Stepping Down? Theorizing the Process of Returning to the Faculty After Senior Academic Leadership

Lisa Jasinski

Trinity University

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Dr. Lisa Jasinski, Special Assistant to the Vice President for Academic Affairs, Trinity University, ljasinsk@trinity.edu

Abstract

While scholars have devoted considerable attention to identifying and developing future academic leaders, scant empirical research has considered the firsthand experiences of senior leaders who returned to the faculty. This grounded theory study developed a theoretical understanding of the process of returning to the faculty after serving as a senior campus administrator. This research examined a common academic rite of passage using the analysis of interviews with 43 former college presidents, provosts, deans, and “other senior leaders” from a variety of postsecondary institutions. Academic leaders in the study characterized the process of returning to the faculty as mostly positive and liberating, prompting the need to reconsider the use of the phrase “stepping down” in this context.

In no other professional field—medicine, law, the military, business, public service, the clergy—do senior leaders habitually return to the rank-and-file workforce in the twilight of their careers. Corporate CEOs rarely conclude their working lives by resuming the duties of a mid-level account executive; on the verge of retirement, four-star generals do not return to the infantry. As a noted exception, in academia, former senior leaders, including university president, often conclude their careers by reprising the roles and responsibilities of a professor. Within the modern Academy, this professional transition is often characterized as “stepping down” and “returning to the faculty.” Beyond these well-worn clichés, little is known about how senior leaders experience these role changes firsthand. While existing studies have emphasized strategies to identify, support, and develop future leaders (Cohen & March, 1974; Gunsalus, 2006; McLaughlin, 1996; Pirjan, 2016; Smerek, 2013; Stefani, 2015; White, 2012), few consider how individuals navigate the latter phases of their academic careers, particularly moments of transition.

Moments of leadership change are so commonplace in contemporary higher education that Martin and Samels (2004) proclaimed that each year, one-fourth of all institutions “are preparing for presidential change, are in the midst of one, or have just selected a new president.” At scale, roughly 600 college presidents step down or retire each year (Andringa & Splete, 2005). According to data collected by the American Council on Education (ACE) and others, most postsecondary institutions, will experience a change in president and/or chief academic officer (CAO) approximately twice per decade, if not more often (Cook, 2012; Gagliardi, Espinosa, Turk, & Taylor, 2017; King & Gomez, 2008; Klein & Salk, 2013; Monks, 2012; Padilla et al., 2000). Although many of these leaders choose to retire outright or seek a position at another university, it is estimated one in five college presidents intends to return to the faculty (Cook, 2012). Likewise, “a significant segment of CAOs is likely to opt to retire or return to a faculty position rather than seek a presidency” (King & Gomez, 2008, p. 6). For deans and other senior and mid-level leaders, including assistant deans and special appointees, the data is too incomplete to speculate on their late-career plans. Anecdotally speaking, nary a week goes by that The Chronicle of Higher Education or Inside Higher Ed does not report on a high-profile leadership exit—either voluntarily or otherwise—at an American college or university. In a historical moment marked by continual leadership turnover in postsecondary education, these transitions take on newfound significance, urgency, and meaning.

Upon accepting their first administrative appointment, faculty members often described feelings of alienation—equating the change with “moving to the dark side” (Palm, 2006, p. 59) or “going to a new planet” (Foster, 2006, p. 49). Although former academic leaders have reflected on aspects of exiting a senior role (Carbone, 1981; Ehrenberg, 2006; Flawn, 1990; Griffith, 2006; Mallinger, 2013; Nielsen, 2013), such personal accounts are inherently anecdotal, partial, and lack theoretical heft. This study seeks to develop a theoretical model to explain the process by which senior academic leaders return to the faculty at four-year colleges and universities in the United States.

Purpose of Study and Research Question

Studies of administrators’ lived experiences remain conspicuously absent in the research about higher education leadership (Arden, 1997). Whereas the American College President Study provides a description at a population-level, rigorous qualitative studies can address the research gap by contributing nuance and offer added context. Informed by the extant literature, the results of an exploratory pilot study, and theoretical frameworks about transitions in the workplace (Dotlich et al., 2004; Fenwick, 2013), this study examined one research question from a larger study: How do senior academic leaders at four-year colleges and universities describe the process of returning to the faculty after administrative service?

Methodology

This study extended from a constructivist paradigm that contends that truth is relative, local, and specific (Creswell, 2013; Guba & Lincoln, 1998). Not unlike anthropologists, researchers operating from this epistemology “attempt to understand the complex world of lived experience from the point of view of those who live it” (Mertens, 2010, p. 16), rather than to explain objective truths. Grounded theory approaches are particularly suited to questions that aim to develop new theories or conceptual models. All grounded theory approaches are fundamentally inductive processes (Corbin & Strauss, 2007), whereby the researcher aims to move beyond description and propose a new analytic theory that is based upon actions, events, and personal experience. Because of its compatibility with my epistemological beliefs, I selected a constructivist grounded theory approach as pioneered by Charmaz (2010, 2014). A defining characteristic of this approach is that the researcher acknowledges playing an active role in developing, interpreting, and making sense of the findings.

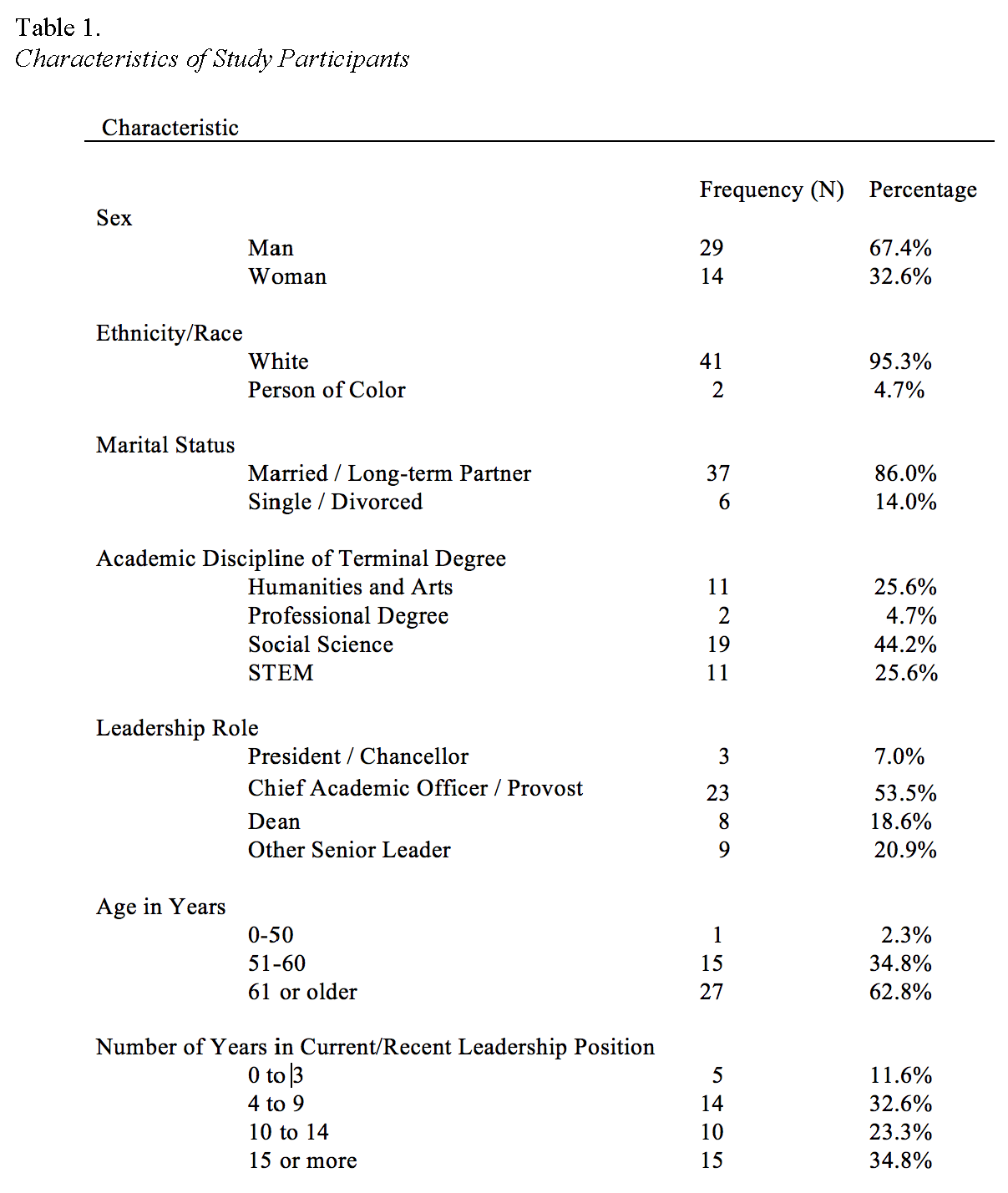

Data collection. The distinctions between data collection and analysis were intentionally blurred—both were performed simultaneously, in a back-and-forth “zigzag” process (Creswell, 2013, p. 86). Using purposeful sampling, I recruited 43 participants who: (a) are or were employed as a senior academic administrator (e.g., president, chief academic officer, dean) at a non-profit, four-year college or university in the United States, and (2) are or were in the process of returning or have returned to the faculty within the last two years. I recruited participants from across the country using referrals from my professional networks, identifying potential participants through web searches, and through snowball sampling. The large sample size (for a qualitative study) ensured that many views were considered in the development of findings and enhanced the overall trustworthiness of the study. I ceased data collection upon achieving “theoretical sufficiency”—determining that the data were robust enough to develop a theoretical model (Charmaz, 2014; see Table 1).

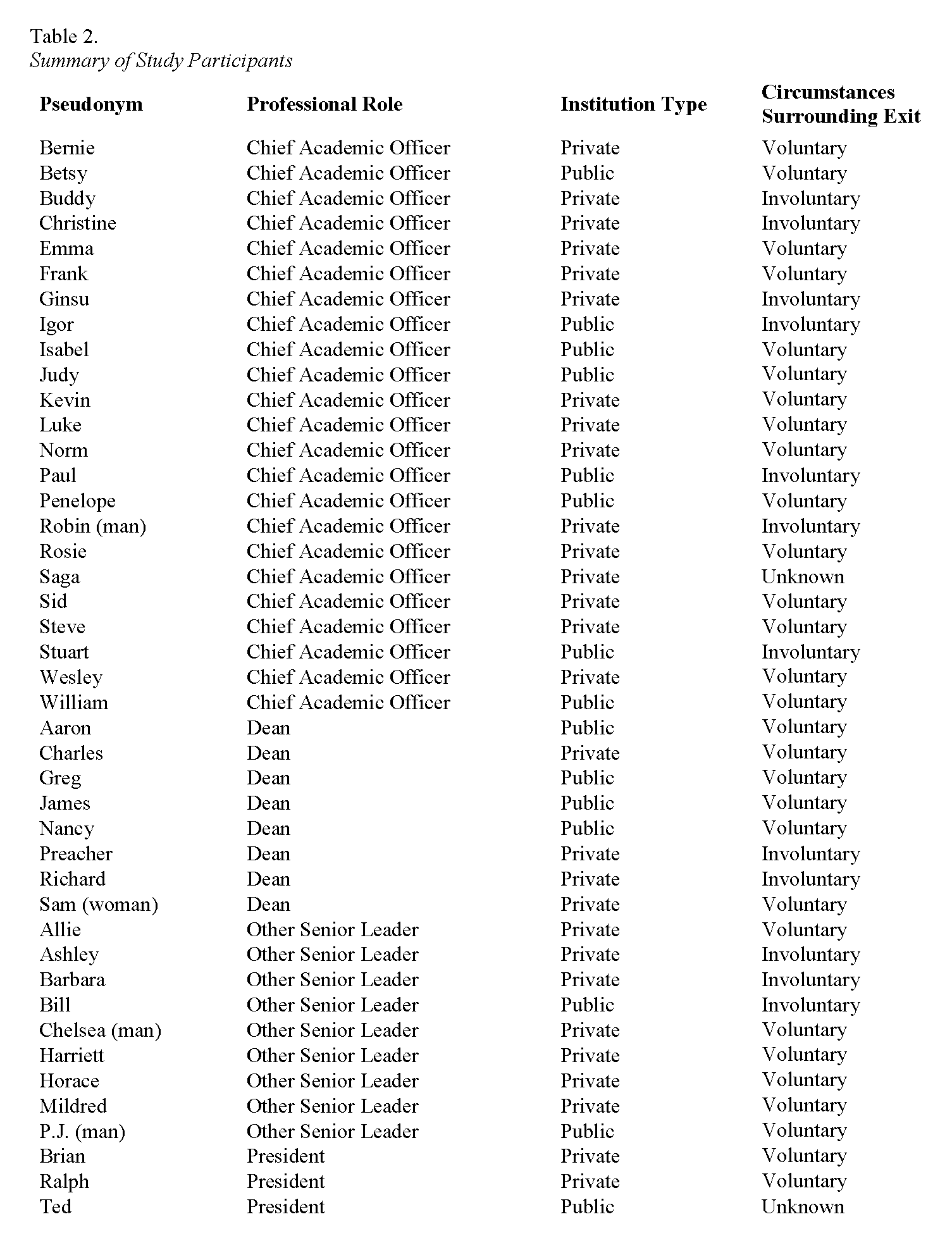

Not unlike the national population of senior administrators, men outnumbered women in the study, in this case, by a 2:1 margin. Nearly all participants identified as White. More than half of participants (n=23) served as a chief academic officer. A majority of participants (n=30) indicated that they had returned to the faculty voluntarily—they controlled, more or less, the timing of their departure or self-initiated their exit. A smaller set of participants (n=11) returned to the faculty involuntarily; even though they did not select the timing for their departure, these participants chose to return to the faculty, rather than retire or leave the institution. Participants from private institutions (n=28) outnumbered participants from public institutions (n=15) by nearly a 2:1 margin. More than half of the study’s participants were employed by a university that granted doctoral degrees (n=25); fewer participants were employed by masters (n=12) and baccalaureate (n=6) granting institutions. Most participants came from “large institutions” with a total enrollment of 10,000 or more students (n=19).

Participants were assigned a pseudonym to protect their confidentiality. Reporting additional information—such as age, length of administrative tenure, disciplinary training, race, or the size of the institution where they worked—would potentially compromise anonymity. Participant characteristics are described in the Table 2.

Verbatim interview transcripts served as the primary data source. I conducted one-on-one “intensive interviews” (Charmaz, 2014, p. 53) to explore participants’ firsthand views, assumptions, feelings, and thoughts. Between 2015 and 2019, I interviewed each participant at least once—for approximately 50 to 85 minutes—in-person, by phone, or by Skype. When possible, I conducted a second follow-up interview six months to a year later to gain a sense of the individual’s continued progression. Keeping in mind guidelines for interviewing “elites” (Dexter, 2006; Kezar, 2003), I adapted my interview protocol to acknowledge the inherent power difference between seasoned academic leaders and a novice graduate researcher. At the same time, my status as a professional higher education administrator—including extensive insider knowledge bolstered by working in a provost’s office for nearly ten years—helped establish trust and credibility.

Data analysis. Charmaz’s approach to data analysis remains characteristically more flexible than that of other grounded theorists (Corbin & Strauss, 2007; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Wertz et al., 2011). I employed a constant comparative method to identify similarities and differences across participants (Boeije, 2002; Charmaz, 2014; Wertz et al., 2011). Coding was completed in two sequential phases, initial and focused (Charmaz, 2014). Initial coding of approximately ten interview transcripts allowed me to identify a set of focused codes tailored to my research questions. Then, in the focused coding stage, I reviewed all transcripts and assigned codes that were “more selective, directed, and conceptual” (Charmaz, 2010, p. 57). Memo writing allowed me to clarify my thinking through the analysis process, to develop theoretical categories, and to explore the relationships between categories (Charmaz, 2010). Using NVivo’s™ query functions, I found that it was particularly useful to examine emergent codes—including, hanging back from campus life, feeling anxious, adopting new routine—across sub-groups in the study (i.e., chief academic officers, participants employed by a public institution, leaders who left voluntarily).

Summary of Key Findings

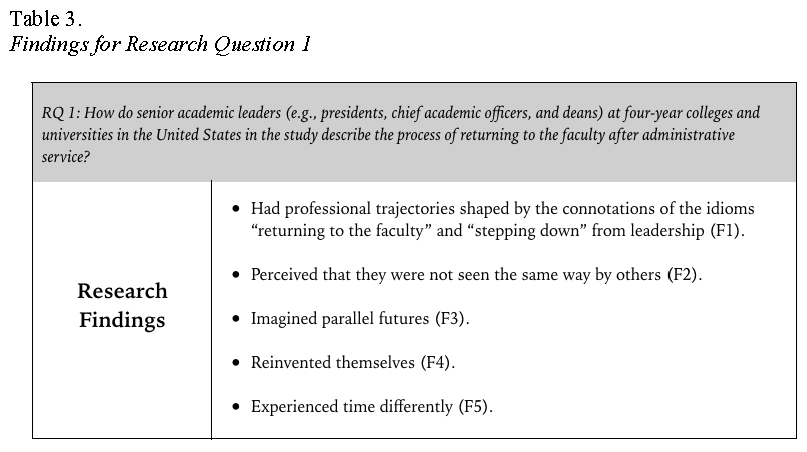

The participants in the study characterized the process of stepping down and returning to the faculty as individual, inter-related, and co-occurring microprocesses. Rather than see this professional transition as one over-arching process, returning to the faculty is marked by mutually-informing decisions, choices, and perceptions. Using inductive data analysis, I developed five thematic findings in response to the central research question. Findings are summarized in Table 3.

Finding 1: Participants’ trajectories were shaped by their understanding of the terms “returning to the faculty” and “stepping down”

Participants indicated the ways that two Ivy Tower colloquialisms “stepping down” and “returning to the faculty” at once captured some important aspects of their professional transitions while also obscuring others. For instance, some contended that the implied meanings—specifically the implication of a demotion or that they had “left” the faculty—failed to capture the most salient attributes of their role change experiences. As I argue below, even though many participants referenced these two terms, they applied different meanings to them. Participants described this process as: (a) a return; (b) a change; (c) the end of something; (d) a new beginning; and (e) a temporary placeholder. In affirming that he was returning to the faculty, Sid, a former chief academic officer at a private institution, put it this way:

So, I use the analogy of the peloton. If you follow the Tour de France or any other kind of professional cycling, you’ll know what I’m talking about. The peloton is the rider in front, he who is bracing the wind for everybody else. He can only do that for a short period of time and has to peel back in a way and return to the group. And so that was the case for me. The other reason [I’m going back] is that I’ve never lost my commitment to in-the-classroom teaching and engaging the students and my scholarship. And so the return to the faculty was really a step back into the life of the academy that first attracted me to teaching back in the beginning. It was really a cyclical move back to where I began.

By likening himself to the rider taking a turn at the front of the pack, Sid knew that it was only a matter of time until he would make “a cyclical move back” and resume the activities of teaching and research that had previously brought him fulfillment. He acknowledged that the extra energy he exerted as the metaphoric peloton left him with less time fewer reserves to engage in the traditional activities of a faculty member, including classroom teaching and research. While unable to play both the roles of peloton and pack-rider simultaneously, Sid was confident that he could occupy them successively. To tease out the deeper implications of the peloton analogy, Sid objected to the implication that he had to go back to the faculty. I suspect that he would argue that he had been there all along, serving in a specialized capacity. To demonstrate the diversity of participant opinions on this matter, take for example how former dean Nancy, she used every occasion to correct the misperception that she was retiring, saying, “I’m not retiring, I’m transitioning.” Adopting neutral language was intentional—she perceived no downsides to her impending role change. For both Sid and Nancy, we see both the limitations and resonant explanatory power of the phrases “stepping down” and “returning to the faculty.”

Finding 2: Perceiving that others see them differently

Many former leaders in the study reported that others seemed confused by their status as “former administrators.” Participants perceived that other people—faculty members, departmental colleagues, staff members, and trustees—were uncertain about how to interact with them in this new capacity. Many participants recounted exchanges in which others continued to identify and associate them with their administrative role, for instance, former chief academic officer Sid pointed out that “a lot of faculty still refer to me as dean when they speak to me—or about me to somebody else. They’ll catch themselves.” When confronted with another’s confusion, many participants described making their faculty status explicit. Upon stepping down from her role as provost at a private institution, Rosie agreed to oversee a final project that was nearing completion; although she was officially on academic leave and no longer serving in her administrative role, she occasionally participated in meetings in her capacity as project manager. Rosie explained how she dealt with this unique arrangement and the larger process of what she called “transitioning out”:

Sometimes it’s in those really finite things, like “I’m doing this, but I’m not doing that,” or “I’m not wearing the clothes I used to wear to go to this meeting,” or something like that. How do you signal to others that something is different? […] This is the transitioning out, and I can understand why that makes people uncomfortable. I think just the direct strategy is sort of what people need to hear and be continually reminded of, because for them they’re seeing it in a different way that they don’t quite understand either.

When confronting the expectations of others, Rosie took a direct approach—dressing differently, exercising strategic visibility and invisibility on campus, and calling attention to her new status to help others begin to see her anew. Rosie’s experience could be contrasted with others in the study, including Luke, Robin, and William, who opted to take a less direct route and not to speak up when confronted with others who appeared confused by their status and role.

Finding 3: Imagining parallel futures

For six study participants, stepping down from an administrative role provided an opportunity to re-think career opportunities and imagine parallel futures. This was especially true for the younger participants in the study—those in their 40s and 50s—who anticipated working for another ten to fifteen years, including Horace, Emma, Bill, and Rosie. Many of these participants weighed the merits of applying for a leadership position at another university against the familiar comforts of reprising a faculty role at their current institution. While this was a mental exercise for some ex-leaders, other participants found the act of applying for a new job to be instrumental in clarifying their professional goals. In this way, “returning to the faculty” can also be understood as choosing to remain a professor, forgoing the possibility of an administrative career elsewhere. This decision was rarely an easy one, as many participants described the complications of a mid-life career change, for instance, uprooting themselves from a known community or the employment implications for a spouse.

Bill’s departure from his appointment as an “other senior leader” at a large public university was involuntary and unexpected. The shock of his sudden dismissal was compounded by events in his personal life, including the death of a parent and his own battle with cancer. While the simultaneity of these events infused Bill’s return to the faculty with added emotional charge, the confluence of factors prompted him to step back and reflect. As part of this process, he applied for positions that were related to his previous administrative responsibilities. While he participated in on-campus interviews, the searches did not result in any offers of employment. Applying for positions was affirming and allowed Bill to exercise his personal agency:

[Applying for other jobs was] really was for my mental health to sort of see whether I was in the game, or could be in the game. And sort of whether I had choices in that regard—kind of all of that. […] But it was really important to me at the time to [apply for positions]. My wife was really stressed out about it, like “Wait a minute.” Actually, she was on board with this, but then when it came to actually possibly something happening, then it was like, “Well, I don’t know. Are we doing it?” I said, “No, no, I don’t think so.” “But then why are you doing it?” And I said, “Because I need to.”

At the risk of reading into Bill’s motivations, I think that he was compelled to exercise his personal agency because he had little control over the timing of his dismissal. The mental processes associated with applying for a new job and the act of talking about his passions and goals during a job interview helped Bill to bring a sense of closure to being forced out of his administrative position. While Bill’s job searches did not result in offers, he did not view staying at his current institution as “settling.” Instead, he reaffirmed his professional interests and recommitted to the opportunities afforded to him. Exploring options brought Bill’s goals into focus and inspired him to identify ways to “satisfy his itch” to pursue his grander ambitions to make a difference in higher education. Although Bill would have preferred continuing in his role as an “other senior leader,” he emerged from this period of reflection with added confidence and excitement about the possibilities that awaited him at his home institution as a faculty member.

Finding 4: Reinventing themselves

More than half of the academic leaders in the study portrayed themselves as becoming “new versions” of their faculty selves as a result of stepping away from their administrative duties. And while few went so far to say that they had become a wholly new person, they gave examples of how leaving a leadership role promoted the adoption of new habits, behaviors, perspectives, and conceptions of self. After completing her term as an “other senior leader,” Mildred believed that her core faculty identity persisted, though she recognized changes:

I feel like I’m a different kind of faculty member now. […] In some ways, that [leadership] experience is still with me, or it sort of informs who I am in this professor role, in a way.

Bill, the “other senior leader” referenced previously, also described himself as having become a faculty member with “new lenses.” Other participants remade themselves by launching new research programs, for instance, writing about trends in higher education or principles of leadership, or positioning themselves as public intellectuals rather than the disciplinary specialists they had once been. Participants like Harriett explained how her administrative role as a student advocate informed her teaching upon returning to the faculty. Other participants described taking on new roles at home, for example, playing a more active role in the daily lives of their children or reconnecting with their spouse. Although participants reprised the professional responsibilities they had previously held earlier in their careers like teaching and attending department meetings, they explained how they brought new perspectives, energy, and insights to their post-administrative work.

Finding 5: Experiencing and using time differently

A majority of participants (60.5%) were eager to discuss how returning to the faculty, or the prospect of returning to the faculty, altered their experience of time. Like the previous finding reinventing themselves, this was one of the most common findings from the study. Former academic leaders frequently contrasted going from a daily schedule that was highly structured and demanding to a relatively open, self-determined schedule. While participants welcomed these changes, for the most part, they recognized the need to develop coping strategies to apportion their time to serve new goals. Going on sabbatical meant a significant change from more than a decade of working as a chief academic officer: the change brought relief to Kevin’s calendar, but it also introduced new challenges. He said:

You go from that where you’re constantly driven by your calendar to having a calendar that’s entirely open. You’re back in the old faculty mode where you’re figuring out yourself what you’re going to do and what are you going accomplish today. It’s remarkably difficult to make that transition.

Although some former leaders were intimidated by the prospect of having an open calendar—especially in the immediate period following a role change—a majority of participants came to fill their newfound “free” time by engaging in activities that brought meaning and satisfaction, such as serving on a non-profit board or writing a book. Participants used words like “happier,” “healthier,” “less stressed,” and “more present” to describe themselves upon stepping down from the faculty.

Developing an Evidence-Based Framework of “Returning to the Faculty”

Examining the five findings presented above supports the proposition that “returning to the faculty” is a process marked by ambiguity, but that individuals can take steps to counteract the effects of that ambiguity. Embarking on the process of returning to the faculty creates an opportunity for an ex-leader to define the meaning of and the terms for their transitions. Ex-leaders face numerous decision-points: how to characterize the transition in their own minds, how to balance visibility and invisibility on their campuses to address perceptions of faculty peers and other university stakeholders, whether to pursue new jobs, what (if any) kind of scholarship to do and how to attend to their personal needs, and how to spend their time.

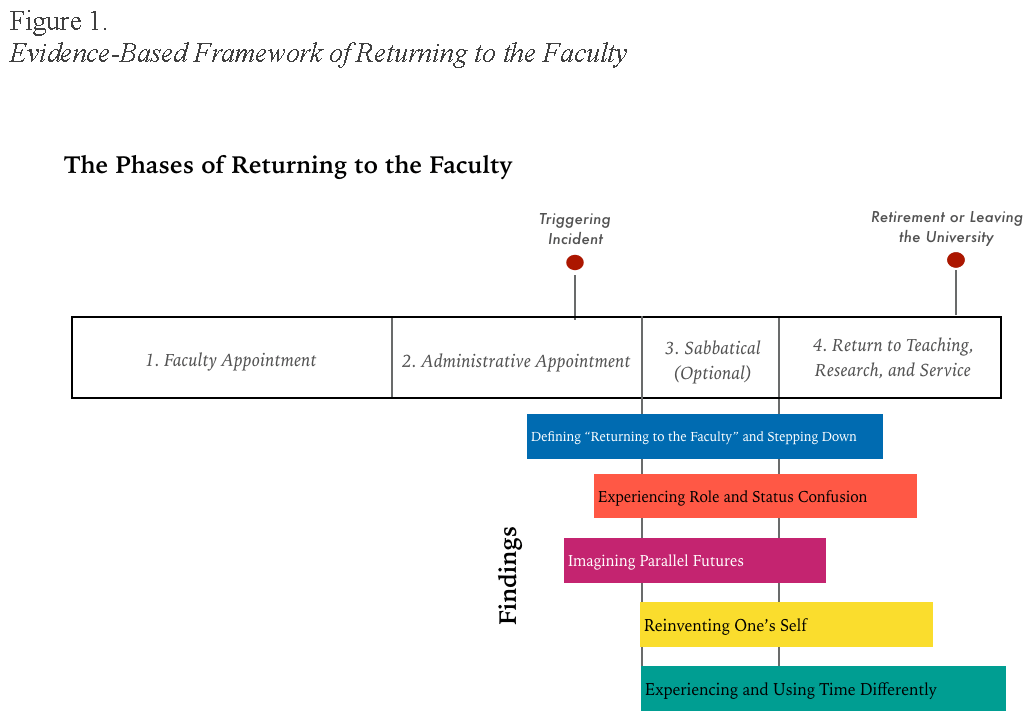

In Figure 1.1, I combined the typical chronological process of returning to the faculty with an overlay of the five thematic findings. This visual representation shows how the two ways of thinking about this process relate to one another (see Figure 1).

The rectangular box maps the typical stages in the chronological process of returning to the faculty, beginning and ending with a faculty appointment. Developing a personal understanding of what it means to return to the faculty and step down from administrative service (Finding 1) often begins or predates the incident triggering a leader’s exit. Participants’ intellectual conceptions of the process were often tested in their exchanges with others within and external to the university community. Participants often clarified for others what the process meant to them, be it a return, an ending, a new beginning, a lateral shift, or a brief interlude. Once the leader’s intention to step down was announced publically, participants began to experience status and role confusion (Finding 2); the ambiguity of their status as a former leader often continued for several years—sometimes the most profound effects occurred after returning from sabbatical or paid administrative leave. Some participants felt that their status as a former leader would remain murky for the remainder of their career, whereas participants like Mildred, an “other senior leader,” felt that the confusion subsided within three years and she had been fully accepted as a faculty peer. Upon exiting their roles, several participants in the study embarked upon their own paths of discovery—in deciding whether to return to the faculty or whether to pursue an administrative career at another institution (Finding 3). In determining which path to follow, ex-leaders found themselves weighing the relative security and comforts of their tenured faculty positions with the risk and novelty of a new position. While only a small fraction of participants (14%) imagined a parallel future—often applying for administrative positions at other institutions—for those participants who exhibited this trait, it was the most salient aspect of their return to the faculty. Deciding to stay at one’s institution or leave for another job can be an important sensemaking practice.

Study participants shared numerous examples of how returning to the faculty prompted self-invention in many aspects of their lives (Finding 4). It is important to consider how self-reinvention was not limited to professional roles—participants in the study revealed how a change in their professional role affected their familial roles or the ways they approached their physical health. Participants provided examples of how the changes began to surface during their sabbatical leaves and how self-reinvention continued upon reprising teaching, research, and service responsibilities. Across the study, self-reinvention was one of the most commonly occurring aspects of returning to the faculty—65% of participants demonstrated this finding.

A majority of former leaders (60.5%) explained that they experienced and used time differently (Finding 5). Often coinciding with the start of a sabbatical leave, participants described radical changes to their schedules. Compared to their busy administrative calendars, participants portrayed their post-administrative lives as relatively unstructured. Study participants exerted newfound control over their time in different ways, such as allocating more time to care for themselves or returning to dormant scholarly projects. In some cases, participants reevaluated their priorities in the wake of significant life events and apportioned their time accordingly.

The linear nature of Figure 1.1 falsely implies that these common experiences are distinct or only experienced sequentially. As the individual cases illustrate, participants regularly experienced these themes iteratively and concurrently (due to my limitations as a graphic designer, this model implies a rigidity that does not exist in real life). For instance, participants experienced reinvention in different sectors of their lives as distinct episodes—reinventing themselves as scholars, and then a few months later, taking on a new role at home. An unplanned interaction on campus might resurface a feeling of role confusion; even if the leader had developed a clear sense of self, periodic questions from their faculty peers about what they were working on now might prompt a backslide or a moment of doubt. In other words, it was possible for a participant to experience each of these micro-processes multiple times or concurrently. Gradually, many participants got a handle on how to use their newfound “free” time. My research confirmed that an aspect of returning to the faculty that was easy for one participant may have been debilitating for another, such as rebooting a research agenda or adjusting to playing a less visible role in the social architecture of a campus.

Conclusion

Linguist George Lakoff argued that human lives are often influenced by what he called “conceptual metaphors.” For Lakoff, metaphors shape not only how we talk, but how we think and act. As a result, he argues that we must always strive to develop better metaphors that better and more actually capture lived experiences. In the conclusion of the book, I seek to synthesize the major findings of the book while offering a critical analysis of two dominant conceptual metaphors used throughout the Academy in relation to senior administrative transitions: “stepping down” and “returning to the faculty.” For the vast majority of individuals consulted in the development of this book, neither of these terms accurately reflect their own attitudes, thought processes, or lived experiences. The 43 participants in this study believed that it was possible to return to the faculty, albeit to return as a faculty member who saw their institution and themselves through new lenses. Although some participants envisioned their return to the faculty as a brief stopover on route to retirement, others portrayed this episode as a vibrant and productive chapter in their working lives, one that in no ways was diminished by administrative service.

The development of an evidence-based framework, derived from firsthand lived experience—provides greater insight into what it means to “step down” and “return to the faculty” in contemporary American colleges and universities. Using this model, higher education practitioners, including sitting leaders who may be contemplating stepping down, can begin to structure systems, policies, and choices to better align with common findings. For instance, knowing that many campus stakeholders fail to understand the roles and responsibilities of an ex-leader (Finding 2), campuses should be more proactive in using their communication platforms. Or, knowing that former administrators may struggle with having an abrupt change in their daily schedule, it might be useful for them to consult with a peer who has stepped down previously or with a professional coach who specializes in helping individuals develop new goals and implement strategies to achieve them.

References

Andringa, R. C., & Splete, A. P. (2005). Presidential transitions in private colleges: Six integrated phases essential for success. Washington, DC: Council of Independent Colleges.

Arden, E. (1997). Is there life after administration? Academe, 83(4), 30-32. doi:10.2307/40251614

Boeije, H. R. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality & Quantity, 36(4), 391-409. doi:10.1023/A:1020909529486

Bok, D. (2002, November 22). Are huge presidential salaries bad for colleges? The Chronicle of Higher Education, 49(13), B20.

Bowen, W. G., & Tobin, E. M. (2015). Locus of authority: The evolution of faculty roles in the governance of higher education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press and ITHAKA.

Bradfield, J., Cheng, S., Clark, C., & Selingo, J. J. (2017). Pathways to the university presidency: The future of higher education leadership. Retrieved from https://dupress.deloitte.com/

Burgan, M. (2006). What ever happened to the faculty: Drift and decision in higher education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

Carbone, R. F. (1981). Presidential passages: Former college presidents reflect on the splendor and agony of their careers. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Charmaz, K. (2010). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE. (Original work published 2006)

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (Introducing qualitative methods series) (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Cohen, M. D., & March, J. G. (1974). Leadership and ambiguity: The American college president (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Cook, B. J., Nellum, C. J., & Billings, M. S. (2015). New realities and lingering stereotypes: Key trends from the national CAO census. In J. Martin & J. E. Samels (Eds.), Presidential transition in higher education: Managing leadership change (pp. 11-20). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Cyphert, F. R., & Boggs, D. L. (1986). The transition from administrator to professor: Expectations and experiences. The Review of Higher Education, 9(3), 325-333. doi:10.1353/rhe.1986.0026

Dotlich, D. L., Noel, J. L., & Walker, N. (2004). Leadership passages: The personal and professional transitions that make or break a leader. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dexter, L. A. (2006). Elite and specialized interviewing. ECPR Press: Essex, UK,

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2006). Being a quadruple threat keeps it interesting. In G. M. Bataille & B. E. Brown (Eds.), Faculty career paths: Multiple routes to academic success and satisfaction (pp. 119-122). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Ellingson, L. L. (2009). Engaging crystallization in qualitative research: An introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Esterberg, K. G., & Wooding, J. (2013). Divided conversations: Indentities, leadership, and change in public higher education. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Fenwick, T. (2013). Understanding transitions in professional practice and learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 25(6), 352-367. doi:10.1108/jwl-06-2012-0047

Flawn, P. T. (1990). A primer for university presidents: Managing the modern university. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Foster, B. L. (2006). From faculty to administrator: Like going to a new planet. New Directions for Higher Education, 2006(134), 49-57. doi:10.1002/he.216

Gagliardi, J. S., Espinosa, L. L., Turk, J. M., & Taylor, M. (2017). The American College President Study. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Gutterman, T. C. (2015). Descriptions of sampling practices within five approaches to qualitative research in education and health sciences. Forum: Qulaitative Social Research, 16(2), Art. 25. doi:10.17169/fqs-16.2.2290

Griffith, J. C. (2006). Transition from faculty to administrator and transition back to the faculty. New Directions for Higher Education, 2006(134), 67-77. doi:10.1002/he.218

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1998). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 195-220). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gunsalus, C. K. (2006). The college administrator’s survival guide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kezar, A. (2003). Transformational elite interviews: Principles and problems. Qualitative Inquiry, 9(3), 395-415. doi:10.1177/1077800403251762

King, J. E., & Gomez, G. G. (2008). On the pathway to the presidency: Characteristics of higher education’s senior leadership. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Klein, M. F., & Salk, R. J. (2013). Presidential succession planning: A qualitative study in private higher education. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(3), 335-345. doi:10.1177/1548051813483836

Luna, G., & Medina, C. (2006, Summer). Coming full circle: Mid-career women leaving administration and returning to faculty. Advancing Women in Leadership, 21. Retrieved from http://www.advancingwomen.com

McLaughlin, J. B. (Ed.) (1996). Leadership transitions: The new college president (Vol. 93). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mallinger, M. (2013). Faculty to administration and back again: I’m a stranger here myself. Journal of Management Inquiry, 22(1), 59-67. doi:10.1177/1056492612461950

Martin, J., & Samels, J. E. (Eds.). (2004). Presidential transition in higher education: Managing leadership change. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mertens, D. M. (2010). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Monks, J. (2012). Job turnover among university presidents in the United States of America. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(2), 139-152. doi:10.1080/1360080x.2012.662739

Nielsen, L. A. (2013). Provost: Experiences, reflections and advice from a former “number two” on campus. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Padilla, A., Ghosh, S., Fisher, J. L., Wilson, B. J., & Thornton, J. S. (2000). Turnover at the top: The revolving door of the academic presidency. Presidency, 3(1), 30-37. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ615002

Palm, R. (2006). Perspectives from the dark side: The career transition from faculty to administrator. New Directions for Higher Education, 2006(134), 59-65. doi:10.1002/he.217

Pirjan, S. S. (2016). Making history and overcoming challenges: The career pathways and career advancement of female provosts in the Califoria State University system (Doctoral dissertation). Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 10141722)

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: Markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Smerek, R. E. (2013). Sensemaking and new college presidents: A conceptual study of the transition process. The Review of Higher Education, 36(3), 371-403. doi:10.1353/rhe.2013.0028

Spalding, N. J., & Phillips, T. (2007). Exploring the use of vignettes: From validity to trustworthiness. Qualitative Health Research, 17(7), 954-962. doi:10.1177/1049732307306187

Stefani, L. (2015). Stepping up to leadership in higher education. All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 7(1), 2161-21618. Retrieved from http://ojs.aishe.org/

Wertz, F. J., Charmaz, K., McMullen, L. M., Josselson, R., Anderson, R., & McSpadden, E. (2011). Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: Phenomenologcial psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research, and intuitive inquiry. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Wexler, E. (2016, April 6). Law school co-deans: ‘Like a marriage.’ Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://insidehighered.com

White, G. (2012). Faculty transitioning into associate dean positions in higher education: Perspectives on personal and professional experiences (Doctoral dissertation). Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 550424)

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 2. Summary of Study Participants

Table 3. Findings for Research Question 1

Figure 1. Evidence-Based Framework of Returning to the Faculty