The Next Generation of Community College Presidents: Results of a National Study on Who They Are, How They Prepare, and How They Lead

Matthew A. Cooney

Governors State University

Kenneth W. Borland

Bowling Green State University

Correspondence related to this article should be addressed to Dr. Matthew A. Cooney, Interdisciplinary Leadership Doctoral Program, Governors State University, mcooney@govst.edu

Abstract

Community college scholars and professional organizations are preparing for the expected turnover of the current generation of community college presidents and the present study examines potential community college presidents who may fill this leadership void. The researchers present information on senior, community college administrators who indicated they are interested in pursuing the community college presidency (N=436) as part of a national study including how the potential community college presidents utilize transformational leadership and if their utilization of transformational leadership differs based upon their current position and highest degree earned. The researchers conclude with recommendations on next steps to move the potential community college presidents from interested in the position to holding the position.

There are multiple changes occurring in community colleges including offering of baccalaureate degrees, calls for free tuition, and increased emphasis on outcomes (Cohen, Brawer, & Kisker, 2014); however, the biggest challenge is that these changes may occur under new leadership due to the impending retirements of community college presidents. Shults (2001) termed the community college presidents’ retirements as a “Leadership Crisis” as he reported that 45% of all community college presidents planned to retire within six years and community college presidents who entered the position did not feel prepared for the position. Additional scholars and professional organizations expanded on the leadership crisis as planned retirements of community college presidents within 10 years ranged from 84% in 2007 (Weismann & Vaughn, 2007) to 75% in 2013. (American Association of Community Colleges [AACC], 2013a)

Given the impending retirements, it is essential to prepare the next generation of community college presidents. There are multiple ways that one can prepare to become a community college president including learning through previous positions (AACC, 2013; Eddy, 2010; Jones & Warnick, 2012) and attainment of a doctoral degree (Hammons & Miller, 2006; Jones & Warnick, 2012; McNair, 2015). Not only is it important to know how community college presidents prepare for the position; but also if this preparation involves utilization of transformational leadership.. The AACC recommended that community college leaders focus on transformational leadership skills by noting the need to “develop your personal toolkit for transformational leadership skills that allow you to galvanize employees to support the mission, vision, and goals of the institution” (2013b, p. 6).

This national, descriptive, correlational study identified potential community college presidents based upon their interest in the position as part of a larger study examining transformational leadership in community college executive administrators such as senior academic affairs officer (SSAO), senior student affairs officers (SSAO), senior academic and student affairs officers (SASAO), and senior finance and administrative officers (SFAO). In this article, we focus on results that suggest how potential community college presidents presently use transformational leadership and if their utilization of transformational leadership differs based upon current position and highest degree earned which are two essential preparation practices for future community college leaders.

The expanse of community colleges’ service, expanding functions, and their need for transformational leadership, all in an unfolding “crisis” of president retirement accompanied by successors’ sensed under preparation leaves community college stakeholders questioning. Therefore, we address three important questions about potential community college presidents.

- Who are the interested potential community college presidents?

- How are they preparing for the presidency?

- How are they presently leading, in regard to transformational leadership?

Literature Review

Scholars and professional organizations placed increased importance on the study of community college presidents including their preparation and career pathway partially because of the expected turnover in the position (Eddy, 2010; Jones & Warnick, 2012; McNair, 2015; Weisman & Vaughn, 2007). The change in leadership in the community college presidency is connected to the young age of community colleges (Fulton-Calkins & Milling, 2005; Hassan, Dellow & Jackson, 2010; Shults, 2001). The first community college was established in 1901 and community colleges did not grow in large numbers until the 1960s and 1970s (Thelin, 2004). Current community college presidents who began their career during the boom of community colleges are now ready for retirement (Boggs, 2003; Fulton-Calkins & Milling, 2005; Hassan et al., 2010). Shults (2001) detailed the turnovers leave “an enormous gap in the collective memory and the leadership of community colleges (p.2)

Community college organizations including the Achieving the Dream Foundation, the AACC, the American Association of Community College Trustees, the Aspen Institute, the League for Innovation in the Community College, and Student Success Initiatives at the University of Texas, Austin are committed to preparing the next generation of community college presidents in order “to leverage the strengths and resources of each organization to address this significant transition in leadership in ways that align recruiting, selection and development practices with the goal of increasing student success” (AACCT, 2012, para. 3).

The retirements of community college presidents can offer opportunities for growth and development of the institution (The Aspen Institute and the Achieving the Dream Foundation, 2013; Eddy, 2010; Eddy, Sydow, Alfred, & Garza- Mitchell, 2015; McNair, 2015); however, many current administrators are not interested in the position (Guthrie, 2001; Waggoner, 2016). Community college presidents described the position as emotionally charged and undesirable because of the certainty of crisis (Maslin-Ostrowski & Floyd, 2012); constant scrutiny by campus and community members (Floyd & Maslin-Ostrowski, 2013); and risky because of the numerous situations outside community college presidents’ control (Jones & Johnson, 2014). This negative portrayal of the position might be a deterrent for individuals in senior administration positions at community colleges who could be preparing themselves for the position. This present study will present information on those who, despite the negative portrayal of the position, are still interested in perusing the community college presidency.

Preparation for a Community College Presidency

In order to prepare future community college presidents, one must understand how previous community college presidents prepared for the position. They have often described the importance of previous positions in preparing to lead the institution (Eddy, 2008; Jones & Warnick, 2012; McNair, 2015; Nevarez & Wood, 2010; Romano, Townsend, & Mamisieishvilli, 2009). The most common career path to the community college presidency is through academic affairs (e.g., American Council on Education, 2012; Amey & VanDerLinden, 2002; Amey, VanDerLinden, & Brown, 2002; Bailey & Kubala, 2001; Birnbaum & Umbach, 2001; Eddy, 2010); however, the pathway into the presidency is diversifying as senior student affairs officers (SSAO) and senior finance and administration officers (SFAO) are entering the presidency (Sandoval, 2011; Welch, 2002; Kiley, 2011).

Community College presidents detailed the importance of the doctoral degree for obtaining an interview for a community college presidency and reported the degree was a prerequisite for the position (Jones & Warnick, 2012; McNair, 2015). Eighty-five percent of community college presidents hold a doctoral degree (ACE, 2012) and many community college presidents obtain a doctoral degree in community college leadership

Theoretical Framework

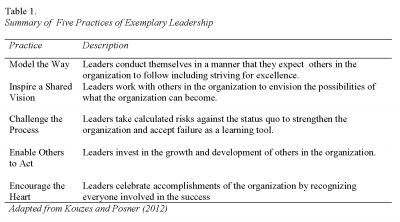

Northouse (2016) defined transformational leadership as “a process whereby a person engages with others and creates a connection that raises the level of motivation and morality in both the leader and the follower” (p. 171). Kouzes and Posner (2012) developed one of the most famous models of transformational leadership—The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership which include (1) model the way, (2) inspire a shared vision, (3) challenge the process, (4) enable others to act, and (5) encourage the heart. Key concepts from each practice are highlighted in Table 1.

The Five Practices posited by Kouzes and Posner (2012) have been researched extensively in higher education, often through the same assessment tool used in this study: The Leadership Practices Inventory-SELF (Kouzes & Posner, 2013). Scholars have examined the five practices in the context of community colleges (Broome, 2003; Butler, 2009; Dikeman, 2007; Grafton, 2009; Holt, 2003), student affairs (Jones, 2009; Oliver, 2001; Rozeboom, 2008; Smith 2013), and senior higher education leaders (Dikeman, 2007; Maitra, 2007; Relken, 2014; Stephenson, 2002; Stout-Stewart, 2005).

Research Questions

As part of the authors’ national study addressing the demographics and use of transformational leadership practices among potential community college presidents, the researchers collected data in the summer of 2016 using a quantitative, cross-sectional design (Citation removed to protect blind review). The present study, in addition to presenting demographic data on potential community college presidents, has two research questions:

- Do aspiring community college presidents’ mean scores on the LPI-SELF differ based upon current position?

- Do aspiring community college presidents’ mean scores on the LPI-SELF differ based upon highest degree earned?

Sample

The researchers surveyed SAAOs, SSAOs, SASAOs, and SFAOs currently employed at 2-year associate’s degree-granting institutions listed in the 2016 Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education in the United States. These institutions (N=924) offer the associate’s degree as the highest degree conferred or bachelors’ degrees conferred by the institution account for less than 10% of total degrees (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, n.d.).

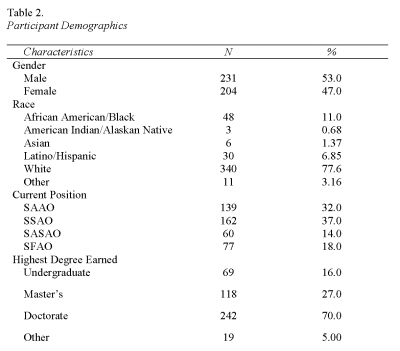

Contact information for the participants was gathered through the Higher Education Directory. If the contact information was unavailable, the researchers contacted the institution directly. If no information was provided, the positions were omitted from the sample. The SAAO, SSAO, SASAO, and SFAO were identified based on the job position titles indicated in previous studies that corresponded to one of the four positions. Higher education institutions have a wide variety of organization structures; thus, not all institutions in the sample have each position. Researchers distributed 2,711 surveys to senior community college administrators and received 656 useable responses. In this study we examine only senior administrators who indicated they were interested in a community college presidency, thus the final sample was 436 aspiring community college presidents. Table 2 lists demographic data on the participants.

Instruments and Variables

Because scholars and professional organizations have asserted the importance of transformational leadership among community college leaders (AACC, 2005, 2013; Cohen et al., 2014; Eddy, 2010), the researchers used the Leadership Practice Inventory-SELF (Kouzes & Posner, 2013). This survey measures self-perceived use of five transformational leadership practices: model the way, inspire a shared vision, challenge the process, enable others to act, and encourage the heart. The LPI-SELF contains 30 statements, and respondents report how often they engage in a particular behavior using a 10-point, Likert scale (1 = almost never; 2 = rarely; 3 = seldom; 4 = once in a while; 5 = occasionally; 6 = sometimes; 7 = fairly often; 8 = usually; 9 = very frequently; and 10 = almost always). Six statements correspond with each of the five practices of exemplary leadership, and each practice represents its own scale. A higher score on the LPI-SELF indicates the leader more frequently uses the corresponding transformational leadership practice. Internal reliability for each scale ranges from .814 to .900, and Posner (2015) indicated the LPI had “excellent face validity” (p. 11) because of its roots in qualitative research on personal best leadership scenarios. Additionally, participants were provided a demographic survey regarding their personal and professional background. These instruments were combined using Qualtrics software.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, not all SAAOs, SSAOs, SASAOS, and SFAOs were included because no complete list of community college administrators holding these positions exists. Even using multiple methods for locating such senior administrators, some could not be included in the study. Additionally, the content and scope of the professional portfolios of SAAOs, SSAOs, and SASAOs may differ greatly depending on the specific institution. Thus, differences that may affect use of transformational leadership may exist within groups representing each position.

Results

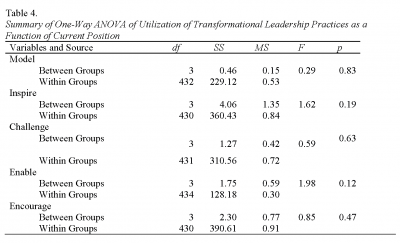

The researchers used one-way ANOVA tests to answer research questions one and two. The independent variable for research question one was the participant’s current position (SAAO, SSAO, SASAO, SFAO) and was highest degree earned for question two. The highest degree earned was grouped into four categories: undergraduate (associate’s or bachelor’s degree), master’s, PhD/EdD, and other. The dependent variable was the participant’s mean score on each of the five scales of the LPI-SELF. Five one-way ANOVA tests were conducted for each question. The one-way ANOVA test was appropriate for these research questions because the researchers were examining differences in mean scores for a single dependent variable between multiple independent variables (Mertler & Vannata, 2013).

Question 1

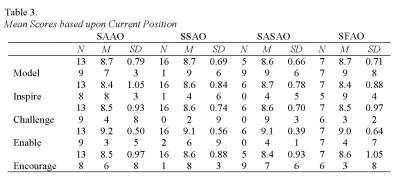

The first research question examined if potential community college presidents mean scores on the LPI-SELF differed as a function of current position. The mean scores of potential community college presidents are located in Table 3 and a summary of the one-way ANOVA is located in Table 4. Potential community college presidents’ mean scores on the LPI-SELF did not statistically significantly differ as a function of current position for model the way, F(3, 432)=.029, p= 0.83; inspire a shared vision, F(3, 430)=.1.62, p=0.19; challenge the process, F(3,431)=0.59, p=0.63); enable others to act, F(3,434)=1.98, p=0.12; and encourage the heart F(3,430)=0.85, p=.47).

Question 2

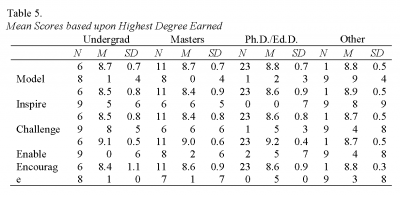

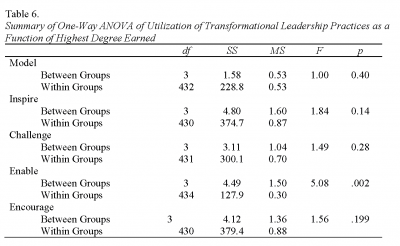

The second research question examined if potential community college presidents’ mean scores on the LPI-SELF differed as a function of highest degree earned. We conducted five one-way ANOVA tests to determine whether aspiring community college presidents differed in self-reported utilization of transformational leadership practices as a function of highest degree earned. The degree categories included undergraduate degrees (associate’s and bachelors degrees), master’s degrees (including M.B.A), doctoral degrees (Ph.D. and Ed.D) and other (J.D and multiple terminal degrees). The mean scores are located in Table 5 and the full results of the ANOVA are located in Table 6.

Potential community college presidents’ mean scores on the LPI-SELF did not statistically significantly differ as a function of highest degree earned for model the way, F(3, 432)=1.00, p= 0.40; inspire a shared vision, F(3, 430)=1.84, p=0.14; challenge the process, F(3,431)=1.49, p=0.28); and encourage the heart F(3,430)=1.56, p=.199). Potential community college presidents mean scores on the LPI-SELF did statistically significantly differ as a function of highest degree earned for the transformational leadership practice of enable others to act, F(3, 434)=5.08, p=.002. A Tukey post-hoc test was conducted and potential community college presidents who hold a doctorate degree (M=9.25, SD=0.47) as highest degree earned reported statistically significantly higher (p=.001) mean scores on the transformational leadership practice of enable others to act than potential community college presidents who hold a masters degree as highest degree earned (M=9.02, SD=0.66).

Discussion

Scholars of community colleges and community college professional organizations have emphasized the need to succeed the many retiring community college presidents with persons who are prepared, and who understand and utilize transformational leadership. To describe the potential successors, we asked three questions. Who are the interested potential community college presidents? How are they preparing for the presidency? How are they presently leading, in regard to transformational leadership?

From within 924 community colleges, 656 of 2,711 surveyed senior community college administrators (SAAO, SSAO, SASAO, SFAO) submitted useable responses to related questions. Within those 656 responses, 436 persons indicated they were interested in a community college presidency. Literally hundreds of current community college administrators are interested in perusing a community college presidency.

While assuming they are presently gaining applicable/transferable experience in their current leadership roles, we observe that a high percentage of these potential community college presidents have earned doctoral degrees. Also, as desired by leading voices for community college success (community college organizations, current and former community college presidents, and scholars), the potential community college presidents already engage in a high degree of transformational leadership. This appears to be differently accomplished within particular leadership roles, scopes of responsibility, and across the five transformational functions based upon position. However, this finding suggests, if not indicates, the potential community college presidents are making progress toward the desired community college president practice of transformational leadership.

Implications for Practice

Potential community college presidents who participated in leadership development programs reported statistically significantly high mean scores on the LPI-SELF for all five scales. The research design did not allow for cause and effect; however, the correlation supports other research that detailed benefits for participation in these community college leadership development programs sponsored by national organizations. Therefore, with a large number and percent of interested, academically qualified, professionally developed, and Transformational Leadership experienced (and possibly oriented) community college presidential successors, what are implications for further response to the perceived crisis?

We put forward a suggestion that the field expand the presidential developmental role of community college organizations and the presidential successor developmental role of sitting community college presidents. Specifically, move from a broad sense of presidential development to one focused on championing these interested, rather well equipped, and leading individuals into presidencies.

There needs to be a means for sitting and retired presidents to discover and nurture their potential successors’, these developing leaders’ interest in the community college presidency. Begin by replacing the fear of competition, stigma of arrogance, and other undesirable concerns many associate with a person’s upward career aspiration. Replace it with a greater concern for the future of community colleges, and with a call for safely identifying, directly honoring, and purposefully shaping leaders’ presidential ambitions.

Championing these interested and leading individuals into presidencies can then be conducted by secure, transparent leaders of community college organizations as well as sitting and retired college presidents. Set Transformational Leadership as the central desired outcome of this intrusive instruction and mentoring of potential presidents. With education of various types, but most certainly on-the job opportunities, community college organizations and experienced presidents need to give interested leaders modeling followed by a potential president’s own real life experiences that require and shape the potential presidents’ utilization of more aspects of transformational leadership.

This needs to be done within a potential president’s own division and, even more important for potential presidents, across all divisions: Give them responsibility that encompasses the big picture, keys to success, and experiences that test their transformational leadership of the entire institution. Why? Potential community college presidents in this study serve as SAAO, SSAO, SASAO, and SFAO and they did not indicate statistically significantly differences in utilization of transformational leadership according to the mean score on the LPI-SELF. Though their utilization of transformational leadership may not differ, the context in which they utilize these transformational practices will vary according to job responsibilities and roles. As potential presidents, they need (and will enjoy) opportunities that allow them to utilize their transformational leadership in different contexts. For example, the SFAO should exercise opportunities to utilize transformational leadership in a student affairs or academic affairs context, or across the entire institution.

Championing potential presidents must also include presidential encouragement; experienced president putting their transformational leadership successes and names before others within their own institutions, in the field, and before search firms. Regarding searches, championing also requires guiding the potential president into and through the “mystery” of presidential search strategies and navigating the search process. It requires the community college organization and sitting presidents to take pride in seeing one of their own leaders emerging into a presidency.

Future Research

The researchers utilized one-way ANOVAs to explore differences in self-reported utilization of transformational leadership practices as a function of current position and highest degree earned. The magnitude of these experiences can be further studied by conducting statistical analysis that include multiple variables in the same equation.

Similarly, a quantitative approach provides statistical data on potential community college presidents; however, further qualitative research on potential community college presidents can illuminate how potential community college presidents utilize transformational leadership practices and navigate a path to the presidency. A cross-case analysis between potential community college presidents who successfully navigated a transition to the presidency and those who did not obtain the position can provide valuable information on the professional preparation of the next generation of community college presidents.

Finally, continued analysis on the demographics of potential community college presidents can assist in diversifying the pipeline to the presidency. As community colleges serve more than 50% of racially underrepresented college students in higher education, it is troubling that racial diversity is not well represented in the current study.

Conclusion

From the national study, we found an encouraging description of a large number of potential community college presidents. While further research will enhance what we know about potential community college presidents, we have offered a sound description of who they are, how they have prepared for the presidency, and how they have led with transformational leadership. The number of potential community college presidents that are already in community college leadership positions is high. Many of them have terminal degrees and have engaged presidential development programs. They are using transformational leadership. These findings should encourage America’s community college sector in this perceived unfolding period of crisis, one rooted in transforming community college functions and high occurrences of presidential retirements. Nevertheless, we encourage community college organizations and experienced presidents to take additional steps to address the crisis with championing this large number of potential presidents.

References

American Association of Community Colleges. (2013a). Competencies for community college leaders (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Association of Community Colleges. (2013b). Data points: Pending C.E.O. retirements. Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

American Association of Community Colleges. (2013b). Data points: Pending C.E.O. retirements. Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

Association of Community College Trustees. (2012). Community college associations join forces to prepare future CEOs. Washington, DC: Association of Community College Trustees.

American Council on Education. (2012). The American college president 2012. Washington, DC: Author.

American Council on Education. (2013). On the pathway to the presidency: Characteristics of higher education senior leadership. Washington, DC: Author.

Amey, M. J., & VanDerLinden, K. E. (2002). Career paths for community college leaders (Research Brief Leadership Series No. 2). Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

Amey, M. J., VanDerLinden, K. E., & Brown, D. (2002). Perspectives on community college leadership: Twenty years in the making. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 26, 573-589.

Aspen Institute & Achieving the Dream Foundation. (2013). Crisis and opportunity: Aligning community college presidents with student success. Retrieved from Aspen Institute web site: https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/crisis-opportunity-aligning-community-college-presidency-student-success/

Bailey, T. K., & Kubala, G. M. (2001). A new perspective on community college presidents: Results of a national study. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 25, 793-804.

Birnbaum, R., & Umbach, P. D. (2001). Scholar, steward, spanner, stranger: The four career paths of college presidents. Review of Higher Education, 24, 203-217.

Boggs, G. (2003). Leadership context for the twenty-first century. In W. E. Piland & D. B. Wolf (Eds.), Help wanted: Preparing community college leaders in a new century [Special issue]. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2003(123), 15–25).

Broome, P. H. (2003). The relationship between perceptions of presidential leadership practices and organizational effectiveness in southern community colleges (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3116144)

Butler, S. L. (2009). Ethical perspectives and leadership practices in the two-year colleges of South Carolina (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3369246)

Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. (n.d). About Carnegie classification. Retrieved from http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu/

Cohen, A. M., Brawer, F. B., & Kisker, C. B. (2014). The American community college (6th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Dikeman, R. (2007). Leadership practices and leadership ethics of North Carolina community college presidents (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3280917)

Eddy, P. L. (2010). Community college leadership: A multidimensional model for leading change. Herndon, VA: Stylus.

Eddy, P. L., Sydow, D. L., Alfred, R. L., & Garza-Mitchell, R. L. (2015). Developing tomorrow’s leaders: Context, challenges, and capabilities: The futures series on community colleges [Kindle edition]. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com

Floyd, D. L., & Maslin-Ostrowski, P. (2013). Leaving a community college presidency: The inevitable career transition. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 37, 242-247.

Fulton-Calkins, P., & Milling, C. (2005). Community college leadership: An art to be practiced: 2010 and beyond. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 29, 233-250.

Guthrie, J. (2001). Been there; done that: Life after the presidency. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 25, 243-250.

Grafton, K. S. (2009). Presidential transformational leadership practices: Analysis of self-perceptions and observers at community colleges in Oklahoma (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3357441)

Hammons, J. O., & Miller, M. T. (2006). Presidential perceptions about graduate-preparation programs for community colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 30, 373-381.

Hassan, A. M., Dellow, D. A., & Jackson, J. (2010). The AACC leadership competencies: Parallel views from the top. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34, 180-198.

Holt, D. J. (2003). Administrator behavioral leadership practices: A comparative assessment of administrators and observers at selected community colleges in Texas (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3088147)

Jones, S. D. (2009). A study of the relationship between leadership practices and organizational effectiveness in student affairs (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3384700)

Jones, S. J., & Johnson, B. (2014). Are community college presidencies wise career moves? Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 38, 300-310.

Jones, S. J., & Warnick, E. M. (2012). Attaining the first community college presidency: A case study of new presidents in Texas. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 36, 229-232.

Kiley, K. (2012, July 31). Meet the new boss. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://insidehighered.com

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2012). The leadership challenge (5th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2013). Leadership practices inventory: Self report. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Maitra, A. (2007). An analysis of leadership styles and practices of university women in administrative vice presidencies (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Ohiolink Dissertations and Theses database.

Maslin-Ostrowski, P., & Floyd, D. L. (2012). When the time comes for the community college president to step aside: Daunting realities of leading. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 36(4), 291-300.

McNair, D. E. (2015). Deliberate disequilibrium: Preparing for a community college presidency. Community College Review, 43(1), 72-88.

Mertler, C. A., & Vannatta, R. A. (2013). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical application and interpretation (4th ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak.

Nevarez, C., & Wood, J. L. (2010). Community college leadership and administration: Theory, practice, and change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Northouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Oliver, S. W. (2001). The leadership practices of chief student affairs officers in Texas: A comparative analysis (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3011772)

Posner, B. Z. (2015). Bringing the rigor of research to the art of leadership: Research behind the five practices of exemplary leadership. Retrieved from http://www.leadershipchallenge.com/UserFiles/Bringing%20the%20Rigor%20of%20Research%20to%20the%20Art%20of%20Leadership.pdf

Relken, N. A. (2014). Examining emotional intelligence and perceived leadership practices among college enrollment services administrators: A descriptive study (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3624336)

Romano, R. M., Townsend, B., & Mamiseishvili, K. (2009). Leaders in the making: Profile and perceptions of students in community college doctoral programs. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 33, 309-320.

Rozeboom, D. J. (2008). Self-report and direct observer’s perceived leadership practices of chief student affairs officers in selected institutions of higher education in the United States (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3333760)

Sandoval, G. R. (2011). Exploring the path from student services professional to community college president (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). San Diego State University, San Diego, CA.

Shults, C. (2001). The critical impact of impending retirements on community college leadership (Research Brief Leadership Series, No. 1). Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

Smith, M. A. (2013). Senior-level student affairs’ administrators’ self-reported leadership practices, behaviors, and strategies (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3564020)

Stephenson, S. (2002). Promoting teamwork: Leadership, attitudes, and other characteristics of a community college chief financial officer (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertation and Theses database. (3055346)

Stout-Stewart, S. (2005). Female community-college presidents: Effective leadership patterns and behaviors. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 29, 303–316.

Thelin, J. (2004). A history of American higher education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Waggoner, R. (2016). Pipelines to leadership: Aspirations of executive-level community college leaders to ascend to the presidency (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 10109833)

Weisman, I. M., & Vaughn, G. B. (2007). The community college presidency 2006 (Report No. AACC-RB-07-1). Washington, DC: American Association of Community Colleges.

Welch, M. C. (2002). Leadership frames of female presidents of American research universities (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database. (UMI No. 305554000)