Who Did They Just Hire? A Content Analysis of Announcements of New College Presidents and Chancellors

Jessica J. Fry

Z. W. Taylor

Del Watson

Rebecca Gavillet

Pat Somers

University of Texas at Austin

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Z. W. Taylor, Higher Education Leadership Program, University of Texas at Austin, zt@utexas.edu

Abstract

Historically, women and non-binary conforming individuals have not held executive leadership positions at U.S. institutions of higher education at the same rate as men. And although the presidency or chancellorship may be the single most powerful executive leadership position in U.S. colleges and universities, no research has examined how new presidents or chancellors are announced to the public through official, institutional websites. This study analyzes a three-year dataset (2016–19) of 443 press releases announcing new presidents or chancellors at U.S. institutions, paying close attention to how press releases differ based on gender. Findings reveal that men were more likely to have their families mentioned in the press release (43%) than women (30%), while men were also more likely to be internal candidates, interim candidates, and alumni. Implications for research, practice, and gender equity at the executive level are addressed.

Aside from a system-level chancellor or university system board of regents, the college president is arguably the most powerful executive leader in United States higher education. However, throughout history, the college president has looked the same: a “married, graying white man with a doctoral degree,” and despite an increased emphasis on diversity on college campuses over the past few decades, this profile still dominates (June, 2007, para. 1). In 2016, 70% of all college presidents were men, 58% were over 60 years old, and 83% were white (American Council on Education [ACE], 2019a). While the number of women presidents has increased, progress has been slow and women continue to be underrepresented—particularly at research institutions. In 2017, only 8% of women presidents were at doctoral-granting institutions, compared with 37% at two-year colleges (ACE, 2019b).

Educational researchers have examined the complexities of how minoritized women rise among the ranks and achieve the presidency, including how African American and Latina women view their roles as chief executives (Muñoz, 2009; Ramos, 2008; Waring, 2003), how women presidents adjust their leadership style to navigate traditionally masculine spaces (Brown, 2005; Jablonski, 1996; Stout-Stewart, 2005), and how women have been relegated to dean- and provost-level positions in lieu of appointments to the presidency (Brown, 2005)—also known as hitting “the glass ceiling” (Davis & Maldonado, 2015, p. 1; Longman & Lafreniere, 2011, p. 2). However, and equally as important as qualitative and quantitative investigation into the exclusion of women and non-binary conforming individuals from the presidency, no research has examined the institutional rhetoric surrounding the college president, specifically when the president is first introduced to the public and campus community.

Through a critical feminist lens (Wildman, 2007), this critical discourse analysis (van Dijk, 1993) examines a three-year dataset of press releases announcing new presidents or chancellors at postsecondary institutions in the United States between 2016 and 2019 (n=443). Despite the power held by college and university presidents and chancellors, no research to date has examined how these executive leaders are announced upon hire, especially paying close attention to how these announcements differ by gender of the presidential candidate. Due to the fact that women and non-binary conforming individuals do not hold executive leadership positions at colleges and universities in the U.S. at the same rate as men (ACE, 2019a), it is critical to examine how press releases differ based on gender to expand the current literature and interrogate the institutional rhetoric surrounding gender differences in these powerful, authoritative positions.

Literature Review

Women are more educated, more credentialed, and working more than ever before; however, there has not been a proportional increase in the numbers of women found in top-level leadership positions (American Association of University Women, 2016). A gender disparity remains in executive leadership roles despite the fact that women hold advanced degrees and a prominent place in most professional sectors (e.g., healthcare, business, higher education) (Chisholm-Burns, Spivey, Hagemann, & Josephson, 2017). Many rationales have been advanced to explain the lack of women in leadership. A prevalent one is the false narrative that there is a limited pipeline of qualified women to fill leadership roles because women choose not to pursue leadership positions (Beck, 2003). Another is that the “inherent nature” of women—such as emotionality, resistance to risk taking, and irrational methods of decision making—may prevent them from achieving the skills needed to be effective in positions of authority (Beck 2003, p. 2).

The underrepresentation of women in leadership has been framed as a deficit (American Association of University Women, 2016), and the argument has been made that women choose to hold themselves back from becoming leaders (Beck, 2003). This position has since been empirically rejected (Wheat & Hill, 2016).

Historically, there has been a perception that women lack the leadership qualities to succeed in top-level leadership roles. Extremely qualified women may still bear the burden of needing to prove that they are worthy of a leadership position (Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell, & Ristikari, 2011). However, the literature suggests that there may be incentives for closing the gender gap in leadership, as not only do women leaders perform comparably and sometimes better than their male counterparts, but educational organizations benefit when women are well represented in senior leadership (Lyness & Grotto, 2018). Ultimately, women face two forms of prejudice regarding their leadership—a deficit in the acknowledgement of their leadership skills (Beck, 2003) and a less favorable evaluation of their leadership behavior (Koenig et al., 2011).

The concept of leadership as a primarily masculine endeavor hinders the acceptance of women as leaders, and colors the perception of their leadership behavior. Hill et al. (2016) allege that because most leadership positions have been held by white men, “the concept of leadership has been infused with stereotypically masculine traits: aggression, decisiveness, willingness to engage in conflict, strength, and so on” (p. 5). Women are expected to be caring, relational, gentle, and silent whereas leaders are portrayed as tough, decisive, authoritative, and outspoken (Beck, 2003). Consequently, men fit cultural constructs of leadership better, have better access to leader roles, and face fewer challenges in becoming successful (Koenig et al., 2011). There is “an inconsistency between the predominantly communal qualities (e.g., nice, compassionate) that people associate with women and the predominantly agentic qualities (e.g., assertive, competitive) that they believe are required for success as a leader” (Koenig et al., 2011, p. 617). This cultural construct is a major driver of the gender disparity in leadership.

Disparity in leadership has been even greater for women who belong to other minoritized groups, gender identities, or other social constructs. Intersectionality is the interconnectedness of characteristics such as race and gender, and how they interact to discriminate against and disadvantage a group (Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall, 2013; Hopkins, 2018; Wheat & Hill, 2016). According to Wheat and Hill (2016), “Intersecting identities, social context, and power relationships shape the way that people behave and are perceived as leaders” (p. 4). For women of color, the intersection of race and gender further hinders their ability to advance to top-level leadership positions, thus breaking the glass ceiling. Wheat and Hill (2016) found that “women of color face both gender-and race-normed expectations that give rise to even more complex challenges in achieving top leadership roles and leadership legitimacy” (p. 4). Socially dominant constructs of identity include whiteness, masculinity, and heterosexuality (Hopkins, 2018), while intersectionality has been broadened to include dimensions such as sexuality, religion, class, and age (Oikelome, 2017). This intersectional discrimination—and systematic exclusion from power— may affect women’s ability to achieve leadership positions. Organizational members with dominant identities may be more successful, garner greater resources, and achieve more attention than those with multiple identities outside the dominant (Sanchez-Hucles & Davis, 2010).

Women also face cultural barriers to leadership not typically faced by men. Oikelome (2017) posited that women in academia are continually impacted by socially constructed gender roles, despite the fact that higher education touts itself as an environment that fosters and celebrates diversity. In addition, women continue to bear the burden for the majority of household and family responsibilities despite their increased time and expectations at work (Hannum, Muhly, Shockley-Zalabak, & White, 2014). Despite dramatic changes women contributing to the labor force, much of the responsibility for caring for family—both children and elderly parents—devolves unequally to women (Hannum et al., 2014), with empirical research suggest women often sacrifice educational leadership positions to provide family care (ACE, 2019b). Having children benefits men—they are considered more stable and are rewarded with a “family bonus” of higher level positions and higher compensation—whereas women experience a “family (motherhood) penalty” when they have children, with less rapid advancement and less pay (Greenhaus & Parasuraman, 1999, p. 405).

Men continue to be appointed leadership positions at higher rates than women, despite valiant attempts by many to close the gender gap (ACE, 2019a; Davis & Maldonado, 2015; Longman & Lafreniere, 2011). This is consistent across employment sectors, including higher education where women are severely underrepresented in leadership roles compared to men, despite expanded efforts at diversity in hiring and promotion (ACE, 2019a; American Association of University Women, 2016). Women face many barriers to advancement—including structural barriers, which tend to favor masculine models of leadership and exclude women from opportunities (Hannum et al., 2015). Meanwhile, cultural barriers persist with traditional gender roles featuring women as the caretaker (Oikelome, 2017). This intersection of social constructs—such as race, gender, and sexuality—have a greater impact on a woman’s ability to break through the glass ceiling (Hopkins, 2018). This can be amplified in U.S. higher education, which has succumbed to male leadership for decades (ACE, 2019a). These barriers, paired with the tradition of male leaders, have affected the opportunity for women to gain president or chancellor roles in the academy, simultaneously excluding women from serving as role models for younger women, while also perpetuating inequitable gender pay gaps that have persisted in U.S. higher education for generations (ACE, 2019a; American Association of University Women, 2016).

Conceptual and Analytical Framework

This study analyzes institutional press releases announcing new presidents, chancellors, superintendents, and chief executive officers, and is primarily framed by van Dijk’s (1993) critical discourse analysis through a critical feminist lens (Wildman, 2007).

Longitudinal research demonstrates that women and non-binary individuals have been—and continue to be—underrepresented in executive leadership at institutions of higher education in the United States (ACE, 2019a; American Association of University Women, 2016; Ballenger, 2010; Graham, 1978; June, 2007; Madsen, 2008; Moody, 2018; Tunheim, McLean, & Goldschmidt, 2015). One part of pipeline to the presidency is the institutional discourse around searches and appointments. Therefore, we decided to interrogate the language of institutional press releases announcing new executive leadership appointments to critically explore whether these press releases reveal gender biases meant to subjugate women and non-binary individuals, maintaining extant power structures in academia and beyond. Critical feminist theory criticizes mainstream feminist theory for not going “far enough to counter women’s societal subordination” and such critical theories are required to “push feminist theory to recognize a deeper radicalism” (Wildman, 2007, p. 349). As such, this study analyzes press releases, which are a potential form of oppression and subjugation of women and non-binary individuals in U.S. higher education. By examining a form of communication shared widely with an institution’s community and beyond, a critical feminist lens allowed us to explore gender differences between how new executive leaders are announced, and thus, how extant power structures and relations are maintained.

van Dijk’s (1993) notion of critical discourse analysis (CDA) serves to focus on such power structures and relations, seeking to dissect how these structures and relations are “enacted, legitimated, or otherwise reproduced by text and talk” (p. 249). Moreover, the critical targets of CDA are “the power elites that enact, sustain, legitimate, condone or ignore social inequality and injustice” (p. 252). As U.S. institutions of higher education have legitimized the power structure of executive leadership and subsequently excluded women and non-binary individuals from this power structure and subsequent control, this study’s CDA explores “discourse control as a form of social action control, but also and primarily that it implies the conditions of control over the minds of other people, that is, the management of social representations” (p. 257). As a result, it is critical to examine how executive leadership at U.S. institutions of higher education are portrayed in institutional press releases, as such discourse serves to manage social representations of power structures, including individuals and groups in power.

Conceptualizing an executive leader as a unit of analysis, this study employs CDA to outline how executive leaders are socially represented by their institution, and whether these leaders are represented differently depending on their gender. Understanding how executive leaders are introduced to the community—over which they will wield power—will lead to a richer, more contextualized understanding of how new women and non-binary executive leaders are socially represented compared to those who have traditionally held power: men.

Methods

The following sections describe how we gathered data, analyzed it, and addressed the limitations of the study.

Data Collection

All members of the research team work in higher education institutions as faculty members, researchers, or academic professional staff members and subscribe to popular media outlets common in higher education circles, namely Inside Higher Ed and The Chronicle of Higher Education. These news outlets regularly collect institutional press releases announcing new executive leaders at virtually all institution types across the United States and then send these collections to their subscriber base (Lederman, 2019; Piper, 2019). After an exhaustive review of extant literature and research on executive leadership at U.S. institutions of higher education, we discovered that these press releases had not been analyzed and would serve as opportunity to make a unique contribution to the literature and provide institution-specific contexts as to how new executive leaders are announced. As a result, from late 2015 until early 2019, we archived these press releases, resulting in a corpora of 443 press releases.

However, we understood that two publications—Inside Higher Ed and The Chronicle of Higher Education—may not collect and publicize every U.S. institution’s announcement of a new executive leader. Subsequently, we employed Google’s Advanced Search function and programmed an automatic email alert whenever an .edu web address published an article containing the terms “new president,” “new chancellor,” “new superintendent,” “new CEO,” or “new executive leader.” Although it is difficult to verify that this study contains every press release announcing a new executive leader from 2015 to 2019, this approach to data collection was the most robust one available to us.

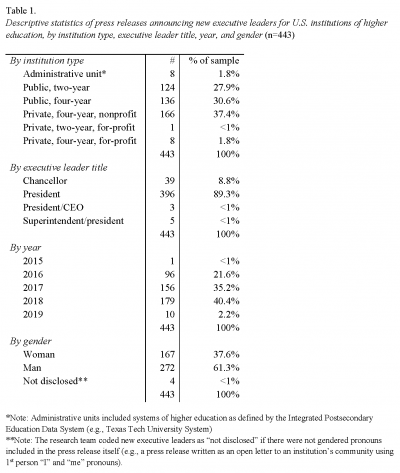

When we located the hyperlink (URL) of each institution’s press release published on the official, institutional .edu website, the following metadata were extracted: name of the institution, title of the executive leader (e.g., president, chancellor, superintendent, CEO), URL of the press release, publication date, title of the press release, body text of the press release, all embedded pictures in the press release, and all embedded videos in the press release. For every press release, we entered the metadata into an online database for ease of collaboration and analysis. Moreover, entering each press release’s metadata allowed us to employ the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019) to integrate institutional variables into the database, including sector of the institution and whether the institution held a religious affiliation. The hyperlink, title of the press release, body text of the press release, all embedded pictures, and all embedded videos were uploaded into a text file and uploaded into the same database. Ultimately, we collected 443 press releases for this study. A descriptive analysis of these press releases can be found in Table 1 in the results section of this study

Data Analysis

Once we entered each press release’s metadata into the online database and uploaded all text files into the same shared database folder, a qualitative analysis of each press release began, including three rounds of coding. The first round of coding required us to perform simple attribute coding (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014) of the first 10 press releases, producing three attribute codes: gender (as identified through pronoun use), pictures, and videos. The second round of descriptive coding (Miles et al., 2014) required us to evaluate the first 10 press releases separately and then collaborate to compare results. A preliminary list of five variables emerged: 1) mention of one’s educational background (e.g., degrees earned), 2) professional work history (e.g., previous employers, positions held), 3) civic engagement (e.g., membership on a non-profit board of directors), 4) family background (e.g., mention of a spouse, children, or family), and 5) person of the press release (written from the first-person or third-person perspective evidenced by pronoun use). We employed binary and triad coding strategies for the data (1=yes, 0=no; 1=first-person, 3=third-person perspective).

After this first round of coding, performed a third round of inferential coding (Miles et al., 2014) to obtain more insight from the data. comparing results, we producing four inferential codes to describe each press release and its executive leader, including whether the new executive leader was 1) appointed on an interim basis, 2) an internal candidate, 3) an alumnus of the institution, and 4) directly quoted in the text of the press release. We again employed a simple binary coding strategy to code the data (1=yes, 0=no). In all, this three-pronged, collaborative analytic technique yielded three attribute codes (GENDER, PICTURE, VIDEO), five descriptive codes (EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND, WORK HISTORY, CIVIC ENGAGEMENT, FAMILY BACKGROUND, and PERSON), and four inferential codes (INTERIM, INTERNAL, ALUMNI, and DIRECT QUOTE). This resulted in 12 codes to analyze each of the 443 press releases, which produced a total of 5,316 observations.

Limitations

Our coding methods relied on the use of gendered pronouns within the press releases, which does not necessarily reflect a person’s gender identity. We are not making assumptions about a person’s gender based on the pronouns used in a press release; rather, the way a press release is written can speak to the way a person’s gender is assumed by readers. A person’s gender identification (or multiple identifications) may not “line up” with their preferred pronouns—for example, someone may use she/her/hers pronouns and identify as trans* and/or non-binary conforming. In this case, our study would identify the press release as using the pronouns associated with a woman even though the person does not identify this way. Our method may also be flawed if the press release misgendered the president by using nonpreferred pronouns in the press release. Future research could explore whether presidents can control or contribute to the press release announcing their appointment and whether gendered pronouns are assumed by the institution within the release.

This research makes an important and unique contribution to the field of higher education and the analysis of executive leadership at U.S. institutions. However, we acknowledge several limitations of this study, including sample size, the time frame of the data, and analytic technique.

First, this study only captures press releases from 443 U.S. institutions of higher education over a three-year period. Although this sample size is the largest of any analysis of its kind to the researchers’ knowledge, future studies could expand upon this sample size and time frame to provide a more comprehensive and holistic picture of how new executive leaders are introduced to their communities through institutional press releases. In addition, we cannot guarantee that all new executive leaders from late 2016 until early 2019 were included in this study’s sample. As a result, future research could track every executive leader vacancy to ensure that all press releases are analyzed, if such a press release is published by the institution. Furthermore, future research could analyze other forms of institutional press releases, akin to an announcement of the reception of a major gift (Taylor, 2018), to better understand how institutions communicate with their community and the public writ large.

Finally, we delimited this study to a critical discourse analysis (van Dijk, 1993) through a critical feminist lens (Wildman, 2007). Future studies could adopt alternative approaches to analyzing press release data, including computational or corpora approaches that may quantify relationships between new executive leaders and the discourse employed by their institution to communicate their appointment.

Results

A descriptive analysis of press releases included in this study’s sample (n=443) can be found in Table 1.

Across the sample, the largest number of press releases were from private, four-year nonprofit institutions (166 or 37.4% of the sample), followed by public, four-year institutions (136 or 30.6%) and public, two-year institutions (124 or 27.9%). Although the press releases for this study were gathered from several sources, it is notable that few press releases were published by private, for-profit institutions at the two- and four-year level. To our knowledge, there is no theoretical or conceptual basis as to why for-profit institutions may publish these types of announcements less frequently than nonprofit peers, nor is there empirical evidence suggesting sources such as Inside Higher Ed and The Chronicle of Higher Education report on nonprofit institutions more frequently than for-profit institutions. As a result, data in this study suggest for-profit institutions may not report their new leaders in the same ways as their nonprofit peers. This finding represents an area for future research into the marketing and communication differences between nonprofit and for-profit institutions.

Regarding titles and publication dates, the overwhelming majority of press releases announced a new president (396 or 89.3%) than any other executive leadership position (e.g., chancellor, CEO), while press releases were published primarily in 2017 and 2018 given the time frame of data collection for this study (2016-19). However, across nearly three years of press releases announcing new executive leadership at U.S. institutions of higher education, men were appointed executive leaders nearly 25% more frequently than women were, as men comprised 61.3% of the sample whereas women comprised 37.6%. These percentages are similar to recent research from the American Council on Education (ACE) (2019a) that suggested 70% of college and university presidencies were held by men in 2017. Here, data in this study suggests women may be appointed to college and university presidencies in slightly greater numbers than in the past, yet women continue to be underrepresented in new executive leadership announcements in this study.

Finally, administrative units (n=8), presidents/CEOs (n=3), superintendent/presidents (n=5), and press releases written by the new executive leader (n=4, coded as “not disclosed”) represented the smallest percentage of each category of analysis in this study. Although there exist far fewer administrative unit executive leadership positions (e.g., the chancellor of the University of Nebraska System) than single campus executive leadership positions, future research should investigate how administrative unit leaders are introduced to the public through written and spoken rhetoric. Similarly, research could investigate differences between chancellors, presidents, CEOs, and superintendents regarding how these leadership positions are announced to the public and whether job duties, salaries, and professional accomplishments differ from position to position. If differences exist, these research findings could inform the scholarly community as to how different types of executive leaders choose to communicate with the public and how they manage their institutions of higher education.

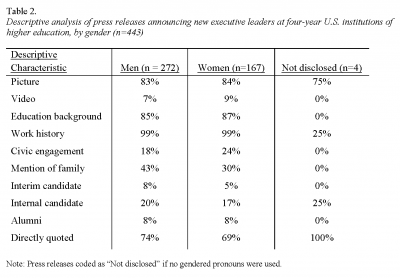

Summary statistics of press releases included in this study’s sample (n=443) can be found in Table 2.

In terms of multimedia, press releases announcing man and woman executive leaders were very similar. For instance, 83% of men and 84% of women press releases included a picture of the person, and women were presented to the public through multimedia in press releases slightly more than men (9% vs. 7%, respectively). The same finding held regarding educational background (85% of men and 87% of women) and work history (99% for both men and women). This signals that across institution types and genders of the new executive leader, institutions of higher education place high importance on sharing a new executive leader’s educational background and work history with the general public and campus community. Subsequently, it may be important to boards of trustees, search committees, and search firms to find new executive leaders who have reputable or newsworthy educational backgrounds and work histories, as these backgrounds and histories will ultimately be shared with the general public and campus community. The implications of this finding will be discussed in a latter section of this study.

Civic engagement and family life were characteristics of departure from the similarities between press releases announcing men and women leaders. Of civic engagement, women (24%) were more likely than men (18%) to have their engagement mentioned in their press release, possibly signaling that women are more likely to be civically engaged with their community than men, or institutional communication professionals felt it more important to mention women’s civic engagement than men’s civic engagement.

Relatedly, men were more likely to have their family life mentioned (43%) than women (30%), possibly signaling that men are more likely to have families than women or institutional communication professionals felt it more important to mention men’s family lives than women’s. Empirical data have suggested that 85% of all college and university presidents are married and another 1% had a domestic partner in 2016 (ACE, 2019a). However, 32% of women presidents have reported altering their career plans and aspirations to care for a family member, including spouses, dependents, children, or others (ACE, 2019b). In this regard, future research should continue to investigate how women leaders are professionally and personally supported throughout the postsecondary leadership pipeline to better understand women’s family lives and whether women are unfairly forced to choose between family and presidency.

Of the college and university leadership pipeline, men were more likely to have been interim presidents (8%) before being appointed to the presidency on a permanent basis than women (5%). Men and women press releases were also similar in terms of being an internal candidate for the presidency (20% of men vs.17% of women) and being an alumnus/a of the institution where they were appointed president (8% of men and women). These percentages have been echoed in extant research, which has suggested 8% of women presidents were interim presidents before being appointed to the position permanently (ACE, 2019b). However, little research has investigated how men and women alumni and internal candidates navigate these positions and reach the college and/or university presidency. Ultimately, the data suggests it was rare for men and women to have their (potentially) interim and alumnus status mentioned in the press release whether by design or oversight.

We analyzed the press releases for quotations from the new presidents to determine if and how the new leaders were given voice in their press release. Men (74%) and women (69%) were directly quoted at similar rates in press releases announcing their executive leadership position. To the researchers’ knowledge, no extant research has addressed what new executive leaders share with the general public or campus community or if gender differences exist between men and women presidents in terms of public speaking opportunities, the publishing of public scholarship (e.g., op-eds), or a president’s willingness to be directly quoted in official, institutional communication. Future research could address how executive leaders share their perspectives and opinions with their campus community and general public, as such perspectives and opinions may help shape the public’s opinion of the president and their effectiveness or transparency as the most powerful leader of an institution of higher education.

Finally, this study did not yield a single press release announcing a new executive leader who identifies as non-binary conforming. As discussed earlier, we recognize that pronoun use does not necessarily correlate with gender. In addition, this method may be flawed if the college or university misgendered the president by using nonpreferred pronouns in the press release. No press releases in this study used third-person pronouns (they/them/theirs) or other forms of non-gendered pronouns. Although little research has addressed the pathways to and experiences in the presidency of non-binary conforming individuals, future research could address how non-binary conforming individuals have been historically excluded from executive leadership positions, touched upon by prior work (Renn, 2010).

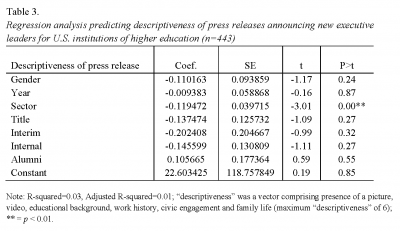

A regression analysis predicting the descriptiveness of press releases included in this study’s sample (n=443) can be found in Table 3.

As a vector variable containing six descriptive characteristics of press releases (picture, video, educational background, work history, civic engagement, and family life), a regression analysis only institutional sector was predictive of descriptiveness (p < 0.01), whereas the gender of the newly appointed executive leader was not. Before running the regression analysis, we ran a two-way ANOVA to explore whether men and women press releases were more descriptive using the same vector variable to calculate descriptiveness: These results were not statistically significant.

However, supporting the descriptive statistics of this study (Table 1), there were markedly more public two- and four-year institutions as well as private, four-year nonprofit institutions than for-profit institutions. As data were coded 0=administrative units, 1=public, two-year institutions, and so on, the regression analysis indicated public institutions were more likely to publish more descriptive press releases announcing new executive leaders than private for-profit and nonprofit peers. Perhaps public institutions and their marketing and communications teams felt the responsibility to serve the public and provide a wealth of detail regarding the institution’s new president, a responsibility that perhaps private institutions did not feel. Future research could address differences in communication habits between public and private institutions, paying special attention to what public and private institutions choose to publicize and what details are included in this publicity.

Discussion and Implications

Our findings show that across nearly three years of press releases, men were appointed to executive leadership positions nearly 25% more frequently than women (61.3% of the sample vs. 37.3%). These results are consistent with the recent research from the American Council on Education (2019a, 2019b) that found roughly 70% of college and university presidencies were held by men in 2016 and 2017. ACE data suggests that women are being appointed to college and university presidencies in slightly greater numbers, yet continue to be underrepresented as demonstrated by our findings.

One result of this study was the large number of press releases that mentioned the educational background (85% for men and 87% for women) and work history (99% for both) of new appointees. This suggests that these areas are of utmost importance to boards of trustees, search committees, and search firms when screening and selecting an executive leader. Reasons may include validating the new hire based on education and experience, elevating prestige in previous positions or institutions, or simply listing categories that are perceived as important to the public. Here, future research should continue to investigate how boards of trustees, search committees, and search firms select presidential candidates, paying close attention to how candidates are assessed and their credentials shared depending on their gender.

In this study, where press releases differed by gender, data suggests male executive leaders have their family lives shared with the public (43%) more frequently than women executive leaders (30%). Although future qualitative analyses should continue to investigate how women and non-binary conforming individuals rise among the ranks and achieve positions of power and authority, it is equally important to investigate the institutional rhetoric surrounding these positions of power. We do not know if the women presidents in this sample had families or not, but longitudinal research has demonstrated that women are often forced into compromising their professional careers for the sake of their families and loved ones (ACE, 2019a, 2019b). Nearly every person has a family or personal network, yet the institutional rhetoric of the press releases in this study suggest male presidents have families—or their institutions valued their families and shared them with the public—more frequently than women presidents’ families. Extant research showed that women are often excluded from leadership positions because of society’s stereotypical and masculine image of leadership (Beck, 2003; Hill et al., 2016).

van Dijk (1993) and Wildman (2007) would argue that disparities in how men and women leaders are portrayed in media—such as press releases—harmfully reinforce and maintain gender stereotypes and extant, masculine leadership structures. From here, critical feminist research and educational research in general ought to investigate how men, women, and non-binary conforming leaders are portrayed in media, paying close attention to how one’s personal and professional story is told.

The results of this study also suggest that for-profit institutions may not report on the appointment of new presidents or chancellors at the same rate as their nonprofit peers. Since this study exclusively examined press releases, and not positions that were filled but not announced, it is unclear if the turnover rate at for-profit institutions is lower than nonprofit ones or if the announcement and reporting is simply different. Subsequently, future research should examine the marketing and communication differences between nonprofit and for-profit institutions, considering how influential presidents can be and how communication of new presidencies may influence the public’s and campus community’s perception of the incoming leader.

Another area for future research is investigating how administrative unit leaders are introduced to the public and higher education community through written and spoken discourse. Similarly, research could investigate the differences in how new chancellors, presidents, CEOs, and superintendents are announced, and whether their job duties, salaries, and professional accomplishments differ depending on the position and the gender of the candidate. Although this study analyzed few announcements of administrative unit leaders, educational researchers should continue to investigate how men, women, and non-binary conforming individuals navigate careers in educational leadership and achieve positions of power and authority, especially as women and non-binary conforming individuals have been excluded and marginalized from these positions of power. van Dijk (1993) asserts that power and positions of power can be codified and reinforced through written and spoken rhetoric. Thus, research must continue to interrogate the role of institutional communication regarding the appointment of women and non-binary conforming individuals to positions of power, as the written and spoken rhetoric surrounding those positions–such as press releases–may communicate possible pathways to executive leadership for other marginalized individuals to follow.

Conclusion

Consistent with findings in the ACE study (2019a, 2019b), our results show that women continue to be underrepresented in executive leadership positions in higher education. Despite advances in increasing diversity on campus, the positions of college president and chancellor continue to be dominated by men. For those women who are appointed in these executive positions, the vast majority (92%) are at non-doctoral-granting institutions (ACE, 2019b), resulting in men holding an unequal share of the executive leadership power structure in U.S. higher education.

Appointment announcements about the new executive leader almost always include details about previous work history and educational background. However, men were more likely to have their family detailed in the press release than women (43% vs. 30%). Men were also more likely to be internal or interim candidates, or alumni of the institution. Future research is needed to further explore these findings and the implications they have on the field of U.S. higher education, including how women and non-binary conforming individuals can transcend extant power structures and lead institutions of higher education into the future.

Historically, descriptions of past executive leaders have been “infused with stereotypically masculine traits: aggression, decisiveness, willingness to engage in conflict, strength, and so on” (Hill et al., 2016, p. 5). Researchers and advocates must consider this a call to dismantle this leadership structure and facilitate a clearer, more equitable path to executive leadership for those who have been historically underrepresented and marginalized. This includes a critical, feminist questioning of “who did they just hire?” not only on the basis of gender, but on how those leadership positions are communicated by gender. Otherwise, institutional rhetoric may continue to support historically oppressive power structures in U.S. higher education, rendering the field a much less equitable and just one.

References

American Association of University Women. (2016). Barriers and bias: The status of women in leadership. Retrieved from https://www.aauw.org/research/barriers-and-bias/

American Council on Education [ACE]. (2019a). American college president study 2017: Summary profile. Retrieved from https://www.aceacps.org/summary-profile/#demographics

American Council on Education [ACE]. (2019b). American college president study 2017: Women presidents. Retrieved from https://www.aceacps.org/women-presidents/

Ballenger, J. (2010). Women’s access to higher education leadership: Cultural and structural barriers. Forum on Public Policy Online, 2010(5), 1–20. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ913023

Beck, A. J. (2003). Through the looking glass-ceiling: The advancement of women administrators and women faculty in an institution of higher education (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX.

Brown, T. M. (2005). Mentorship and the female college president. Sex Roles, 52(9, 10), 659-666. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-3733-7

Chisholm-Burns, M. A., Spivey, C. A., Hagemann, T., & Josephson, M. A. (2017). Women in leadership and the bewildering glass ceiling. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 74(5), 312–324. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160930

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810.

Davis, D. R., & Maldonado, C. (2015). Shattering the glass ceiling: The leadership development of African American women in higher education. Advancing Women in Leadership, 35, 48–64.

Graham, P. A. (1978). Expansion and exclusion: A history of women in American higher education. Signs: A Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 3(4), 759–773. doi: 10.1086/493536

Greenhaus, J. H., & Parasuraman, S. (1999). Research on work, family, and gender: Current status and future direction. In G. N. Powell (Ed.), Handbook of gender and work (pp. 391–412). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hannum, K. M., Muhly, S. M., Shockley-Zalabak, P. S. & White, J. S. (2014). Women leaders within higher education in the United States: Supports, barriers, and experiences of being a senior leader. Advancing Women in Leadership, 35, 65–75.

Hopkins, P. [peterhopkins]. (2018, April 22). What is intersectionality? [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/O1islM0ytkE

Jablonski, M. (1996). The leadership challenge for women college presidents. Initiatives, 57(4), 1–10.

June, A. W. (2007, February). Presidents: Same look, different decade. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 53(24), 33–40. Retrieved from https://chronicle.com

Koenig, A. M., Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Ristikari, T. (2011). Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 616–642. doi: 10.1037/a0023557

Lederman, D. (2019, February 22). New presidents or provosts: Allegheny College, Georgia Southern U, Grand Valley State U, Grande Prairie Regional College, Liberty U, Queens U (NC), Temple U Rome, Tufts U, U of Hawaii at Hilo. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com

Longman, K. A., & Lafreniere, S. L. (2012). Moving beyond the stained glass ceiling: Preparing women for leadership in faith-based higher education. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 14(1), 45–61. doi: 10.1177/1523422311427429

Lyness, K. S., & Grotto, A. R. (2018). Women and leadership in the United States: Are we closing the gender gap? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 227–265, doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104739

Madsen, S. R. (2008). On becoming a woman leader: Learning from the experiences of university presidents. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Moody, J. (2018, July 5). Where are all the female college presidents? Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com

Muñoz, M. (2009). In their own words and by the numbers: A mixed-methods study of Latina community college presidents. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34(1, 2), 153–174. doi: 10.1080/10668920903385939

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). IPEDS: Integrated postsecondary education data system, use the data. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data

Oikelome, G. (2017). Pathway to the president: The perceived impact of identity structures on the journey experiences of women college presidents. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(3), 23–40. doi: 10.18251/ijme.v19i3.1377

Piper, J. (2019, February 28). Transitions: Norfolk State U. selects new leader, Bucknell U. names provost. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com

Ramos, S. M. (2008). Latina presidents and four-year institutions, penetrating the adobe ceiling: A critical view (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ). Retrieved from The University of Arizona Repository. (659750807).

Renn, K. A. (2010). LGBT and queer research in higher education: The state and status of the field. Educational Researcher, 39(2), 132–141. doi: 10.3102/0013189X10362579

Sanchez-Hucles, J. V., & Davis, D. D. (2010). Women and women of color in leadership: Complexity, identity, and intersectionality. American Psychologist, 65(3), 171–181. doi: 10.1037/a0017459

Stout-Stewart, S. (2005). Female community-college presidents: Effective leadership patterns and behaviors. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 29(4), 30–35.

Taylor, Z. W. (2018). Go big and go home: Major gifts, public flagships, and the parlance of prestige. Philanthropy & Education, 1(2), 54–81. doi:10.2979/phileduc.1.2.03

Tunheim, K., McLean, G., & Goldschmidt, A. (2015). Women presidents in higher education: How they experience their calling. Intersections, 2015(42), 30–35. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/

van Dijk, T. A. 03–315. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249–283. doi: 10.1177/0957926593004002006

Waring, A. L. (2003). African-American female college presidents: Self conceptions of leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(3), 31–44. doi: 10.1177/107179190300900305

Wheat, C. A., & Hill, L. H. (2016). Leadership identities, styles, and practices of women university administrators and presidents. Research in the Schools, 23(2), 1–16. Retrieved from http://www.msera.org/publications-rits.html

Wildman, S. M. (2007). Critical feminist theory. In D. Clark (Ed.), Encyclopedia of law & society: American and global perspectives (Vol. 1, pp. 349–350). doi: 10.4135/9781412952637.n150

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of press releases announcing new executive leaders for U.S. institutions of higher education, by institution type, executive leader title, year, and gender (n=443)

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of press releases announcing new executive leaders at four-year U.S. institutions of higher education, by gender (n=443)

Table 3. Regression analysis predicting descriptiveness of press releases announcing new executive leaders for U.S. institutions of higher education (n=443)