The Effectiveness and Priorities of the American College President: Perceptions from the Faculty Lounge

G. David Gearhart

Daniel P. Nadler

Michael T. Miller

University of Arkansas

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Michael Miller, Higher Education Program, University of Arkansas, mtmille@uark.edu

Abstract

The American college presidency has become increasingly complex, particularly due to the wide variety of demands placed on the position. Indeed, the effectiveness of a president is often seen through the lens of different constituents. Historically, the faculty have played a key role in determining the success of a president, and the current study sought to identify the perceptions of faculty members regarding the effectiveness of presidents. Additionally, the study sought to compare faculty perception of desired versus actual effectiveness of presidential responsibilities.

During the past 50 years, the American college presidency has evolved at a rate never before seen in the history of higher education. The role must now be responsive to multiple constituencies at every hour of the day and every day of the week. The explosive engagement of technology in all aspects of higher education has fueled this change, and one result is the diversification of those holding the presidential position. This trend has grown during past decades, as the skills required to manage colleges and universities has evolved from largely curriculum and faculty oversight to highly complex financial dealings, fundraising, image and brand management, along with a long list of other challenges (American Council on Education, 2019).

Those holding presidential positions today come from a broad range of backgrounds. There has been an increase in presidents coming from fundraising and political backgrounds, coming from the private sector and big business, state and federal public agencies, and even individuals coming from student affairs and enrollment management (Braswell, 2006; Martin, 2018). The cumulative effect of the changing role of the presidency as well as those holding the role has been a growing, gradual removal from the faculty who provide the instruction on these college campuses (Selingo, 2017).

The earliest higher education institutions in North America were administered by a faculty member who took on additional responsibilities, such as fundraising and student discipline (Miller, 1993). The primary responsibility of these individuals, though, was that of providing instruction. As institutions grew to be more complex, the instructional role diminished and the professional presidency emerged. There have been residual active debates about whether or not the individual holding the presidential role should have experience as a faculty member, although there has been little consensus about the impact of such experience.

One outcome of the changing professional presidency is the declining support and trust that faculty members have in these leaders (Waugh, 2003). Some will be quick to argue that in any large, complex, financial institution, there should be a distinct differentiation of roles and responsibilities, and those senior executives who hold leadership positions do not necessarily behave differently or more effectively if they have had teaching and research experiences. Faculty members, however, often counter such arguments, indicating that they believe such experience in the classroom and laboratory are critical to how an institution is managed.

The purpose for conducting the current study was to explore how faculty members perceive the role of the presidency and the training and experiences that best serve as a preparation for serving in the role. These findings are important not just to presidents currently serving in their roles, but to governing boards looking to find leaders for their campuses as well as associations and agencies that provide training and transitional help for new college presidents.

Background of the Study

College Presidents. Due to the nature of the presidential role, the individual holding the position has the primary responsibility and authority over an institution. Typically reporting to a governing board or a systems-level administrator, the role of the president has the obligation to assure the completion of work and obligations for all academic and business related matters (Smith, 2006). This role has grown in scope and complexity, and today encompasses all facets of a complex organization that in most ways resembles a private business rather than a non-profit, often state government sponsored, entity. Responsibilities for fiscal management, including investments, real estate holdings, benefit negotiations, information technology security protocol all dominant the current presidential agenda, often segmenting the ability of presidents to respond to curricular conversations or program quality management (Morris, 2017). The role now dictates delegation of massive responsibility, requiring the position to provide oversight, vision, direction, and strategic leadership; specific content knowledge is required, yet time constraints and complexity require a very different approach to institutional management (Tolliver & Murry, 2017).

Much has been written on the evolution of the modern college presidency, tracing the roots of the position from faculty assignments and term appointments to the current trend of career administrators who hold no other position than senior institutional leadership roles. This suggests, and perhaps means, that presidents today have little understanding of the academic responsibility of their institutions and the elements of student development that have historically been the foundation of the academy.

College presidents are currently being recruited and hired from a wider variety of roles than ever before in history (Selingo, 2017). Coming from careers in the private sector, public service, politics, and even the military, the roster of college presidents is more diverse today than at any other time in history. This diversity of experiences does not necessarily mean that an individual is more or less qualified for the role, but rather, that they may approach the responsibilities of the position with different priorities and different strategies for accomplishing their perspectives on what the institution should be undertaking. Historically, a president rising from an academic career would presumably have a better understanding and prioritization of student and faculty needs, and possibly, less business-savvy. Conversely, a president coming from the private sector might be more well prepared to develop a strong financial future for an institution. Neither scenario is necessarily a zero-sum proposition, however, as presidents have the luxury of staffs and constituents who are prepared and often willing to share their thoughts and ideas about how institutions should run and what they should be trying to accomplish (Fry, Taylor, Watson, Gavillet, & Somers, 2019).

The range of constituents informing presidents of perspectives on institutional performance is reflective of the diversity of measures that might be applied to indicate whether or not a president is effective in the role. Some presidents assume their positions with specific agendas to repair problems or build programs or platforms, and other presidents might be hired into the role for other reasons, including political appeasement. The extent that a president is accepted into the role, however, can provide the morale and within-institution support for the president’s agenda. And, regardless of the complexity of the agenda, there are critical elements in which an institution must succeed, including the delivery and offering of coursework. The result is that faculty, whether happy or discourage by the president’s method of appointment, must demonstrate some form of commitment to the president’s efforts.

College Faculty. As with all of higher education, the faculty member has changed dramatically in higher education during the past 50 years. Increasingly diverse and from diverse graduate experiences, these individuals are more stratified than ever before, making use of modified faculty titles that did not exist 10 or 20 years ago. Increasingly there are Professors of Practice, Clinical faculty, research faculty, contingent faculty, and traditional assistant, associate, and full professors. Faculty are paid on different scales, expected to conduct different activities, and are measured and evaluated on different criteria. And although collective bargaining arrangements have attempted to keep pace with what is being asked of faculty members, union membership and protections have declined for faculty. The cumulative result is that institutions can and do control faculty in ways that did not exist in the past, and that the collective ability of faculty to challenge institutions with power has declined dramatically.

Data support the trend that the number of full-time, tenured faculty members has decreased throughout higher education (Flaherty, 2018).There are subsequently multiple consequences to the employment of non-tenured faculty members, including, but not limited to, a decreased number of faculty who will find comfort and ease in challenging administrative decision-making. A residual consequence, then, is that formalized faculty governance bodies struggle with defining their power to challenge administration and represent the faculty as a singular body. As faculty responsibilities shift and are segmented, these bodies become less able to voice a singular perspective on what they need to accomplish their work on campus (Rhoades, 1998). Different types of faculty appointments have different types of expectations of their work environment.

As faculty perspectives on the academy subsequently shift, it becomes increasingly difficult to align their work and needs with presidential backgrounds. Although the majority of all college presidents still arrive in their positions with some academic experience, the diversification of the faculty body means that the president is less well equipped to even understand, appreciate, and advocate for the experiences of so many different types of faculty members.

An additional consideration for presidential leadership is the ability to garner support and cooperation in advancing different institutional priorities. Broadly, this means that presidents have to use their formal and informal power and authority to create feelings of consensus and agreement about different priorities, creating buy-in to improve the implementation of the priority or initiative being advanced by the president (Nadler, Miller, Hamza, & Gearhart, 2019). Because this relationship is so important, presidents must find ways to demonstrate their respect of faculty and the work that they do. Alternatively, faculty must increasingly try to understand the complexity of the presidency, and must find credibility, sincerity, and agreement with the president’s efforts. This makes understanding the activities of the president critically important, and ultimately, this understanding will either lead to initiative implementation or not. The informal coupling between the president and faculty is unique to higher education (Birnbaum, 1988), and similarly, a reflection of the complexity of attempting to manage an industry that based on creativity and individuality.

Leading the Contemporary Campus. Higher education is frequently being noted for sitting at a crossroads of evolution, attempting to define its future and how it can and will serve seemingly a growing number of constituents (DeVitis & Sasso, 2018). A major part of this confrontation is public calls for accountability that have been present in the academy for well over five decades, but have only recently become so contentious that these debates help or harm institutions. Additionally, competition from private-sector postsecondary institutions that have the support of the federal government are forcing traditional colleges to explore new and different ways of serving learners. And, in addition to there being more options for students, there are an increasing number of students who are making use of their options, exercising their right to transfer coursework between institutions, building their transcripts based on their personal, academic needs and desires (Jacobs, Miller, Lauren, & Nadler, 2004).

The landscape for college presidents and faculty is also inclusive of increasing state regulations, as legislatures and policy makers use their positions to craft directives that force institutions to be efficient and responsive to state needs. Performance funding efforts that promote timely degree completion or majoring in STEM fields, for example, illustrate how state oversight bodies are attempting to direct the efforts of the academy (Fincher, 2015).

Yet another domain that is challenging higher education as never before are the calls for stronger commitments to social justice, recognizing historical, systemic discrimination that is sometimes centuries old, yet being called for reform today. These building names, statues, scholarships, and endowed professorships are being re-examined from a current lens that recognizes disparities in a new way (Anderson, 2020). This requires presidential leadership to be focused and collaborative in redesigning many of the systems that have evolved into their current structure. This also means that many constituents are vocally calling on campus for reform, and the extent and ability of this reform is largely predicated on the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the president.

The litany of challenges facing many organizations in society similarly face higher education, further challenging institutional leadership. Technology uses, security, and costs, growing fringe benefit costs, including funding health care and retirement programs, aging physical facility maintenance, funding source stability, etc. are all issues that college leaders must address in new and creative ways (DeVitis & Sasso, 2018). The current state of the academy dictates a new type of campus leader, and the most challenge and difficult issues these leaders face are rarely academic.

Research Methods

As an exploratory study, a research-team developed survey instrument was used to collect data. Survey items were identified from the literature base reflecting roles, challenges, opportunities, and expectations of the college presidency. The survey was constructed in the spring of 2020 and pilot tested in the summer of 2020. The survey was distributed in the early fall of 2020 to a national sample of 300. The sample was taken from full-time faculty teaching at Association for Public Land-Grant University (APLU) institutions. Using the APLU listing, individual institutions were first selected, and then once an institution was identified, the leader of a faculty senate or similar position was identified, with that individual then receiving the survey instrument.

Those receiving the instrument were asked to rate on a 1-to-5 Likert-type scale to what extent they perceived the identified issue as a desired priority for college presidents, and then to what extent it was an actual priority for college presidents. The intent was to identify the expectation of the contemporary president and to what extent that expectation was being fulfilled. Three follow up survey distributions were used over a 15-day period of time.

Findings

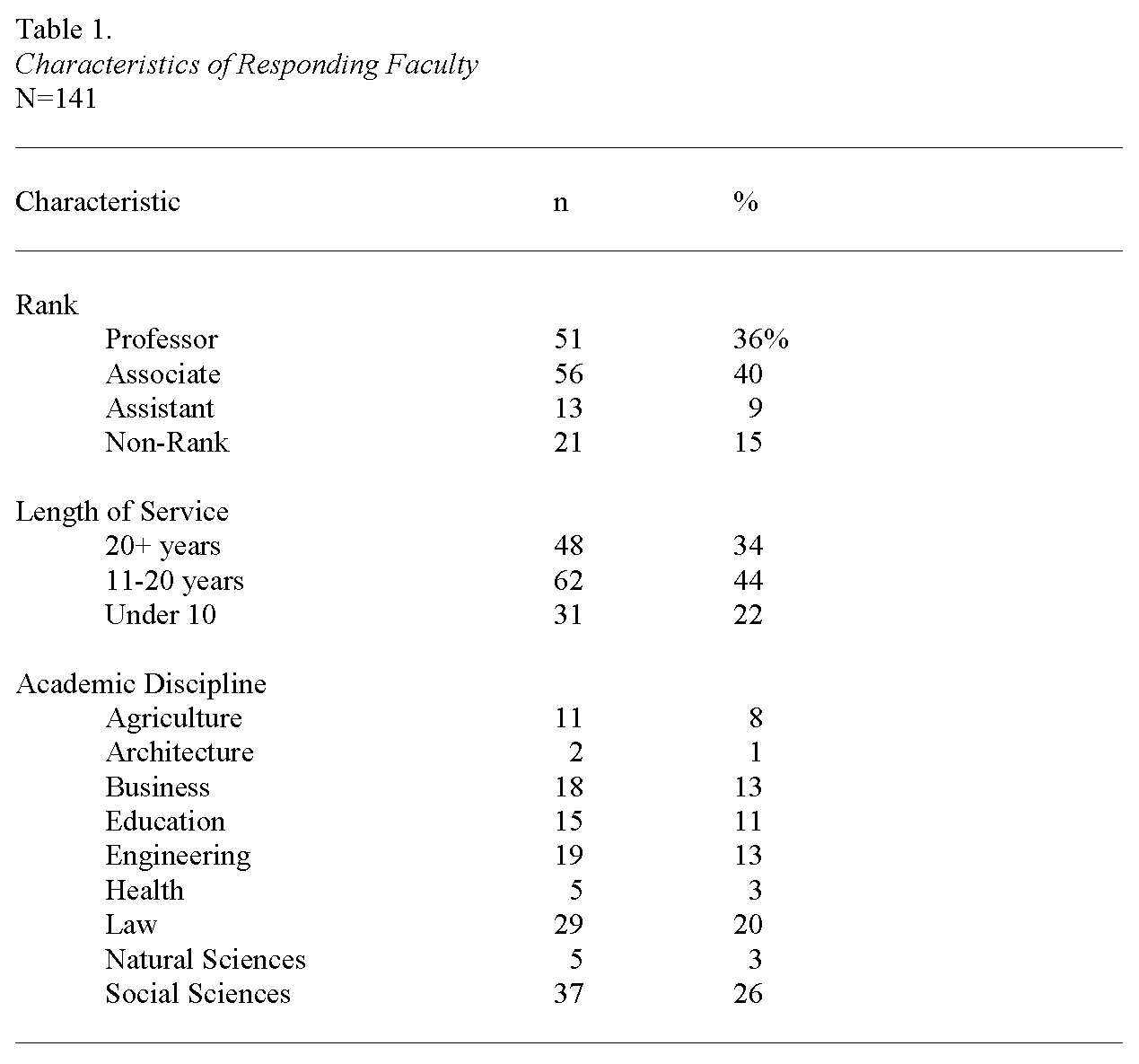

Following the third administration of the survey instrument, a total of 141 usable, complete surveys had been returned for use in data analysis (47% response rate). Of the respondents, over a third (n=51; 36%) held the rank of Professor and over three-fourths (n=110; 78%) had worked at their current institution for more than 10 years. These responding faculty leaders were represented the most from the disciplines of the Social Sciences (n=37; 26%), Law (n=29; 20%), Engineering (n=19; 13%) and Business (n=18; 13%; see Table 1).

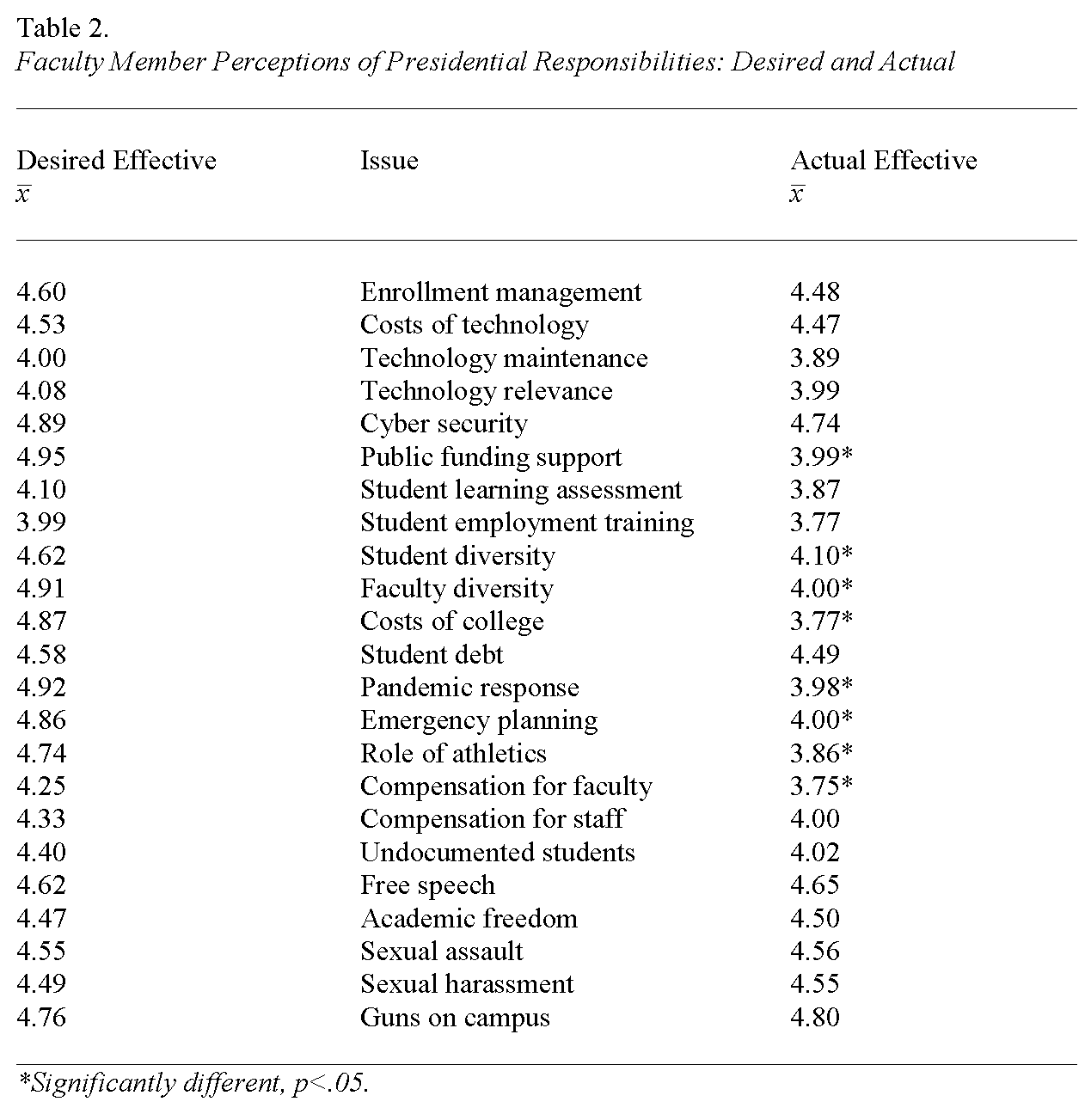

Responding faculty were first asked to identify their agreement with a set of identified issues that they desired their presidents to be effective at addressing. The scale used in this section of the survey included a 1-to-5 Likert-type scale with 1=Strongly Disagree that the issue was a desired priority for presidential effectiveness progressing to 5=Strongly Agree that the issue was a desired priority for presidential effectiveness. The most strongly agreed upon issues were public funding support (x̅=4.95), pandemic responses (x̅=4.92), faculty diversity (x̅=4.91), cyber- security (x̅=4.89), and the costs of college for students (x̅=4.87; see Table 2). The issues that received the lowest overall levels of agreement were still within the Agree-to-Strongly Agree range (4-5), including compensation for faculty (x̅=4.25), student learning assessment (x̅=4.10), technology maintenance (x̅=4.00), and student employment training (x̅=3.99).

Faculty were then asked to use the same 1-to-5 Likert-type scale to rate their agreement on the actual effectiveness of presidents on these issues. The faculty responded with mean scores indicating that presidents were the most effective at addressing guns on campus (x̅=4.80), cyber-security (x̅=4.74), free speech (x̅=4.65), sexual assault (x̅=4.56), and sexual harassment (x̅=4.55). The areas where faculty respondents perceived the president to be the least actual effective included student learning assessment (x̅=3.87), student employment training (x̅=3.77), managing the costs of college (x̅=3.77), and compensation for faculty (x̅=3.75).

Using a series of two-tailed, paired t-tests, eight significant differences (p<.05) were then identified between the desired effectiveness of presidents and their actual performance. In each case, the actual effectiveness of presidents was significantly lower than the desired effectiveness, and these included significant differences for the following areas: public funding support, student diversity, faculty diversity, costs of college, pandemic response, emergency planning, the role of athletics, and compensation for faculty.

Discussion and Conclusions

The current study provides a good picture of the kinds of issues and complexities facing higher education today. These issues, as identified in the literature and included on the survey, portray an industry at a cross-roads, one that has formerly been a public entity and is increasingly become a privatized industry driven by consumer and ‘customer’ demands. This positioning of higher education as being reliant on tuition dollars means that presidents have to make decisions and perform functions that are more akin to political rather than academic behaviors. This is not to intimate that the role must be focused solely on academic matters, but the societal expectation of the modern college presidency is more about serving as a public face for the organization than of moderating student growth and development.

The literature reviewed here, along with the findings of the study, strongly suggest that the presidential role has moved significantly away from academic maintenance. Further solidifying the understanding that presidents have an important role to play in the academy, findings suggest that faculty do not fully appreciate or understand what this contemporary role is. For many faculty, it might be about getting a raise or being paid more money, and for others, it might be providing the strategic leadership to advance the institution. Faculty expect more public support and cost containment for students, but also disagree that presidents are effective in this regard.

The other perspective on these findings could be that presidents have become so political and involved in the external facing of the institution that they are not capable of spending the dedicated time necessary to manage the internal workings of an institution (particularly research institutions). This realm of concern, that of the president no longer being capable of balancing priorities, could also become an issue as institutions look to fulfill their public role and responsibility. At the heart of public higher education is a role that is expected to be filled by an institution. Institutions, however, seem to follow presidential leadership ambitions and frequently take on responsibilities, duties, and activities that are far removed from the chartering mission of an institution as a public entity. Perhaps reframing the public expectation for higher education could result in a redefinition of presidential expectations. Such a radical movement would, however, require strong state and governing board support as well as a patient public willing to use different criteria for thinking about the role of higher education.

References

American Council on Education. (2019). American college president study 2017: Summary profile. Retrieved online from www.aceacps.org/summary

Anderson, G. (2020, July 6). Campuses reckon with racist past. Insidehighered. Retrieved online from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/07/06/campuses-remove-monuments-and-building-names-legacies-racism

Birnbaum, R. (1988). How colleges work. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Braswell, K. H. (2006). A grounded theory describing the process of executive succession at Middle State University. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR.

DeVitis, J. L., & Sasso, P. A. (Eds.). (2018). Colleges at the crossroads, taking sides on contested issues. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Fincher, S. E. (2015). An exploration of performance-based funding at four year public colleges in the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR.

Flaherty, C. (2018, October 12). A non-tenure track position? Insidehighered. Retrieved online at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/10/12/about-three-quarters-all-faculty-positions-are-tenure-track-according-new-aaup

Fry, J., Taylor, Z. W., Watson, D., Gavillet, R., Somers, P. (2019). Who did they just hire? A content analysis of new college presidents and chancellors. Journal of Research on the College President, 3, 72-88.

Jacobs, B., Miller, M., Lauren, B., & Nadler, D. (Eds.). (2004). The college transfer student in America, the forgotten student. Washington, DC: American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers.

Martin, Q, III. (2018). Chief student affairs officers: Transforming pathways to the presidency. Journal of Research on the College President, 2, 30-39.

Miller, M. T. (1993). Historical perspectives on the development of academic fund raising. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 20(3), 237-242.

Morris, A. (2017). Challenges and opportunities facing the community college president in the 21st century. Journal of Research on the College President, 1, 2-8.

Nadler, D. P., Miller, M. T., Hamza, E. A., & Gearhart, G. D. (2019). Faculty senates and college presidents: Perspectives on collaboration. Journal of Research on the College President, 3, 62-71.

Rhoades, G. (1998). Managed professionals, unionized faculty and restructuring academic labor. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Selingo, J. (2017, April 18) Pathways to the presidency. Deloitte Insights. Retrieved online at www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/college-presidency-higher-education-leadership.html

Smith, R. V. (2006). Where you stand is where you sit: An academic administrators handbook. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press.

Tolliver, D. V., III, & Murry, J. W., Jr. (2017). Management skills for the contemporary college president: A critical review. Journal of Research on the College President, 1, 9-17.

Waugh, W. L. (2003). Issues in university governance: More “professional” and less academic. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 585, 84-96.

Table 1. Characteristics of Responding Faculty

Table 2. Faculty Member Perceptions of Presidential Responsibilities: Desired and Actual