Women and the University Presidency: Increasing Equity in Leadership

Tania Carlson Reis

Gannon University

Marilyn L. Grady

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Dr. Tania Carlson Reis, Gannon University, reis001@gannon.edu

Abstract

Women remain underrepresented in university presidential positions (American Council on Education, 2017). In this narrative study, eight women presidents of Carnegie Classified public doctoral granting universities were interviewed to understand how they navigated a route to the position. Findings indicate that perceptions of gender, and opportunities for professional development, complicated the presidential path for women. Also, building leadership capacity was noted as important to sustaining and increasing women leaders in higher education.

In 2017, the American Council on Education (ACE) published their 8th report in the American College President series. First published in 1986, ACE has collected data on the descriptive characteristics of presidents leading U.S. colleges and universities for more than 30 years. According to ACE, in 1986, the profile of the typical U.S. college president was a white male older than 50 years of age with an earned doctorate, and tenure of six years in the position (American Council on Education, 1986). According to ACE’s 2017 report, the typical college president is a white male, older than age 60, with a doctorate, and tenure of seven years in the position. Thus, after three decades of data collection, the typical U.S. college president grew slightly older and stayed one year longer; but, the pictorial profile remained unchanged.

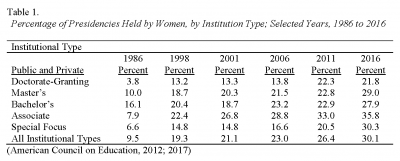

In regard to gender, the ACE report (1986; 2012; 2017) shows a challenging history for women university presidents. In 1986, women represented 9.5% of all university and college presidents. That number grew to 21.1% by 2001, and 30.1% by 2016. Although encouraging, the slow increase of women presidents is less equal for women leading doctoral granting institutions. These institutions reported less than 14% of women leading in the presidential position for the years 1998 through 2006. Also, the increase of women presidents at the doctoral level reported in 2011 decreased when reported in 2016. Thus, in reference to institutional size, the majority of women university presidents continue to lead at master’s, bachelor’s and two-year or special focus institutions (American Council on Education, 2017).

The limited number of women leading doctoral granting institutions does not reflect institutional enrollment. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2017), female students comprise 56% of all students enrolled in post-secondary education. Since 2009, women have earned the majority of doctoral degrees, and in 2016 earned 52.1% of all doctoral degrees awarded (Okahan & Zhou, 2017). Thus, gender and leadership in higher education has not kept pace with gender and enrollment. The slow rise in the number of women presidents signals a need to investigate ways women navigate the position. The ACE data provides a compelling platform, and a need to examine the narratives that form the numbers.

A review of the literature reflects that historically, women have been underrepresented in leadership positions in both corporate and educational arenas. The cause of this has been attributed to gender barriers, discrimination, and late entrance into the workforce and academia (Eagly & Carli, 2007c; Glazer-Raymo, 2008; Kark & Eagly, 2010; Rhode & Kellerman, 2007). According to Glazer-Raymo (2008), the series of laws enacted in the early 1970’s targeted at equal rights opened doors to women, and allowed colleges and universities to balance gender enrollment. This shift in legislation provided access for women but did not result in a supportive hiring framework.

Eagly and Carly (2007a,c) described the evolving structure of the workplace. The traditional glass ceiling, which allowed women to see the corporate top without being able to access it, has been replaced by a complex maze filled with barriers and redirections (Carli & Eagly, 2016; Eagly & Carli, 2007a,c; Kark & Eagly, 2010). Women, moving into leadership positions, must negotiate both tangent issues, such as maternity leave and childcare, and perceptional issues affected by gender as it relates to leadership authority.

Several studies investigated Role Congruity Theory (Bosak, Sczesny & Eagly, 2012; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly & Maladinic, 2011; Eagly & Wood, 2013) and its relationship to women in leadership. Role Congruity Theory states that individuals are expected to behave in accordance with stereotypical expectations. In regard to gender and leadership, men are expected to exhibit strong agency whereas women are expected to show sensitivity and care. The complication of this thinking compounds when women must lead through decisive and direct action. When a woman moves outside the norms of expected behavior, she is often perceived as inauthentic or too male. This leads to criticism of the woman leader that centers on her behavior within the boundaries of gender stereotype.

In higher education, where men hold long tenures in leadership positions, follower perceptions of women leaders create an added barrier. This does not mean that leadership effectiveness is measured by gender, but rather, the complexities of gender, as related to leadership, make moving into leadership positions within a patriarchal culture challenging for women. Navigating these barriers successfully is a daily process for women university presidents; and, it offers a rich narrative of how women leaders negotiate leadership success.

Methodology

This study used a narrative qualitative methodology to collect the leadership stories of eight women university presidents leading public doctoral granting institutions. Research was completed with IRB approval. The purpose of the study was to identify and describe how women presidents who lead public doctoral research universities attain leadership. The study was guided by two research questions.

- How do women university presidents navigate barriers to leadership?

- How do women university presidents create leadership success?

A search of the Carnegie Classification of Institutes of Higher Education using the Classification Descriptor: R1 Doctoral Universities: Highest Research Activity and R1 Doctoral Universities Higher Research Activity yielded 222 institutions of higher education. These institutions represent the top research universities in the United States, both private and public, as defined within the Carnegie framework. According to the American Council on Education (2017) report, women are most likely to lead public institutions. Also, as flagship institutions, public research universities represent a similar funding and governance structure as opposed to private institutions.

To maintain a bounded sample (Creswell, 2013), the results were filtered to reflect only public universities. This resulted in 157 institutions. A manual search of each university was completed via the internet to determine the gender of the university’s president, and resulted in 24 potential participants. Of those potential participants, eight agreed to be interviewed for this study.

It is important to note characteristics of the sample. The number of women presidents in the Carnegie Classification categories Doctoral Universities: R1 Highest Research Activity and R1 Higher Research Activity are very low. Only 15% of public universities in this category had a woman president in 2017. As part of the data collection for this study, a Google newsfeed was initiated to alert the researchers of any changes in university leadership at the institutions being tracked. In twelve months of data collection, this resulted in 175 news alerts related to the 24 women presidents. The alerts were coded into three subject categories: contract renewal, performance review, and campus problems related to leadership. Although this data was used to triangulate the findings, it also provided evidence of the pressures associated with university leadership, and how those pressures put a minority group in a fragile position. The low number of women presidents leading research institutions shows the need to understand their experiences.

Data were collected during a one-hour in person semi-structured interview at the participant’s institution. The researchers traveled to each university to meet the participant in her office, and collected field notes related to the interview surroundings. The interviews were audio recorded and hand coded for themes that reflected the research questions. Narrative coding (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) was applied to identify actions, events and story lines within the leadership experiences of the participants. Two cycle coding methodology (Miles, Huberman & Saldaña 2014; Saldaña, 2013), guided by the research questions, organized the narrative patterns into categories and emerging themes.

Findings

The narratives of the women presidents, each told through a personal lens, resulted in a rich description of the leadership experience. Three themes emerged from the study: Gender, Professional Development, and Building Leadership Capacity. These themes identified critical areas in which the participants faced a barrier or implemented a skill to move their leadership forward. Data from the narratives tell the story behind the national statistics, and offer a compelling description of how women experience the rise to university leadership.

Gender

Gender expectation was the most common barrier experienced by the participants. Women experience a greater bias in leadership positions in both business and higher education (Bornstein, 2008; Eagly & Carli, 2007a; Madden, 2011). All of the presidents interviewed voiced comments congruent with stereotypical expectations of gender and leadership. Women are expected to exhibit female-oriented traits of warmth and care. Men are expected to behave agentic and strong (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Koenig et al., 2011; Sczesny, Nater, & Eagly, 2019 ). When women behave outside these believed stereotypes and cross the boundaries of expectation, they are criticized.

One participant said, “I think that women have a certain presumption to overcome.” Another president said, “You never really hear the words powerful or distinguished being used when people talk about woman. It’s usually in a more derogatory way of describing strength.” A third participant said, “I’m having trouble with the [foundation] here because they think they’re an independent body and they don’t want me telling them what to do. And I often think if I were a man in this position telling them, would they be different?” A fourth participant summarized her experience as a woman president:

You’re always having to prove yourself. Always, in this. Because you’re different in the position. Most of these positions are held by men. Most of them are very traditional. And so you’re always having to prove yourself. And so, that’s just a fact of life.

For the participants in this study, the challenges of gender were linked to follower perceptions. Each woman president voiced confidence in her leadership role but remained aware of her minority status. Gender made a challenging position more fragile. As one president described:

Because now you’re at the top of the heap, and you’re probably in a position where there’s a lot of people who are either suspicious or envious or whatever. And sexism will, and continues to rear its ugly head. You’re always going to be dealing with people who don’t think you can do the job. Usually they’re men. You’ve got to be stubborn and persevere through many things that I don’t think my male counterparts have to face in any regular way.

Gender perceptions resonated as a reminder for each participant as she imitated her leadership style. One example was the process of leading with teams. Each woman president spoke consistently of creating and relying on teams in regard to leadership and decision making. One president had a team of people she indicated were instrumental to her leadership.

To me, it’s always been about team building. Who are you willing to surround yourself with, and are you willing to find people who are smarter than you to do the jobs that are critical to making the university operate?

A second participant described her “kitchen cabinet” as the people she valued within her leadership team. She said, “They’re my brain trust. You know, they’re the people that I talk over everything with. I seek their input on virtually everything.”

A third participant equated team leadership to sustainable leadership.

When you think about succession management, it’s not just are there other people here who could take over? You’ve got to think, what if I’m not here tomorrow? And I think people who don’t do that put their institution at high risk. That’s not just a female thing, that’s men and women.

She then added, “But I think women, because they tend to lead in a more consensus style, are more likely to build that sustainable system.”

Being a university president requires the ability to be decisive. The challenge for these women was finding a way to exhibit individual leadership within a team approach. Creating a shared vision is a tenet of successful leadership (Kouzes & Posner, 2012). Yet, for women, team leadership may be perceived as less effective. As one participant said, “those who believe presidents are supposed to be in charge with an iron fist might look at me and say ‘I don’t know that she’s in charge of anything.”

Women leaders tend to behave more communal and male leaders more agentic (Eagly & Carli, 2007; Eagly et al., 2003; Eagly & Wood, 2013; Sczesny et al., 2019). Although each president led from a point of shared decision making, she also made an effort to keep her public behavior congruent with that of an agentic leader. The balance of being a direct leader within the context of gender, was something the participants in this study understood.

One participant described the challenge of making a high risk decision and owning that risk as part of the leadership process. She described being a leader as “willing to make decisions that others would not” but also as “a balance between listening and acting.” She continued by describing a time that she needed to make a decision related to student safety.

I called together the most trusted people on campus to give me advice on what we should be doing with external communications, with our internal communications and to support our students. I really didn’t know either way whether I was making the right choice.

She ended her narrative of the experience by saying, “that was a difficult moment for me.” Even with team input, she knew the focus of the decision would be on her. She said, “at the end of the day, it was my decision.”

For these women, being the source of a decision had pragmatic implications. Followers expect leaders to make decisions when decisions need to be made. Using group input and a team approach exemplifies good leadership practice (Zaccaro, Rittman, & Marks, 2001). However, for women, a decision made with group input risks being perceived as weak leadership. The communal approach of women leaders is well-received by followers but direct leadership is better understood (Carli, 2015; Eagly, 2013). Thus, gender complicates the leadership paradigm.

The women in this study were aware of the stereotypical boundaries of their leadership. Each woman consciously led through a team approach but communicated as a single leader. The challenge of being a woman, and needing to exhibit a strong leadership personae was compounded by follower perception.

As one participant summarized:

There are expectations of the role. You are expected to be, I don’t know, motherly. You know, people expect you to behave in certain ways, and if you behave in role inconsistent ways, they’re often upset with you.

Professional development

The career pathway to becoming a university president requires the accrual of academic and leadership experience. Building faculty teaching experience, a portfolio of research, and multiple leadership positions into a career plan takes dedication and time. This is likely the reason that the average age of a college or university president is 62 years (American Council on Education, 2017). For the participants in this study, the need to accumulate relevant experience was both deliberate and challenging as women.

One participant described her professional training as “I didn’t really look for administrative positions but I kind of accreted them and they were never paid. They were kind of in addition to everything else I was doing.” To gain administrative experience, this president took on multiple unpaid positions during her career span. Engaging in leadership, even without compensation, honed her talents and increased her visibility.

I was a training director for [university research center], which was also, you know, an unpaid position. No course relief or anything. I just sort of went ahead and did it on top of everything else. And I found out I was really good at doing this, and still keeping up my research and doing all my teaching. One of the associate deans said to me at one point ‘you know, in the dean’s office, we know if we want something done right, we go to [you]. That’s the reputation I got; and, it was a great reputation to have.

When asked why she continued to opt-in to non-paid positions, the president answered, “Because I thought that I could make a difference.” Her volunteer efforts were not part of a plan to someday lead a research university; but, the efforts capitalized over time to build her career.

More or less fortuitously, I got a pretty good background in money and budgeting. Nobody told me I needed to do that, but I did. I mean, that is an absolute box you must check off if you’re going to go on. Didn’t set out to say to myself, you’ve really got to learn all this stuff to be an administrator. But, I did learn it, and that proved to be really helpful.

Another participant described the necessity of administrative experience. She said, “I’ve said to people, if you’re interested in this route, you have to start early enough. I mean, you’re not going to go from being a faculty member to provost in one step.” However, she acknowledged the challenges women face in gaining professional experiences.

I mean, there’s a lot of culture that goes into who, who gets started. I mean at some level, you do have to be good at what you do. But some of it is, you know, where’s your first stepping stone? And was it an opportunity that was, or is, provided for women with the same regularity as men? I would say not.

She described the internal fortitude women must possess in pursuing career advancement. Being a minority member means “the men aren’t going to pick you. They’re not going to see you as a leader.” However, “if they don’t see you as a leader,” she said, “do you use yourself as a leader?”

According to Bornstein (2008), women with presidential aspirations must take responsibility for their own portfolio. Women need the experience. Yet, they must seek out these experiences in whatever way they can find them. This often includes unpaid or under-recognized positions. For women, it is important to act as leader even when leadership is not formally assigned. On the surface, acting as a leader without the acknowledgment of the position seems unfair. However, for women, skill building was a self-directed process.

As one president described:

I think that’s more characteristic of women. Men have bigger egos probably than women. Most of the time or many times. But they get very oriented toward the title of the position. I’m not.

When asked to give advice to women working towards high level university leadership, one participant responded:

Take on opportunities to lead, whether it’s chairing a committee, a taskforce, a fellowship – any of those kinds of opportunities to get close to leadership, and take some risks, and get out of your comfort zone. And each of those experiences is like adding a tool to your knapsack.

In summary, the participants in this study engaged in leadership opportunities for the purpose of leadership development without the guarantee of a formal job. Leadership was not an assigned promotion on the proverbial ladder. It was a holistic choice that required risk and confidence that any opportunity to lead, even a volunteer, unpaid opportunity, would capitalize overtime, and end in a recognized leadership position.

Building leadership capacity

Each participant described the path to the presidency as an indirect route. Being a university president was not part of a plan, or a single aspiration, but rather the end result of a long career of administrative movement. Each woman attributed career momentum to a person or persons that encouraged her to seek administrative opportunities. Conversely, each participant denied having a single leadership mentor. Instead, each woman experienced a series of interactions with different individuals who offered support or encouragement at critical career points. The narratives of the women presidents contained references to mentors, from graduate school faculty to committee chairs to higher administrative officers. Mentorship was not formal or direct. Instead, mentorship happened in informal moments or conversations. Interestingly, the majority of the mentors described by participants were male.

One president described the person who encouraged her to embrace a new position outside of faculty teaching, “you know, it makes a big difference having somebody say to you that you can do this.” Another participant described her experience saying “the Dean wanted me to do it, my colleagues encouraged me to do it and I was persuaded that I could do some good if I did it.” A third participant said,

I had a guy, a mentor along the way that used to tell me, he says, ‘if you ever get the opportunity, be a Dean.’ He said that is the best position in the university because if you’re doing a good job, the Provost will leave you alone, and you get your own domain.

On his advice, she applied for a position, and became a Dean. She laughed as she recalled the story. “So, now, I get asked to speak to the Deans. And they tell me that I am the only person they’d met that that said it was such a great job!” She points to that experience as pivotal not only in building her career title, but also her love for leadership.

I loved it! I loved it! It’s about problem solving. I mean, I had a math department that was very difficult. I sat with them so much and got to know them so well, one of the faculty members said to me one time, “would you just leave us alone for a while?’ I said, ‘I’ve grown very fond of you!’

For the women in this study, the move to administration was not a linear path. It was the accrual of experiences that leveraged overtime. These experiences were often connected through personal interactions or recommendations, and each woman used the experience to create new opportunities. In short, there were no gifts or favors given to these women. Rather, there were suggestions made by higher level administrators to “apply to be a department chairperson” or “Have you thought about the provost position?” These women exhibited good leadership qualities, and in turn, were often encouraged to pursue higher opportunities.

The women presidents in this study also acknowledged creating both formal and informal leadership programs for female students and faculty. One president described the changing pipeline.

I see a huge pipeline coming right behind me. I love that. I absolutely do. I absolutely know it. It’s like the pyramids. We’re standing on each other’s shoulders. There’s no doubt about that. The senior administration behind me is now, half of them are women.

All of them are going to have opportunities to go other places.

It was evident in the interviews that all the participants supported developing leadership in others, and creating sustainable leadership for their campus. In regard to women’s leadership, the participants were in favor of women’s leadership programs for students and faculty but reported greater satisfaction from informal connections and conversations with aspiring women leaders. As one president said, “Over time, I’ve just become more and more skeptical of these single gender [leadership] programs.”

It was the informal connections that seemed the most impactful. As one president described her position,

I said when I was interviewed, if I send a message that women should aspire to the highest positions of leadership, that’s a fabulous message. I mean not every woman will be a university president, nor should they, nor should they want to be. But I’ve had a number of both students, graduate students and faculty say it suddenly changed their perspective on administration and the role of women. I had some graduate students see me in a restaurant, and they had tears in their eyes. It meant so much to them to have a woman leader.

In regard to inspiring other women to pursue a university presidential position, one participant said,

They should certainly explore it, think about it. It’s not going to appeal to everybody. And believe me, there are plenty [of] fabulous women on the faculty, and they are so good at that. They certainly shouldn’t go into administration just because we had a woman president, so [you] should do that [too]. It’s more a matter of having that be an avenue that they can explore, think about, is this something you’re interested in or not? There are some women on the faculty, I wouldn’t want them in administration because they are fabulous at what they do. They are so good as teachers and scholars, and so inspirational to the women graduate students. Why have them leave that?

For these women, supporting women’s leadership at any level was as important as building the next generation of women university presidents. The participants in this study reported the university presidency as a long-term end goal that did not follow a straight or guaranteed path.

Said one president,

I don’t know very many women that plan this kind a thing, and if they do, they’re crazy. So you know, you do make certain decisions during your career that ultimately can lead in this direction; and if it works out, it’s often times serendipitous that it does.

The participants described their jobs as university presidents as “a 24/7 job” or “I get recognized everywhere. I can’t get my teeth cleaned without someone saying ‘I have a kid at [your university].” One president described her university as a “small city.” Another participant described being a university president as a “lifestyle choice.” In short, as one participant said, being a university president of a public research university is “pretty much an unrealistic expectation.” The time consuming nature of the job may affect the number of people who want to pursue the position.

I think there’s going to be a challenge nationally of finding people who want to do this work. Particularly with the explosion of endowed chairs and professorships. Where [faculty] have, you know, economic freedom, not just intellectual freedom. So it becomes a little bit more of a struggle to recruit deans and department chairs and those kinds of things. I think it’s going to be a struggle.

Good leaders foster competence and confidence in those they lead (Kouzes & Posner, 2012). In the case of the women presidents interviewed, each president could name more than one individual who had supported her in developing her leadership skills. The fact that the majority of these mentors were male, supports a broader conversation about the power of male mentors (Raggins & Cotton, 1992:1999; Searby & Tripses, 2006).

Each woman president acknowledged her desire to support emerging women leaders. Although none of the participants identified a formal process to do that, each participant described meeting with women in small groups, or one-to-one for informal conversations. The participants also acknowledged their larger societal impact by simply being in the position. As one president summarized:

You know your legacy as the first woman president of a land grant university. But, if what [I’ve] done is convey the message that this is a job, and I’d like to think I’m doing it well enough that nobody’s going to say ‘well, it wasn’t bad for a woman.’ I want them to say actually, she was a very good president, and the whole thing about a woman, just doesn’t even have to come up again. Because it turns out a woman was a successful president. Not just okay, but successful.

Conclusion

Leading a public research university requires significant skills. For women, the challenge of leadership is complicated by gender bias and perceptions. The minority status of women in the position necessitates an added layer of awareness. In this study, gender informed both the leadership style and actions of the university president.

For these women presidents, the double bind (Eagly & Carli, 2007b) was a reality that informed every leadership decision. Women tend to lead with a team oriented focus where men are more autocratic. There is no evidence that men make better decisions than women but decisions made by men carry a greater degree of believability (Bornstein, 2008; Eagly, 2013; Eagly & Carli, 2007a,b). Men are given points for strong delivery or direct action. Women are criticized for the same behavior. Consensus building through team leadership is an effective leadership style; but, team leadership exercised by a woman can be perceived as an indecisive leader (Eagly, 2005; Eagly & Carli, 2007a,b,c; Eagly & Chin, 2010). In the end, a woman leader’s effective style may be mitigated by gender perception.

A university president is required to have specific skills and experience. For women, building leadership credentials may require taking unpaid or volunteer positions. The support of individuals who open leadership opportunities and offer encouragement to engage in new responsibilities, can help women climb the leadership ladder. In the end, leadership credentials build both legitimacy and social capital (Bornstein, 2008). Although challenging, the “can do” attitude required of women gives an added benefit to those women who reach a leadership position.

The average university president is over age 60 (American Council on Education, 2017). There is a need to develop new leaders, and women are well poised to move into the position. Fifty-seven percent of faculty and senior staff in higher education are women (American Council on Education, 2012). Although formal leadership programs are helpful, informal support can be beneficial (Eagly, 2013; Authors, 2016). Women presidents have traveled a complex path to the position. With so few women leaders, each path to the presidency is highly individualized. Sharing stories with younger women aspiring to leadership is an important contribution by women university presidents.

Leadership for women is complicated. Perceptions of leadership, and how leaders are expected to behave, are informed by gender. The majority male presence in the university presidency, means that women are advancing to a position with a historical male context. Gender does not define skilled leadership; but, leadership is understood differently through follower interpretation. Women university presidents understand this phenomenon. Knowing how leadership works for women does not make university leadership easier. Instead, knowing how and when gender matters allows women to lead effectively and authentically. Higher education is slow to change. It is up to women to build a new and authentic paradigm.

References

American Council on Education. (1986). American College President Study. Washington, DC: ACE.

American Council on Education. (2012). American College President Study. Washington, DC: ACE.

American Council on Education. (2017). American College President Study. Washington, DC: ACE.

Bornstein, R. (2008). Women and the college presidency. In J. Glazer-Raymo (Ed.) Unfinished agendas: New and continuing gender challenges in higher education (pp. 162-184). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bosak, J., Sczesny, S., & Eagly, A.H. (2012). The impact of social roles on trait judgments: A critical reexamination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(4).

Carli, L. (2015) Women and leadership. In A. M. Broadbridge & S. L. Fielden (Eds.) Handbook of gendered careers in management: Getting in, getting on, getting out. (pp. 290 – 304). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Carli, L.L. & Eagly, A.H. (2016). Women face a labyrinth: An examination of metaphors for women leaders. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 31(8), 514-527.

Clandinin, D. J. & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Eagly, A. H. (2005). Achieving relational authenticity in leadership: Does gender matter? The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 459-474.

Eagly, A. H. (2013). Women as leaders: Paths through the labyrinth. In M.C. Bligh & R.E. Riggio (Eds.). Exploring distance in leaders-follower relationships: When near is far and far is near (pp. 191-214). New York, NY: Routledge.

Eagly, A.H. & Carli, L.L. (2007). Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harvard Business Review. 9, 63-71.

Eagly, A.H., & Carli, L.L. (2007). Overcoming resistance to women leaders: The importance of leadership style. In B. Kellerman & D.L. Rhode (Eds.). Women and Leadership (pp. 127-148). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Eagly, A.H. & Chin, J.L. (2010). Diversity and leadership in a changing world. American Psychologist, 69(3), 216-224.

Eagly A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573-598.

Eagly, A.H. & Mladinic, A. (1994). Are people prejudiced against women? Some answers from research on attitudes, gender stereotypes, and judgments of competence. European Review of Social Psychology, 5(1), 1-35.

Glazer-Raymo, J. (2008). The Feminist Agenda. In J. Glazer-Raymo (Ed.). Unfinished agendas: New and continuing gender challenges in higher education (pp. 1-34). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kark, R. & Eagly, A.H. (2010). Gender and leadership: Negotiating the labyrinth. In J. C. Chrisler & D.R. McCreary (Eds.). Handbook of gender research in psychology (pp. 443 – 468). Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media.

Kouzes, J. M. & Posner, B. Z. (2012). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations. (5th ed.) San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Madden, M. (2011). Gender stereotypes of leaders: Do they influence leadership in higher education? Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, 9, 55-88.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Okahana, H., & Zhou, E. (2017). Graduate enrollment and degrees: 2006 to 2016. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Ragins, B. R. & Cotton, J. L. (1993). Gender and willingness to mentor in organizations. Journal of Management, 19(1), 97-111.

Ragins, B. R. & Cotton, J. L. (1999). Mentor functions and outcomes: A comparison of men and women in formal and informal mentoring relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 529-550.

Rhode, D. L. & Kellerman, B. (2007). Women and Leadership. In B. Kellerman & D.L. Rhode (Eds.), Women and Leadership (pp. 1-62). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Searby, L. & Tripses, J. (2006). Breaking perceptions of “old boys’ networks:” Women leaders learning to make the most of mentoring relationships. Journal of Women in Educational Leadership, 4(3), 29-46.

Sczesny, S., Nater, C., & Eagly, A.H. (2019). Agency and communion: Their implications for gender stereotypes and gender identities. In A. E. Abele and B. Wojciszke (eds), Agency and communion in social psychology (pp. 103 – 116). New York, NY: Routledge.

United States Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Enrollment in elementary, secondary, and degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level and control of institution, enrollment level, and attendance status and sex of student: Selected years fall 1990 through fall 2026. (Table 105.20). Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_105.20.asp?current=yes

Table 1. Percentage of Presidencies Held by Women, by Institution Type; Selected Years, 1986 to 2016