Faculty Senates and College Presidents: Perspectives on Collaboration

Daniel P. Nadler

Northern Kentucky University

Michael T. Miller

University of Arkansas

Eid Abo Hamza

Qatar University

G. David Gearhart

University of Arkansas

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Dr. Daniel P. Nadler, Vice President for Student Affairs, Northern Kentucky University, Highland Heights, Kentucky, USA, nadler@nku.edu

Abstract

Colleges and universities have historically provided faculty members access to sharing authority, and this has been manifest in recent decades through the creation and use of a formal body called a faculty senate. These formal bodies have at times been highly effective at articulating faculty member interests, yet there are few formal definitions or boundaries concerning what areas senates are most appropriately engaged. College presidents similarly recognize that senates have a role in institutional decision-making, yet often lack a clear understanding of where and how they should be engaged. The current study explored faculty senate leader and college president perceptions of boundaries of senate collaboration in decision-making. Survey respondents identified a high level of agreement that faculty senates should be engaged in academic collaboration with the president, but there was less agreement concerning collaboration in areas of campus life and work-life.

Shared governance is both a hallmark of American higher education and an organizational performance strategy (Rosser, 2003). Through the collaboration and involvement of different internal stakeholders, college presidents can build enough consensus to advance agendas, gather input for a collective vision, and focus an institution’s human resources to maximize performance. From an historical perspective, shared governance has such a strong historical underpinning that virtually all of the institutional regional accrediting bodies require some demonstration of shared governance. Despite this, the concept of shared governance and in turn, shared decision-making, has struggled (Birnbaum, 2004).

Despite the importance placed on shared governance, evidence of its effectiveness is sporadic at best (Schoorman, 2018). Multiple studies have identified moderate to poor attendance at faculty senate meetings (Miller, Williams, & Garavalia, 2003), a frequent inability to influence “big” decisions (Sibley, 1998; Waugh, 2003), and often an emphasis on issues that are not considered by other governance units on campus (Miller & Nadler, 2019, in press). A dissenting notion of the faculty governance unit, however, is that it is intended to give voice to the institution’s faculty, not necessarily to make or influence decisions (Miller, 1999). Additionally, shared governance units can function in a highly situational manner, where its work is critical in one year, and might be less impactful for many years after that particular instance.

Reliance on faculty governance for decision-making is often assigned to a provost or president, depending upon how the governance unit is structured. In situations where the unit is designed to expressly deal with curricular matters, these units are most likely assigned to the academic vice president (provost). The majority of governance units, however, frequently and commonly referred to as “senates,” deal with a broad array of issues and matters, and have interests that cross all aspects of an institution’s leadership (Gilmour, 1991). Additionally, college presidents frequently see such senates as the representation of the faculty’s collective voice, making these bodies greatly important.

Faculty senates vary in structure and in their ability to be responsive to different ideas or agenda items. Some senates offer apportionment based on student enrollment or faculty size, and others have restricted numbers of representatives with an equal number coming from different parts of the campus. The majority of faculty senates are based on academic colleges, working from the assumption that faculty members in a particular academic discipline have some shared set of experiences, values, and concerns that are best vocalized through a distinct delegation. Some smaller institutions, however, have broad-based elections that are purely driven by candidate statements of interest and have no relationship to academic segregation. As with other research on faculty governance units, there is little to indicate which type of apportionment model is best for representing faculty interests.

Ultimately, some research has suggested that the motivation and leadership skills of a faculty senate leader is what determines the success or failure of a senate’s work (Miller, 2003; Johnston, 2003). Similarly, the investment of central administration in recognizing the legitimacy and relevance of a faculty senate’s work is key to the acceptance and value of a senate’s decision making. Therefore, the purpose for conducting the study was to identify how faculty senate leaders and college presidents perceived best practices for shared governance collaboration.

Background of the Study

Over 30 years ago, Robert Birnbaum (1989) described higher education decision-making as ‘coupling,’ using a manufacturing term to reflect the cause-effect relationship of decisions in the academy. Birnbaum profiled five different types of classifications of higher education institutions, noting that in at least one model (bureaucratic) there was a very tight ‘coupling’ between administrative decisions and the implementation of these decisions. For example, if the president of an institution issued a decision to eliminate tobacco use on campus, the decision would be accepted and implemented with little rebuttal. In a loosely coupled environment, however, the campus’ administration might issue a decision that is only marginally accepted and implemented by some. An example of this might be a decision that all faculty and staff should wear school colored clothing on a particular day of the week, and in implementation, few actually would.

Decision-making in an organizational behavior context has a great deal to do with this concept of ‘coupling,’ but in human resource rich environments, such decision implementation action is predicated on the relationships between individuals in the organization. In simple terms, if employees are given access to decision-making and input to agenda items to be considered, they are more likely to have faith in the administration in making decisions about them and are more likely to accept and implement them. This process of input and employee commitment to an institution are also manifest in the concept of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), where high levels of OCB have been correlated with multiple organizational benefits such as higher morale, less intention to leave, and commitment to organizational goals (Rose, 2012).

Shared decision-making between faculty and administration has not consistently demonstrated the same benefits as it has in the private sector. In many cases, faculty governance units have positioned themselves in opposition to central administration or leadership, believing their role is to serve as check-and-balance to the administrative leadership of an institution. This might be to challenge perspectives and ideas of how best to work with students, how to structure a campus’ academic offerings, and where to prioritize budgetary commitments. Shared governance in the academy has not consistently impacted ‘big decisions’ on campus, and the topics undertaken between faculty and other constituent groups on campus tend to be incongruent (Miller & Nadler, 2019).

A potential problem that shared governance units, like faculty senates, face is that they often lack clarity or an ability to articulate why they exist and how they can fulfill their mission. More than simply defining outcome statements or a vision or mission statement, these bodies often are composed of so many different individuals with different ideas, the organizations are impaired in their ability to make meaningful change. Part of this difficulty in establishing a mission was explained by Miller (1999) who argued that organizations like faculty senates need to spend time negotiating what it is they are truly designed to do before they spend significant time establishing an agenda or launching into a new year’s worth of work. He outlined several possible structures for faculty senates, ranging from their involvement simply to placate faculty concerns to fully sharing in authority and power. For this to be effective, though, he argued that there must be clear dialogue between those with legal authority for an institution and the governance body; the group that holds formal power must be willing to articulate what it is that they are willing to share with faculty members in making decisions.

The ability of shared governance units to effectively function is made even more complex through the individual interpretations of what issues are most important to campus, how they might be approached or solved, and their own internal competition and congruence of thinking. In one such setting, observations of a faculty senate identified in-fighting, political posturing, and all of the behaviors that might be seen in a state or federal legislative body (Miller, Williams, & Garavalia, 2003). The result of all of this behavior and complexity is that for college presidents, it is often simply easier and more efficient to place little value on the faculty governance unit and to rely on smaller groups of faculty for input. In some instances, this means that the college president simply meets with executive leaders from a shared governance body and considers this representation to be the official voice of the faculty. In these settings, a small elite group of faculty are granted access to the power base of an institution and can potentially impact change. The difficulty in exploring the use of elite groups in decision making, however, is that they can often describe their own perceptions and biases and might be ill-equipped to verbalize those voices from whom they were elected. Additionally, the behaviors of elites in decision making can lead to a lack of transparency and selectivity in information sharing.

Small groups of faculty who have input into the decision-making process can also serve as filter to the topics that a faculty senate addresses. Armstrong (1999) provided one case study exploration of faculty senate topics and found a wide range of areas in which the senate worked. These ranged from compensation and human resource benefits to symbolic cultural elements of campus, such as which flag is flown over the administration building. In Armstrong’s case, the senate served to set an agenda for the entire campus’ faculty.

Because of the need to define the role of faculty governance bodies, and due to the temptations associated with creating elite sub-structures in the governance process, the current study was designed to look at how these two groups, faculty members and presidents, perceive themselves to be working together.

Research Procedures

As an exploratory study, a random sample of 100 faculty senate presidents and 100 college presidents were selected from a commercially produced directory of approximately 1,359 colleges and universities. The population of four-year universities was first limited to comprehensive and doctoral universities, and then using a table of random numbers and a random number assigner program, this listing of comprehensive and doctoral universities was sampled to produce 200 institutions. The first 100 of these institutions were then manually searched online to develop a listing of faculty senate presidents and the second 100 institutions were manually searched to identify contact information for college presidents.

Data were then collected from the samples using an 18-item, research-team developed survey instrument. The instrument was based on existing literature about what faculty governance units typically do and what kinds of issues they undertake. The survey contained a qualifying question to assure that the survey was being completed by one of the two target-sample individuals, and then included six items on academic collaboration, six items on campus life, and six items on work-place life. Each item requested that sample participants rate their perceived level of agreement on a 1-to-5 Likert-type scale that each item was an important area for presidential and faculty senate collaboration. The scale made use of a progressive scale, where 1=Strong Disagreement, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither Agree/Disagree, 4=Agree, and 5=Strong Agreement.

The survey instrument was developed and delivered electronically, and went through four different iterations based on feedback from non-participating presidents and faculty senate leaders. The survey, following multiple revisions, was sent to a non-participating sample of 15 presidents and 15 faculty senate leaders to determine length of time needed to complete the survey. In this administration of the instrument, a Cronbach alpha was computed at .6233, which was deemed to be acceptable in establishing the reliability of the instrument.

Findings

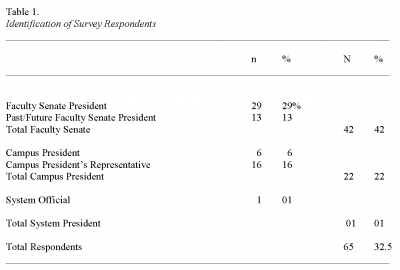

A total of 65 usable surveys were returned followıng three remınder notıces to the email dıstrıbutıon of the survey. As shown in Table 1, 42 of the surveys were returned from the sample of 100 faculty senate leaders and 22 were returned from the sample of 100 college presıdents. Also shown ın Table 1, however, ıs the distribution of who completed the survey, ıncludıng 29 current faculty senate presıdents and 13 future of former faculty senate presidents. Sımılarly, 6 of the surveys were completed by ındıvıduals who reported servıng ın the college presıdent’s role, and 16 were completed by a representatıve of the president. Addıtıonally, one survey was returned from an ındıvıdual who reported beıng from a unıversıty system level offıce.

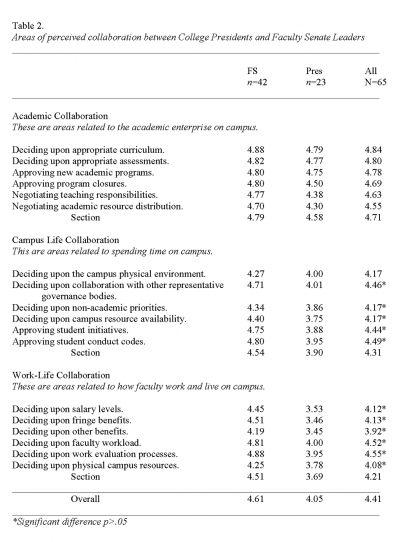

The first section of the survey included six statements about the faculty senate and college president and academic collaboration. These statements all related to the academic enterprise of the campus. Faculty senate leaders agreed most strongly with the statement of the faculty senate plays a key role in deciding upon appropriate curriculum (x̅=4.88), decidıng upon appropriate assessments (x̅=4.82), and approving new academic programs (x̅=4.80), and academic program closures (x̅=4.80). The responding presidents agreed most strongly with the same items, although with a lower level of agreement for each item (x̅=4.79, x̅=4.77, x̅=4.75, x̅=4.50, respectively).

The second section of the survey ıncluded six statements about campus life collaborations and faculty senate leaders had an overall mean rating of agreement with these items being areas of collaboration at 4.54, meaning that they agreed to strongly agreed that the campus life elements were areas that faculty senates and presidents should collaborate. The responding presidents, however, had an overall mean rating of 3.90, and an Analysis of Variance, one-way, indicated that these mean ratings were significantly different (p>.05), and post hoc Tukey pairwise comparison identified that five of the six mean ratings were significantly different. Similarly, the one-way ANOVA conducted on the six items in the Work-Life Collaboration category were found to be significantly different and the Tukey pairwise comparison identified significant differences between all six of these elements.

Faculty senate leaders agreed most strongly with the Campus Life Collaborations of approving student conduct codes (x̅=4.80), approving student initiatives (x̅=4.75), and collaboration with other governance bodies (x̅=4.71). Presidents agreed most strongly with collaboration with other governance bodies (x̅=4.01), deciding on the campus physical environment (x̅=4.00), and approving student conduct codes (x̅=3.95). Although two of the three were both the most agreed upon activities for collaboration, their agreement levels were significantly lower for presidents.

In the Work Life Collaboration category, faculty senate leaders agreed most strongly with the elements of deciding upon work evaluation processes (x̅=4.88), faculty workload (x̅=4.81), and deciding upon fringe benefits (x̅=4.51). College president agreed most strongly with deciding upon faculty workload (x̅=4.00), work evaluation (x̅=3.95), and physical campus resources (x̅=3.78). Again, there was some similarity between what faculty senate leaders and presidents perceived to be areas of collaboration, yet the presidents agreed at a significantly lower level than the faculty senate leaders.

Discussion and Conclusions

For college presidents, the faculty senate has become the de facto academic senate; that is, the contemporary faculty senate is becoming increasingly pigeon-holed within the framework of what happens in the classroom, and presidents seem to have full, strong agreement on this role. They did not, however, see the breadth of responsibilities that senate presidents reported. The problem or friction that arises from this is that faculty senates do not have a clear idea of what they should be doing, and as a result, believe that they should be doing everything. And, without a clearly defined notion of what shared governance should include with faculty, the likelihood of an effective environment for collaboration becomes less likely to exist.

The onus for defining effective collaboration does not sit exclusively with faculty senate leaders, as college president’s share in the responsibility and actually must lead in the proclamation of what a collaborative environment might look like or what might be expected. From an administrative perspective this is a complex and difficult consideration. There is a distinct difference between sharing authority and giving it away, and by inviting collaboration, leaders invite dissension and opposition.

The idea of conflict in decision-making is welcome in democracy, as such give and take and transparent debate increases the likelihood of accountability to the citizenry. Although populist decision-making can have serious repercussions, as what is popular in the short-term might actually be destructive in the long-term. A critical distinction for the academy, however, is the determination as to the extent that the institution is a democracy as compared to a public service (acknowledging the role differentiation for private institutions). As a public enterprise, the goals of the institution become critical guidelines, and the sharing of authority and responsibility for decision-making may or may not be truly central to the ideology of what must be accomplished by the institution.

Democratic practice in public agencies are conceptually a strong and positive management practice, but as court cases have found (see Connick v. Meyers, Miles, 1997; also see Cloud, 2018), supervised employees are not promised a role in decision-making and have a limited ability to criticize their employers.

The question of employer criticism, in the current discussion, the faculty member’s right to criticize the employing institution is often claimed to be appropriated under the conceptions of free speech protections and academic freedom and tenure, although such arguments lack legal standing and are frequently couched with the language and guidance recommended by professional bodies such as the American Association of University Professors. Herein lies the primary challenge for college presidents, as they must navigate the expectation of participation by both constituents (faculty, staff, and students) and supervising governing boards. Success for college presidents will ultimately be in their ability to negotiate and create expectations from their perspective on what role various governing groups should hold and what powers they can utilize.

As shown in these limited findings, faculty perspectives on shared governance indicate their perception that they should have a say in how the entire institution is governed. Such thinking, while idealized, lacks the important, critical element of accountability for many faculty senates, and is made more difficult, often, by the speed of decision-making. When faculty governing bodies cannot feel the consequences of their actions and the timeliness of their actions on a personal and professional level, their sense of decision-making will be limited.

Ultimately, the modern university, replete with complex, diffused goals, must navigate the tradition of shared governance and align it with the reality of contemporary decision-making. This means that faculty as well as administrators must engage in open dialogue about expectations and outcomes, and each part must ultimately be held accountable to them and each other.

References

Armstrong, W. P. (1999). Trends and issues of a community college faculty senate: The Jefferson State case study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL.

Birnbaum, R. (1989). How colleges work the cybernetics of academic organization and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Birnbaum, R. (2004). The end of shared governance: Looking ahead and looking back. In W. Tierney and V. Lechuga (eds.), Restructuring Shared Governance in Higher Education, New Directions for Higher Education No. 127 (pp. 5-22). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cloud, R. C. (2018, April). Governance in community colleges: Legal and policy issues. Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Council for the Study of Community Colleges, Fort Worth, TX.

Gilmour, J. E. (1991). Participative governance bodies in higher education: Report of a national study. In R. Birnbaum (ed.), Faculty in governance: The role of senate and joint decision making. New Directions for Higher Education, No. 75 (pp. 27-40). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Johnston, S. W. (2003). Faculty governance and effective academic administrative leadership. In S. L. Hoppe and B. W. Speck (eds.), Identifying and Preparing Academic Leaders, New Directions for Higher Education, No. 124 (pp. 57-63). New York, NY: Wiley.

Miles, A. S. (1997). College law (2nd. Ed). Tuscaloosa, AL: Sevgo.

Miller, M. T. (1999). Conceptualizing faculty involvement in governance. In M. T. Miller (ed.), Responsive Academic decision making, involving faculty in higher education governance (pp. 3-28). Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

Miller, M. T. (2003). Improving faculty governance. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

Miller, M. T., & Nadler, D. P. (2019, in press). Student and faculty senate agenda alignment: A test of comprehensive shared governance. Journal of Higher Education Management, 34(1).

Miller, M. T., Williams, C., & Garavalia, B. (2003). Path analysis and power rating of communication channels in a faculty senate setting. In M. T. Miller and J. Caplow (eds.), Policy and university faculty governance (pp. 59-74). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Rose, K. (2012). Organizational citizenship behaviors in higher education: The relationship between behaviors and performance outcomes for individuals and institutions. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR.

Rosser, V. J. (2003). Historical overview of faculty governance in higher education. In M. T. Miller and J. Caplow (eds.), Policy and university faculty governance (pp. 3-18). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Schoorman, D. (2018). The erosion of faculty governance. In J. DeVitis and P. A. Sasso (eds.), Colleges at the crossroads, taking sides on contested issues (pp. 237-251). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Sibley, W. A. (1998). University management 2010. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

Waugh, W. L. (2003). Issues in university governance: More “professional” and less academic. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 585, 84-96.

Table 1. Identification of Survey Respondents

Table 2. Areas of perceived collaboration between College Presidents and Faculty Senate Leaders