Liaison, Delegates, and Advisors: An Examination of the Chief of Staff Role on College Campuses

Laura Jacobs

University of Arkansas

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Laura Jacobs, Chief of Staff, University of Arkansas, laurahjacobs@gmail.com

Abstract

The chief of staff role first emerged as a military and government position to strategize battles and advise generals centuries ago (O’Brien, 2020). It has been more common in the United States to find chiefs of staff (or COS) in political environments: The White House chief of staff often comes to mind when the title is mentioned. In recent years the role has been adopted by corporate entities. Companies often create and hire individuals into the title to organize senior level, institution work (Ciampa, 2020) and the corporatization and resulting organizational changes in higher education (Bleikliea & Kogan, 2007) have led to the adoption of the COS role by college presidents as well. Following discussions with, and the review of credentials of, nine incumbent chiefs of staff and a review of position descriptions of a handful of others, some trends emerged and are reported here.

The chief of staff role first emerged as a position in military and government applications to strategize battles and advise generals centuries ago; in recent years it has taken on a more corporate focus with more companies creating and hiring positions with this title (Ciampa, 2020). It has been more common in the United States to find chiefs of staff (or COS) in political environments: The White House chief of staff often comes to mind when the title is mentioned.

The COS role is decidedly different from that of the leader’s executive assistant (EA). Unlike an EA, a chief of staff works autonomously and does not handle routine correspondence or manage the leader’s day-to-day schedule. The highest-level CoS should be a full-fledged member of the senior leadership team, albeit without the rank or compensation of a C-suite officer (Ciampa, 2020, ¶6).

Only within the past decade has the COS position emerged fully by this title on the college campus. Institutions may have held aid positions or other advisory, or liaison positions, but these roles were often titled as “special assistant to the president” or “liaison to the president,” or even “executive assistant.”

Following discussions with, and the review of credentials of, nine incumbent chiefs of staff and a review of position descriptions of a handful of others, some trends have emerged and are the focus of the current discussion.

Literature Review

The historical presence of a chief of staff position emerged from military contexts and was adopted by presidents of the United States, often tapping military admirals or generals to serve in the role (O’Brien, 2020.) The presidential use of the COS has been a near-regular presence in American politics since the Nixon administration and studied almost as long to better understand the scope and duties of the position and the characteristics of incumbents (Walcott, Warshaw, & Wayne, 2001). Lessons learned over time suggest that the position should be considered essential, but that the temperament of the COS is equally essential to aid in decision-making and avoid problems (Pfiffner, 1993). The description of the position as an advisor to the head of state and be allowed access to privileged and sensitive information provides a blueprint to aid in understanding the scope of the role: “The chief of staff was to be Roosevelt’s most senior military advisor, a regular presence in his professional and personal life. He and Leahy would meet daily to discuss both the crucial issues of the moment and the larger strategic questions for the future (p. 179).”

The need to have a “right-hand” to aid the chief executive of a company is another important parallel from which academia has drawn much influence for organizational and operational strategy and tactic. The purpose of a COS has been described as a critical position to help with time management through the allocation of high-level tasks and projects enabling the chief executive to free their time for other activities. The value of having someone other than an executive assistant to help make the senior most leader make the most strategic use of limited time for decision-making and implementing policies cannot be overstated (Ciampa, 2020).

The evolution of the COS role in higher education settings has been less easy to pinpoint, but evidence and review of presidential leadership practice and effectiveness has yielded some reasonable conclusions. Shepherd’s (2018) analysis of leadership size and structures in pre- and post-1992 higher education institutions in the UK revealed the convergence of models that are designed to strengthen the university executive. Concepts such as the development of executive teams as the next tier below the president emerged as a way to make institutional governance and operations more business-like and new “vice” or “deputy” positions were created to spread the responsibility of executive roles to other leaders (Shepherd, 2018). These positions increased by 55% in a decade, and while the growth of a position titled “chief of staff” is not expressly cited, the demonstrated growth of “next tier” leaders such as vice presidents and the emergence of executive teams signals diversifying support for the chief executive while moving higher education closer to corporate administrative structures.

Although leadership is generally seen as distributed throughout institutions in this more corporate or entrepreneurial structure, there is wisdom in deliberate development of individual leaders’ networks and networking for the purposes of leveraging influence useful for developing consensus (Bolden, 2008). Internationally, there has been a movement in higher education toward the campus leader to trend toward running a “corporate institution” (Bleikliea & Kogan, 2007, p. 20) resulting in presidents looking more like CEOs, and institutions looking more standardized organizationally.

Building trust and relationships with both internal and external constituencies is essential for a COS who can often serve as a confidant for the chief executive (Finding Your Feet as Chief of Staff, 2019). The necessity of, and correlation between, building internal and external relationships is not only an important corporate (or institutional) function to attain consensus and championship, but a public relations imperative (Cardwell, Williams, & Pyle, 2017). Often, these position descriptions are written in such a way to emphasize strategic problem-solving and an ability to coalesce influencing responsibilities (University of New Mexico, 2020). The role is sometimes defined as for someone who is “politically astute, with a high level of emotional intelligence, sound judgement, and a commitment to helping a team succeed” (University of Texas at San Antonio, 2020).

The literature regarding the genesis of these positions in higher education is severely limited, but in talking to individuals holding the COS title at various institutions in the southeast part of the US, there is a history at their institutions of having such a role.

Interview Protocol and Experience

I first sought to generate a roster of current and former COS professionals at Southeastern Conference institutions using an online search of institutions and titles and confirming with campus directories, adding the names and contacts of other individuals serving in the role at various four-year institutions in the US. The sample yielded a population of 16 individuals, and 9 were selected for inclusion in the study. One appointment was cancelled and not able to be rescheduled in time for the study’s completion. The use of a sample of 8 was based on qualitative research precedence and not focusing on a particular number of interviews, but rather, a predetermined initial set of interviews to be completed with data analysis until response patterns are repeated (saturation).

An initial email was sent to all the contacts to introduce myself and request a short appointment to communicate the twofold purpose of making a connection for networking and information-sharing purposes, and second, for gathering data relevant to the current study. I arranged for telephone meetings or the opportunity for a chief of staff to respond to a series of questions/discussion prompts delivered electronically. Areas of questions and discussion included:

- Background credentials

- How did you get into the role?

- What is in your portfolio?

- Do you feel your tenure is tied to that of your bosses?

- What comes next?

All conversation requests were accepted and completed over the telephone during the Fall 2020 semester. As a note, the rise of the COVID pandemic provided initial areas for discussion and strategy sharing, and the heightened severity of COVID did provide a background for developing trust and open communication with each COS professional.

Trends and Themes

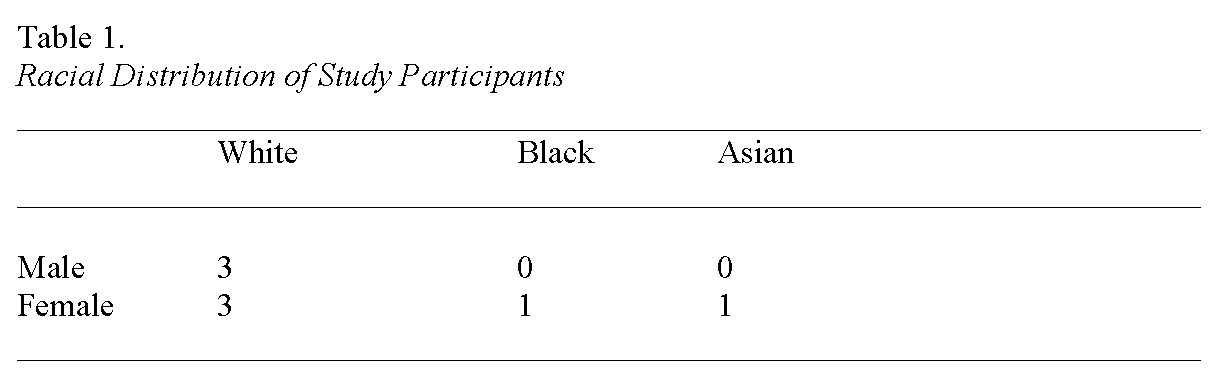

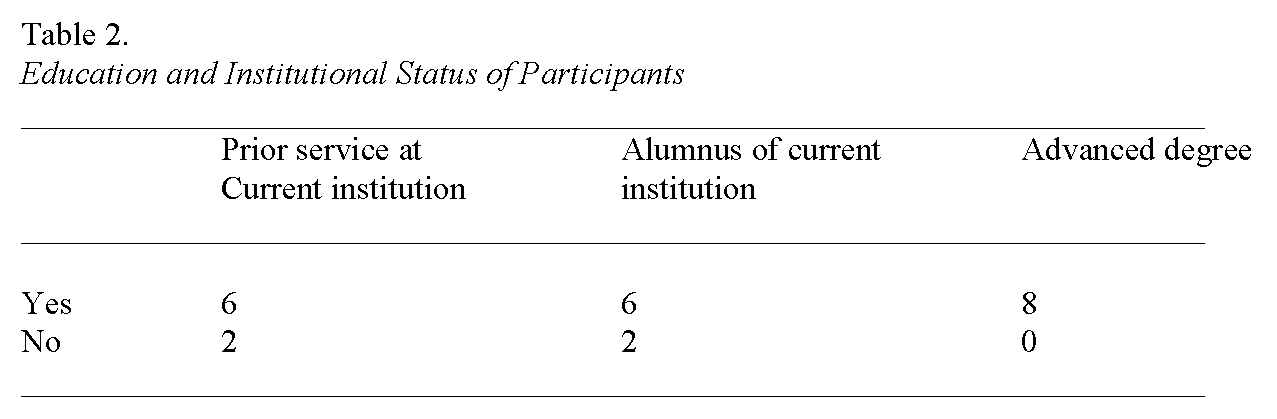

All of the incumbents were appointed to their role with the hire of new presidential leadership at predominantly public institutions. Six were alumni of the institution and all held graduate or professional degrees in the fields of literature, business, communications, education, or law. Seven had served the institution in another capacity prior to being hired as the COS. Half had a role on the search committee that led to the hire of the new president and the others were involved in some way in the transition of onboarding the new president. Three had Title IX or other compliance or diversity, equity and inclusion responsibilities in their portfolio of work responsibility. All had responsibilities for coordinating and day-to-day liaising with the “cabinet” or senior leadership on the campus. Professionally, the backgrounds of the COSs interviewed spanned from legal/general counsel positions on campus or government relations, and communications roles, with each of those positions being the immediate past role prior to hire as COS. One exception was a COS who had held an academic position at the institution. All perceived that their tenure was tied to that of their boss, meaning a likelihood of the end of their service as COS when the president steps down or moves to another institution. A lone COS had been recruited to the new institution with the new president, having served in the same role for that individual elsewhere; this example was an outlier.

Adding to their professional portfolios, the responsibilities ranged from policy and government relations, compliance oversight, crisis management, COVID response leadership, budgetary management, and an ubiquitous category of “management of special projects.” The latter being a catch-all for advancing the president’s agenda through assigning and assembling teams and task forces or managing such projects on individually. As mentioned, all of them had responsibility in coordinating the cabinet meetings as well as serving as a day-to-day liaison with the cabinet members, typically the vice presidents/chancellors, to provide guidance, to help move initiatives along, as well as to digest information to present to the president as a time-management tool.

“Whatever needs to be done to help the chancellor use her time to do what she needs,” said one COS. In addition to helping the president manage time, most COSs also viewed their roles as helping members of the cabinet use their time efficiently as well: “My job is helping them to do their jobs. I can help put things on their radar to help them do their job well,” through bringing up issues and items that may be on the president’s mind to help cabinet members avoid surprises or pitfalls.

The vast, but difficult to describe, scope of the COS role was often cited as well. Several individuals described “giant portfolios,” and one described a function of ensuring that “everything going to the president has been ‘baked’ all the way… Wringing it out to make sure it’s ready for prime time.” When reflecting on how they explain their job to others, one COS said “it doesn’t make sense, or sound like a real job, to people who don’t do it.”

One former COS now presides over a consortium of community colleges in his state, having leveraged his experiences and contacts in the COS role to position his move almost simultaneously with the departure of the university president. “I was relieved of my duties when the new chancellor was hired and came in wanting to build his own team,” he said, noting this fact was viewed not with surprise, but rather with an expectancy.

During the time this article was written, one university announced a major institutional restructuring that resulted in the elimination of the COS position. This was not insignificant in that the announcement of the elimination indicated the institution would be “spreading out that authority among those who will directly report to me [the president],” and will be interesting to follow this development to how well it works.

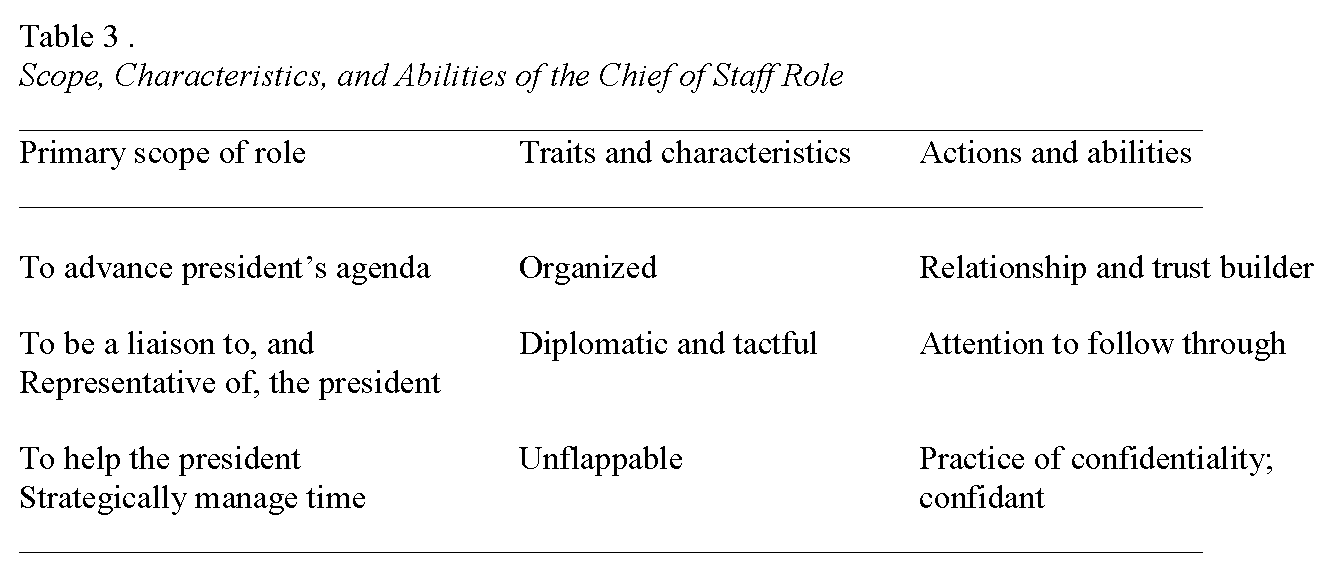

There are a set of qualities, knowledge, skills, and abilities that appear to characterize the qualities of successful COSs, as defined by the study participants. The ability to work with people, a sense for diplomacy, flexibility and a lack of being “easily ruffled,” as well as a relentless practice of diligent organizational skills, follow up and follow through were the common threads cited by the interview subjects. “The ability to keep running into a brick wall and get things done behind the scenes,” or “tenacity” was how one COS described his greatest strength.

Building on the theme of personal demeanor, COSs must be unexcitable, also called unflappable, unperturbable, yet self-motivated. Various synonyms for “calm,” were presented throughout the interviews as a necessity of the job. “I’m the steady influence in any meeting,” said another, noting the balance between being active and proactive. “I can’t be passive.”

Consensus building, sometimes referred to as the ability to attain “buy in” for projects, programs, and concepts, is another theme of the job. “I believe in management by walking around,” meaning one COS actively seeks other people on campus, making unscheduled visits but mostly taking advantage of the serendipitous interactions that may result in discovering unexpected data or creating an opportunity to answer questions and deliver information that helps achieve a shared understanding of a project or priority of the president.

The theme of the loneliness of the role emerged as well during the interviews. For these institutions, there was typically one COS at the institution who was often charged to help advance change and administer priorities and projects that may not be popular. “You need to be your own island,” one observed, as well as the ability “to say no forcefully but in a way that keeps people coming back to you.” In terms of collegial opportunities, “I don’t participate in professional development,” cited one COS, commenting that there are parallel professional opportunities for SEC provosts, communications officers, deans, and other positions to network, convene, and share best practices. Often, the COS has to deliver bad news or decisions from campus leadership, sometimes earning them a reputation for being authoritative, a bearer of bad news, or even heavy-handed. “I don’t need to be liked,” said one COS about her colleagues and coworkers as one who is often called into to “clean up” underperforming units. “I am respected, however, and have a reputation for delivering.”

Conclusions and Implications

Among the self-identified traits of COSs and related to the scope of their role, they tend to be organized, diplomatic and tactful, and possess a quality often characterized as “unflappable.” They must be able to act as a relationship and trust builder, have a keen ability to follow through and encourage like behavior in others, and be highly attuned to handling sensitive and confidential material and matters. The ground zero of trust building lies in building a solid relationship with the president. One COS told the story of her hiring into the role and the intentionality with which she sought to build a connection to the president through personal storytelling. “We got to know each other first through who we were as people, spending time together outside of the office having conversations,” she recalled, citing this as the single most important activity to kick off their mutual tenures. “The president has a tremendous amount of trust in me,” she continued. These positions are essential on college campuses primarily due to the nature of the enormous workload and pressing demands and responsibilities of the president. The president cannot be everywhere at once so having a trusted representative or liaison is necessary. Nor do they have time to review and disseminate voluminous information and the duties of the COS to help gather, synthesize, and filter the essence of the important information back-and-forth between the president and various constituents is a primary function of the role.

People aspiring to the role may be well served through professional roles in strategic communications, public relations, brand management, governmental relations, or general counsel in higher education settings. Reviewing position descriptions can be a helpful tool for confirming and then building the desired knowledge, skills, and abilities sought for the campus COS. Correlated to individual aspiration is the conclusion that institutions should carefully select search committee members for future presidential searches given the prevalence of those members ending up in COS roles, and future college and university presidents could potentially view members of the search committee as a pool of prospective COSs.

Finally, there must be an acknowledgement of the inherent public relations function of the COS role and the importance of this to the overall need for the institution (and the president) to build and maintain relationships with internal and external stakeholders. The COS plays a valuable presidential support role in this regard, which ultimately assists the institution.

The fact that one institution has recently downsized their cabinet and eliminated a formal COS role does not necessarily signal a trend, but is something to watch given higher education’s tendency to look toward other institutions for ideas and organizational practices and the institutional need to tighten finances in the current pandemic. Even so, given presidential need and the utility of these unique roles, most signs point to a continuation of this role on college campuses.

References

Bleikliea, I. & Koganb, M. (2007). Organization and governance of universities. Higher Education Policy, 20(4), 477-493.

Cardwell, L. A., Williams, S., & Pyle, A. (2017). Corporate public relations dynamics: Internal vs. external stakeholders and the role of the practitioner. Public Relations Review, 43(1), 152-162.

Ciampa, D. (2020, May/June). The case for a chief of staff. Harvard Business Review. Available online at https://www.academicimpressions.com/blog/chief-of-staff-first-day-on-job/

Bolden, R., Petrov, G., & Gosling, J. (2008). Developing collective leadership in higher education. Final report. London, England: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

“Finding your feet as chief of staff.” (2019). Academic Impressions. Retrieved from https://www.academicimpressions.com/blog/getting-started-chief-of-staff/

Pfiffner, J. P. (1993). The president’s chief of staff: Lessons learned. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 77-102. “Position classification description.” (2020). University of New Mexico, chief of staff, president’s office. Retrieved from https://jobdescriptions.unm.edu/detail.php?v&id=A9000#:~:text=The%20Chief%20of%20Staff%20is,and%20community%20and%20government%20leaders

“Position description for the position of chief of staff at the University of Texas at San Antonio.” (2020). Diversified Search Inc.

Seltzer, R. (2017.) The slowly diversifying presidency. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/06/20/college-presidents-diversifying-slowly-and-growing-older-study-finds#:~:text=The%20average%20tenure%20of%20a,in%20five%20years%20or%20sooner

Shepherd, S. (2018). Strengthening the university executive: The expanding roles and remit of deputy and pro-vice-chancellors. Higher Education Quarterly, 72(1), 40-50.

Walcott, C. E., Warshaw, S. A., & Wayne, S. J. (2001). The chief of staff. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 31(3), 464-489.

Table 1. Racial Distribution of Study Participants

Table 2. Education and Institutional Status of Participants

Table 3 . Scope, Characteristics, and Abilities of the Chief of Staff Role