hispanic, 50-year old Lesbian woman whose partner has her own demanding career. Someone who already has served successfully as a president at a similarly situated private institution brings a different identity than one who is striving to move up after serving as a Provost at a more prestigious, public institution.

A president’s academic degrees also tell about their sense of identity, especially in relation to the institution’s mission and status. A president coming with engineering degrees from highly technical universities to a liberal arts college might identify differently than a president who was an English scholar at a similar type of liberal arts institution. Similarly, previous higher education experiences reveal important information. A non-traditional president hired away from the business world or government will view the position differently than a president hired away from an already successful presidency. Veteran presidents looking to secure their finances for retirement versus new presidents looking to build their careers have different motivations that define who they are as well. Their health history, both physical and mental, also indicates an important part of who they are. Although a comprehensive series of interviews, especially by members of the BOT, disclose a president’s personal profile, many facets of one’s personal identity do not get revealed or exposed until that individual occupies the office.

Professional identity, or what one brings to the role, centers on the president’s orientation toward the people, place, and position. It signals the way in which presidents approach the job in relation to their values, beliefs, dispositions, personality, and experiences. Professional identity divulges a president’s orientation toward goals, self-assurance, level of sincerity toward others, interpersonal/negotiating skills, political savviness, and confidence in the institution as they establish and pursue goals to further develop the institution. It is about one’s interpersonal competence.

Patterns of behavior over time uncover a president’s professional identity. Presidents who are not impressed with their institutions’ reputations or are not enamored with their faculty’s productivity most likely will not be as ingratiating as those who are truly smitten by what they find. Presidents who believe that they know best, despite warnings to the contrary from their stakeholders, will not bring to the role the necessary identity for an institution. On the contrary, presidents who value the beauty and potential in their institutions will communicate such a temperament and spirit to their various constituencies in multiple venues; thus, motivating others to follow.

As noted, one’s professional identity is difficult to determine before one assumes the position. Reference checks, conversations with others at previous institutions, and possibly hypothetical situations can provide some insight into a potential candidate’s professional identity. However, only over time will institutional communities come to learn about a president’s match with the institution.

Professional capacities, or what one can do, refers to a president’s ability to actually perform the job. It entails being visionary, strategic, financially savvy, managerially adept, contextually aware, and responsive. It requires intellectual agility, superb problem-solving skills, the ability to navigate change, and capable stewardship of stakeholders and the institution as a whole. The concept revolves around a president’s technical competence. Professional capacities often determine whether a president will be able to continue in the position. Not all presidents have what might be considered ideal professional capacities, particularly with regard to certain positions.

The pandemic highlighted ways in which presidents demonstrated their professional capacities. Not only did presidents have to figure out how to keep their students, faculty, and staff safe, but most also had to address the financial fallout from lost revenue. Salary cuts, furloughs, and layoffs might have needed to be implemented, especially at tuition-driven, less endowed institutions. Some presidents fared fine, but others less adept collapsed emotionally under such enormous pressure. The crisis brought to the fore their capacities for working effectively with their constituencies and navigating their institutions’ needs.

Professional environment, or the context of one’s work, provides the stage for a president’s performance. It is defined by the type and level of support from stakeholders, especially members of the BOT, as well as resource availability, effectiveness of the executive leadership team, the institutional culture and climate, community and government relations, and workload sustainability. Unlike the first three factors, which identify characteristics that presidents bring to their positions, professional environment can affect and alter presidents’ sense of self because it reveals to presidents the degree to which they are valued by their colleagues, students, and other stakeholders. The degree to which they grasp, value, and capitalize on their professional environment determines their level of success in the position. For instance, one president shared that the chair of his BOT did not think that he was innovative and progressive enough. Rather than accede to what he perceived to be unrealistic expectations for the institution, he removed himself from the position.

As Figure 1 indicates, all four categorical factors are interconnected. Presidents’ ability to function depends on who they are, what they bring to the role, what they can do while in the role, and all in relation to where they work. Their ability to self-reflect about their interactions, responses, and decisions with regard to their identities, capacities, and contexts is what enables them to be flexible and adaptable. Self-reflective insights that lead to flexible, adaptive interpersonal and technical competencies contribute enormously to a president’s effective functioning.

Conversations with and observations of presidents who left their positions earlier than the current 5.9 years average (Jesse, 2023) revealed how their inability to discern and face their shortcomings in relation to their contexts affected their job performance which, in turn, affected their longevity. One president conveyed that he discovered shortly after arriving that the financial situation was much worse than portrayed during the interviews. He began the job with big ideas about enhancing the athletic area, but soon realized that funds simply were not available. Simultaneously, he had many members of his cabinet vying for funds to help with woefully understaffed offices; his BOT putting pressure on him to increase the endowment and balance the operational budget; and his faculty complaining about their workload and salaries.

As a new president who had risen from a Provost position, he found himself depending on his own provost and chief financial officer (CFO) to help him develop a strategic financial plan. He realized that his provost was not sincerely interested in helping him because he had wanted his job. He also learned that it was his CFO who had given the BOT an incorrect financial assessment.

Rather than admit to himself and his BOT that he needed assistance to create and implement a short-term and long-term strategic financial plan, he became critical, biting, and reclusive. He blamed members of his cabinet, spoke irreverently to faculty and staff, sequestered himself from students, and bemoaned publicly the institution’s mediocre reputation. He also misled his BOT by presenting creative and calculated approaches that he was using to no avail in addressing the institution’s financial situation. Although the BOT believed him and supported his decisions, they concluded over time that they had erred in hiring him. What’s more they had to give him a generous buy-out package to minimize any further damage to the institution. This president simply could not integrate and adapt facets of his identity and capacities to respond appropriately to his context.

Another president shared a dilemma that he experienced with his vice president for admissions and his vice president for finance. The two vice presidents were bickering daily, disrupting cabinet meetings with their issues, and casting aspersions on each other about being unethical, dogmatic, and irresponsible. After a few weeks of observing this tension, the president realized that he had to intervene. He discovered that it began when the vice president for admissions sent an email to the entire university to report an upward trend in enrollment. The vice president for finance did not have a record of such revenue to support such a claim and thought that his colleague was intentionally inflating the numbers to validate his recent appointment into the position. The president realized that, in touting this new vice president as a savior for upward trends in enrollment, he was inadvertently communicating that this particular vice president carried more importance than other vice presidents. The vice president for finance, a long-term employee, felt threatened by the implication and also saw this new vice president as someone more interested in receiving glory than in learning about the actual revenue. As the president delved into the situation, he realized that there were many delays in the financial aid office, for which the new vice president was responsible, in clearing students to enroll.

This president took it upon himself to address the situation head-on by working with the new vice president and the financial aid office to create a more fluid system for working with students. He met with the two vice presidents together to determine the actual enrollment and revenue as well as with each vice president individually to find out their views of the situation. He brought them together again to ascertain a way to move forward constructively. Finally, he wrote a general letter to the community about current initiatives that included an amendment about the enrollment data so that the community had accurate information.

This president was able to admit to himself that his actions created perceptions of favoritism and ignited feelings of resentment within his own cabinet. He understood that he had affected both vice presidents’ sense of importance, with one feeling empowered and the other feeling disempowered. In addition to inflating the actual enrollment and miscalculating his role in reporting enrollment trends, the vice president for admissions did not appreciate the importance of working collaboratively with his colleagues. The president’s ability to discern the problem, appreciate each vice president’s perspective, work closely with each, and communicate to the campus community helped to avoid undesirable consequences.

Insights and Implications for the Future

As the face of the institution who sets the tone for the academic, cultural, interpersonal, and political climate, presidents often have lifespans in these positions of less than five or six years (Finkelstein & Wilde, 2021; Gagliardi et al., 2017; Jesse, 2023; Zackal, 2022). Such short tenures do not allow enough time for the “ink to dry” on substantial presidential initiatives because of threats to longevity (Bornstein, 2003; Harris & Ellis, 2018). Those who manage to stay beyond the average length of time typically possess the necessary leadership characteristics and self-reflective practices to garner widespread support from their institutional stakeholders, including their BOTs (Perrakis et al., 2011; Rutherford & Lozano, 2018; Thacker & Freeman, 2020).

The conceptual framework presented in Figure 1, drawn from previous research and interviews, stories, and observations of presidents, is offered for possible consideration as fodder for research into presidential longevity and effectiveness with the caveat that the factors included within each category are not exhaustive. As the figure indicates, presidents bring to their institutional environments various personal and professional identities and a range of capacities. Some identities are essentially fixed (e.g., age and race/ethnicity/religion) and some are more flexible (e.g., visioning and confident presence). Presidents differ on what they bring to the role and what they can perform and accomplish. Some might excel at visioning and advocating for the institution, yet not be as compassionate and interpersonally skilled with stakeholders. How their identities and capacities fare within their professional environments depends on contextual expectations and conditions. Such contexts can and do affect how one interprets and self-assesses their identities and capacities. Moreover, their capacities affect their identities, and vice versa. In other words, all four categorical factors are mutually influential and synergistically dependent.

The concept of a mature ego as the centerpiece of these four categorical factors indicates the importance of integrating different dimensions—intellectual, emotional, social, and moral—and mediating such integration through self-reflection and adaptive thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Those who exhibit a well-integrated ego take a step back to define what exists in situations, as perplexing and ambiguous as they are, and make decisions that acknowledge and appreciate differing perspectives. Their sensitivity to and responsiveness to their stakeholders help them to transcend and cope with conflict and disappointment and provide avenues for regrouping, always with an eye toward the institution’s well-being. They do so with an understanding of how their identities and capacities affect their decision making, and how their decision making affects their environment, which helps them to be less inclined to react, and instead, lead proactively and flexibly.

Presidents are expected to make quick and reasonable decisions while satisfying multiple constituencies. The best among them take stock of their identities and capacities to be able to self-evaluate how their decisions affect their stakeholders and adjust accordingly. When presidents possess mature egos, they intuitively know when and how to adjust their thoughts and actions within their contexts to create solutions that are mutually supportive of colleagues and the institutional context (Loevinger, 1976; Wepner, D’Onofrio, & Wilhite, 2008). If they are severely threatened by their professional environments, usually job satisfaction is compromised which can lead to exit plans. If they are in touch with how their ego is affected, and can adjust accordingly, they can help to buffer their inclination to leave prematurely.

As Travis and Price (2013) reported, more research is needed on the relationship between the preparation of presidents and their satisfaction to see whether there is a connection between the two. An important component of this research would be to investigate ways in which currently practicing presidents’ profiles contribute to or distract from job satisfaction. Analyses that use the conceptual framework as a reference could influence ways in which prospective presidents are screened for such positions.

For example, a president who is brilliant with global initiatives, yet tone deaf to internal strife, might excel at visioning, yet be incapable of truly listening to their stakeholders’ voices. While receiving high praise from the media for such bold enterprises, this leader is ignoring serious challenges that are threatening the institution’s stability. Such leadership demonstrates a disconnect between what one thinks is important and what is imperative for that context. Even with advice from the institution’s leadership, this president is exposing her lack of self-reflective and adaptive tendencies, thus perpetuating dissension which more than likely will lead to job dissatisfaction.

In sum, studying ways in which presidents’ personal identity, professional identity, and professional capacities align with the professional environment in relation to their ego development could begin to develop a portrait of critical leadership characteristics needed for success and satisfaction with the most prominent position in higher education. With turnover rates high and the pool of truly effective presidential candidates in short supply, it behooves institutions to do everything possible to retain superior leadership. In the absence of such continuity, colleges and universities are likely destined to fall short of realizing their full potential.

References

Ashmore, R. D., & Contrada, R. J. (1999). Conclusion: Self, social identity, and the analysis of social and behavioral aspects of physical health and disease. In R. J. Contrada & R. D. Ashmore (Eds.). Self, social identity, and physical health: Interdisciplinary explorations (pp. 240-255). Oxford University Press.

Bandura, A. (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 75-78.

Bornstein, R. (2003, November 14). Why college presidents don’t last. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-college-presidents-dont-last/?cid=gen_sign_in

Bowles, K. J. (2013, July 1). The president’s many roles. Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2013/07/01/many-roles-and-expectations-college-presidents-essay

Bracken, B. A., & Lamprecht, M. S. (2003). Positive self-concept: An equal opportunity construct. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 103-121.

Bruns, J. W. (2018). Presidential job satisfaction: Variables that impact satisfaction in public and private higher education institutions. Planning for Higher Education, 46(2), 81-96.

Cantor, N., & Kihlstrom, J. F. (1989). Social intelligence and cognitive assessments of personality. In R. S. Wyer, Jr., &T. K. Srull (Eds). Social intelligence and cognitive assessments of personality (pp. 1-59). Psychology Press.

Clayton, V. (2019, July 3) 7 ways the provost’s job is bigger and broader than ever before. University Business Magazine. https://universitybusiness.com/7-ways-the-provosts-job-is-bigger-and-broader-than-ever-before/

Doss Bowman, K. (2017). The erosion of presidents: Are university presidents leaving too soon? Public Purpose. https://www.aascu.org/MAP/PublicPurpose/2017/Summer/TheErosion.pdf

Duesterhaus, A. P. (2022). College presidency and university. Education for State University. Web Solutions LLC. https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2331/Presidency-College-University.html

Finkelstein, J., & Wilde, J. (2021, November 15). A fundamental change in hiring college presidents is unfolding. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/a-fundamental-change-in-hiring-college-presidents-is-unfolding/609978/

Gagliardi, J. S., Espinosa, L. L., Turk, J. M., & Taylor, M. (2017). American college president study 2017. American Council on Education. https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/American-College-President-VIII-2017.pdf

Handel, S. J. (2021). The college presidency: An interview with Brian Rosenberg. College and University, 96(4), 26-28, 30-31. http://search.proquest.com.librda.mville.edu:2048/scholarly-journals/college-presidency-interview-with-brian-rosenberg/docview/2610103005/se-2

Harris, M. S., & Ellis, M. K. (2018). Exploring involuntary presidential turnover in American higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 89(3), 294-317. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2017.1390969

Henk, W. A., Wepner, S. B., & Ali, H. S. (2021a, October). Factors academic deans consider in deciding whether to remain in their positions. The ACAD Leader, pp. 1-6. https://acad.org/newsletter_issue/current-issue/

Henk, W. A., Wepner, S., & Ali, H. (2021b, August). Why academic deans decide to stay or exit their positions. CCAS (Council of Colleges of Arts and Sciences) Update. https://www.ccas.net/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=4065-

Henk, W. A., Wepner, S. B., & Ali, H. S. (2022). Academic deans’ perceptions of factors contributing to longevity in their positions. The Journal of Higher Education Management, 37(1), 36-59.

Henk, W. A., Wepner, S. B., Lovell, S., & Melnick, S. (2017). Education deans’ beliefs about essential ways of thinking, being, and acting: A national survey. Journal of Higher Education Management, 32(1), 195-213.

Jesse, D. (2023, April 14). Portraits of the presidency: They are less experienced than ever—and eyeing the exits. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/college-presidents-are-less-experienced-than-ever-and-eyeing-the-exit?cid=gen_sign_in

Loevinger, J. (1976) Ego development: Conceptions and theories. John Wiley.

Lynch, M. (2018, January 11). What does a college president do all day? The Edvocate. https://www.theedadvocate.org/college-president-day/

MacTaggart, T. (2017). The 21st-century presidency: A call to enterprise leadership. Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges. https://www.agb. org/reports/2017/the-21st-centurypresidency-a-call-to-enterprise-leadership.

Matthews, K. K. (2021). Boards of trustees’ and senior-level administrators’ experience with presidential turnover in the higher education system: A case study (Publication No. 28644405) [Doctoral dissertation, Liberty University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

McNaughtan, J. L. (2016). Leaving so soon? Applying a fit perspective to college presidential tenure. ProQuest Central; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. http://search.proquest.com.librda.mville.edu:2048/dissertations-theses/leaving-so-soon-applying-fit-perspective-college/docview/1874874189/se-2

Mischel, W. (1973). Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review, 80, 252-253.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244, 933-938.

Monks, J. (2012). Job turnover among university presidents in the United States of America. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(2), 139-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.662739

Paterson, J. (2018, March 27). Presidents growing older, serving less time in positions. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/presidents-growing-older-serving-less-time-in-positions/519943/#:~:text=Data%20from%20a%20recent%20American,has%20dropped%20dramatically%20from%2042%25

Perrakis, A. I., Galloway, F. J., Hayes, K. K., & Robinson-Galdo K. (2011). Presidential satisfaction in higher education: An empirical study of two- and four-year institutions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(1), 57-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2011.537012

Reid, A. M. (2018). Determinants of presidential longevity in higher education: Estimating a structural model from a dataset derived from publicly available data. [Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro] ProQuest. http://search.proquest.com.librda.mville.edu:2048/dissertations-theses/determinants-presidential-longevity-higher/docview/2176559457/se-2.

Romano, C. D. (2020). Training the next generation of public college presidents: Advancing a framework to prepare aspiring college presidents. Education Database. (2451867146). ProQuest. http://search.proquest.com.librda.mville.edu:2048/dissertations-theses/training-next-generation-public-college/docview/2451867146/se-2

Rutherford, A., & Lozano, J. (2018). Top management turnover: The role of governing board structures. Public Administration Review, 78(1), 104-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12838

Schreiber, B. A. (2020, April). University president. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/job-description-of-a-university-president-2163248.

Smerek, R. E. (2013). Sensemaking and new college presidents: A conceptual study of the transition process. The Review of Higher Education, 36(3), 371-403.

Song, W., & Hartley, H. V. III. (2012). A study of presidents of independent colleges and universities. Council of Independent Colleges. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED533603.pdf

Thacker, R. S., & Freeman, S., Jr. (2020). Managing stress in a time of increased pressure: Perspectives from university presidents. The William & Mary Educational Review, 7(1), 46-70.

Travis, J. E., & Price, K. F. (2013). Preparation and job satisfaction of college and university presidents. FOCUS on Colleges, Universities & Schools, 7(1), 1-11.

Wepner, S. B., D’Onofrio, A., & Wilhite, S. C. (2004). Four dimensions of leadership in the problem-solving of education deans. Journal of Academic Leadership, 2(4), pp. 1-23. Available: http://www.academicleadership.org/cgi-bin/document.cgi?file=current/article1.dhtm

Wepner, S. B., D’Onofrio, A., & Wilhite, S. C. (2008). The leadership dimensions of education deans. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(2), 153-169.

Wepner, S. B., D’Onofrio, A., Willis, B. H., & Wilhite, S.C. (2002). Getting at the moral leadership of education deans. The Qualitative Report, 7(2). http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/Editorial/nextiss.html

Wepner, S. B., D’Onofrio, A., Willis, B., & Wilhite, S. (2003). From practice to theory: Personal perceptions of the education deanship. Academy of Education Leadership Journal, 7(2), 75-92.

Wepner, S. B., & Henk, W. A. (2020). Education deans’ perspectives on factors contributing to their longevity. Tertiary Education and Management, 26(4), 381-395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-020-09059-9

Wepner, S. B., & Henk, W. A. (2022). What might we learn from 25 Years of research on education deans? Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, 6(1), 1-21.

Wepner, S.B., Henk, W.A., & Ali, H.S. (2022, October). Factors chief academic officers consider in deciding whether to remain in their positions. The ACAD Leader, https://acad.org/resource/factors-chief-academic-officers-consider-in-deciding-whether-to-remain-in-their-positions/

Wepner, S. B., Henk, W. A., Clark Johnson, V., & Lovell, S. (2014). The importance of academic deans’ interpersonal/negotiating skills as leaders. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, DOI:10.1080/13603108.2014.963727. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13603108.2014.963727

Wepner, S. B., Henk, W., & Lovell, S. (2015). Developing deans as effective leaders for today’s changing educational landscape. Journal of Higher Education Management, 30(1), 51-64.

Wepner, S. B., Henk, W. A., Lovell, S. E., & Anderson, R. D. (2020). Education deans’ ways of thinking, being, and acting: An expanded national survey. Journal of Higher Education Management, 35(4), 15-24.

Wepner, S. B., Hopkins, D., Clark Johnson, V., & Damico, S. B. (2012). Outlasting the revolving door: Resiliency in the deanship. Journal of Higher Education Management, 27(1),1-20.

Wepner, S. B., Hopkins, D., Johnson, V. C., & Damico, S. (2011, Winter) Emerging characteristics of education deans’ collaborative leadership. Academic Leadership Online Journal, 9(1).

Wepner, S. B., Wilhite, S. C., & D’Onofrio, A. (2011). Using vignettes to search for education deans. Perspective: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 15(2), 59-68.

Wepner, S. B., Wilhite, S.C., & D’Onofrio, A. (2003, Fall). Understanding four dimensions of leadership as education dean. Action in Teacher Education, 25(3), 13-23.

Wepner, S. B., Wilhite, S. C., & D’Onofrio, A. (2002). The social and moral accountability of education deans. Action in Teacher Education, 24(1), 40-57.

Weyandt, J. (1996). Inside the college presidency. The Educational Record, 77(2-3), 6. http://search.proquest.com.librda.mville.edu:2048/trade-journals/inside-college-presidency/docview/225291566/se-2

Whitford, E. (2020, October 1). Retirement wave hits presidents amid pandemic. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/10/01/many-college-presidents-are-leaving-say-pandemic-isnt-driving-them-out

Zackal, J. (2022, April 5). Riding the wave of presidential turnover. Higher Ed Jobs. https://www.higheredjobs.com/Articles/articleDisplay.cfm?ID=3013