Community Builders and Campus Bureaucrats: Student Leadership on College Campuses

J. Douglas Stump

St. Bonaventure University

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Dr. J. Douglas Stump, School of Education, St. Bonaventure University, dstump@sbu.edu

Abstract

Most universities provide many opportunities for students to be leaders. By placing students in these positions there exists the potential to create a unique set of challenges. This research focused on the challenges associated with leading peers on a university campus. The primary research question was, “In what ways are student leaders able to identify and describe their experiences leading their peers?” This was a case study, collecting data through focus groups and interviews, where participants discussed the experiences of leading peers. Four types of student leaders participated: Sports Team Captains, Resident Assistants, Academic Mentors and SGA Officers. The data revealed that these groups of leaders aligned into two categories: Community Builders and Campus Bureaucrats.

Most universities provide many opportunities for students to be leaders (Planety, Hussar, Snyder, Provasnik, Kena, Dinkes, KewalRamani, & Kemp, 2008). Students are asked to be team captains, residence hall assistants and officers of student organizations. They are expected to manage buildings, direct bands, be in charge of equipment and direct other student workers. On any given campus most departments have students performing some function of leadership, and these positions provide valuable experiences for students as part of co-curricular learning. Offering students leadership opportunities can positively influence the development of leadership qualities that serve students post-graduation (Dugan & Komives, 2007). Although leadership development is the primary purpose for providing students with access to leadership positions, placing students in these types of positions may create a unique set of challenges. The problem this paper addresses is that although research exists on the benefits of student peer leadership, there does not seem to exist a deep understanding of what students experience when placed in positions of student peer leadership.

Defining Student Leadership

The label of student leadership is broad, and there is a variety of both leadership work and the methods of assignment of such work. Most student leadership positions seem to be defined by the tasks performed. Kotter (2011) distinguished between leadership and management, providing one way to consider how to define the work of student leaders. Leadership, as Kotter (2011) describes, is distinct and set apart from the task of management. Leadership is about movement, in that it establishes direction, it aligns people, it motivates and inspires, and produces change (Kotter,2011). Conversely, management is used to bring order to an organization or a process (Kotter, 2011). Management is about ordering the processes of an organization so that goals can be met on time and on budget, which is different than leadership. If we use Kotter’s (2011) definitions and apply them to the many tasks performed by student leaders, one could argue that students employed as leaders are performing more managerial responsibilities than leadership tasks. For example, resident assistants and building supervisors manage forms, communication, and building use policies; band leaders coordinate practice schedules and membership policies; and club officers tend to agendas and events. For the purposes of this study, Student Peer Leader is defined as a student who, through positional authority, holds some measure of authority over peer students to enforce rules and set boundaries. For this study, student leadership is defined as a wide range of positions to which students are assigned where they are in authority over their peers in some capacity, and authority refers to positional authority. The participants selected for this study held positions identified as a Student Peer Leader positions.

Research Question

This study posed the question, “What are the experiences of peer leadership for students of higher education institutions?

Background of the Study

Student Leaders, Social Structure and University Culture

This study addresses the problem of the types of challenges college students, assigned to leadership positions, encounter when leading their peers. One way to better understand the phenomenon of the challenges of peer leadership for college students may be through theories of social structure and social capital.

Merton’s (2013) writing on the concept of social structure provides a theoretical basis for understanding the common behaviors of students when assigned to roles of leadership. He stated that each group has culturally defined goals and interests, and these goals are viewed as legitimate interests for all members of the culture (Merton, 2013). The structure of the culture establishes and regulates the ways in which members of a group reach those goals or experience interests. Each social group pairs cultural goals with acceptable means of reaching those goals (Merton, 2013). Merton’s (2013) work provides one explanation for how students may formalize an understanding of their assigned leadership roles in the absence of formal training.

Student leaders are assigned leadership positions, including team captains, who are selected by coaches; resident hall assistants (RAs) and building supervisors, who are hired by professional staff; performance group leaders, who are selected by faculty; club officers, who are often appointed or elected by members of the group. Students may express interest in leadership opportunities through either a formal or informal application process, but the positions themselves are given based on assignment. However, with most student leadership positions, there is no formal training for what it means to lead peers. Students may receive some formal instruction with regard to tasks that come along with the leadership positions. For example, an RA will receive training on recognizing students who are in need of intervention and what the regulations are for residence hall students. However, there is no formal induction for student leaders for navigating the positions of authority over and with their peers. Team captains, for example, are not instructed on how to engage team members, motivate them, or discipline them. Club officers are not provided direct instruction on how best to engage club members to accomplish tasks.

Without any formal induction process for student leaders, it is possible that the culture of the position to which they have been assigned has an existing structure by which students adopt culturally defined goals and modes of reaching those goals. As Merton (2013) described, social structure exerts pressure upon members of the society to work toward acceptable goals in acceptable ways. Based on Merton’s (2013) ideas, the construct of team captain, which a team member might have come to know informally through exposure to the culture of team sports, would be assumed along with the appointment of the title. The concept that Merton (2013) refers to as cultural structure may create a shared expectation of what it means to be set apart as a student leader. This process of assuming a culturally supported understanding of leadership in the absence of a formal induction is one challenge unique to the experiences of student leaders.

These ideas of cultural membership are especially true for college campuses because even though an entire campus can be considered a singular culture, many social groups exist within the broad campus culture. For example, a student who is a team captain and member of an athletic group, will also attend class in an academic group, perform with a musical troupe in a conservatory group, live in a residence hall in an on-campus housing group, and may participate in a business major fraternity as a member of a social group. Each group may possess aspects of culture unique to the community. These micro-communities or social groups will have established norms, expectations, and understandings of what it means to belong. Part of the experience for a college student is to move from one micro-group to the next, and often making several movements in the span of one day, which is also part of the adaptation that occurs once they are members of the college community is navigating the change between these micro-social groups.

Relationship Between Institutions and Student Leadership

Some studies address the relationship between higher education institutions and student leadership. One such study by Shook (2011) considers the need universities may have to rely on student leaders to meet the work demands of academic and support offices. Shook asserts that greater demand on student affairs offices and financial constraints have led to the rise in some student leader positions. This rationale for providing peer leader positions for students seems to contrast other work such as a study by Campbell, Smith, Dugan, Komives (2012), where the researchers identify a rationale for why universities provide leadership learning as developmental and educational. This study suggests universities may be providing co-curricular leadership opportunities as response to the increased awareness of a need for leadership and the awareness of the gap between leadership needs and perceptions of leadership capacity. Where Dugan and Komives (2007) and others offer rationales for peer leader positions as co-curricular leadership learning, Shook’s (2011) study offers the perspective that these peer leader opportunities provide for a practical, financial need for universities. This study does not address any co-curricular benefits for student leaders, but does address processes for hiring and staffing using student leaders.

Methods

This was a basic field study, collecting data through focus groups and interviews, in which student leader participants discussed the experiences of leading peers. Focus groups and interviews also provided the opportunity for participants to hear, reflect and respond to what other student leaders say about their experiences. For the researcher, this interaction provided a way of understanding the participants’ experiences.

Site Selection, Strategy and Procedures for Focus Groups

This case study was conducted at one small private college in the mid-Atlantic region. The institution was selected because it provides traditional student leadership opportunities and the geographic location was convenient for the researcher. Further, a small private school was a good fit for this study because with a small school the possibility existed that there may be a good number of students involved in more than one leadership role.

The site selection and sampling used for this study were strategic and purposive. As a collection site for this study, the school used was selected based in part on the site’s size – the researcher focused on small institutions based on the limited scope of the study – and in part because the site school agreed to participate. For this reason, convenience was also a sampling factor. The selection of participants was theoretically driven, in that participants were selected based on the kind of peer leadership work performed. As a result, four homogeneous groups of participants were formed (Miles, Huberman & Saldana, 2014), which were Resident Assistants (RAs), Sports Team Captains, Academic Mentors and SGA Officers. Participants were selected for the interviews as students who serve in the same kinds of roles represented in the focus groups but who did not participate in the focus groups. The four focus groups had between six and eight student leaders participating in each group.

The researcher began each focus group with scripted questions about the general experiences as student leaders. Initial questions for data gathering included, “What is it like serving as a student leader?”, “In what ways would you consider your position on campus to be leadership?”, “What responsibilities do you have?” , “What is it like to be in leadership in one area of campus but not in leadership in other areas?, and “How do you balance your leadership work with your own student demands?”

From these initial questions, other questions were developed based on the responses of the participants. For example, after students identified leadership positions they held prior to college, I followed with, “Can you describe your duties in these roles,” and “Are there similarities between your leader work before entering college and the leader work you are doing now?”

Interviews were also conducted as a second data source. Participants were selected in the same way students were selected for the focus groups, with the difference being that the interviews were with just one student at a time. The researcher conducted one interview for each of the four types of student leader roles represented in the focus groups –Resident Assistant, Sports Team Captain, Academic Mentor and SGA Officer. The questions used during the interviews included questions such as, “In your role as student leader, describe any sense of expectation you feel to be a model student for those you lead?” “In what way, if at all, would you identify your experience as a college student as being an attribute of your leadership?” and “ Do you feel that your work as a student leader is a 24/7 job?”

Data Analysis: Focus Groups and Interviews

After the group sessions were transcribed, the researcher began the coding process. Initial analysis of the transcribed focused groups was designed to identify common language used by participants to describe their views of leadership work and the ways in which the challenges of student leadership was articulated. The researcher used in vivo coding (Saldana, 2016, p. 105). Initial analysis of the transcribed focused groups was designed to identify common language used by participants to describe their views of leadership work and the ways in which the challenges of student leadership was articulated.

Trustworthiness and Generalizability

To address the question of credibility, this research design relied on the researcher’s interpretation of the participants’ data. Analysis of the data is at risk of some researcher bias due to the researcher’s personal analysis of the data and what constitutes data from the transcripts. The researcher’s own professional background may create a second bias through which the data will be interpreted. To address credibility, member checks were used (Creswell, 2014), which were also used to address internal validity. After the focus group sessions were transcribed, the researcher asked selected participants to provide reactions regarding how the material is captured. To address reliability, the researcher maintained an audit trail (Creswell, 2014), which also addressed to some degree the dependability of the results. To address external validity, which is the extent to which the findings of this study can be generalized or applied to other contexts, the researcher selected participants that represented groups beyond the collection site. The students were enrolled as full-time undergraduate students, and the participants held positions of leadership compared to other institutions.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that based on the perceived relationship between the researcher and the campus contact, participants may not have felt at liberty to be candid or open to speaking freely. There is no way to eliminate this bias, but through the Informed Consent the researcher defined how the data will be used and define the barriers between the researcher and the professional staff on campus.

Results

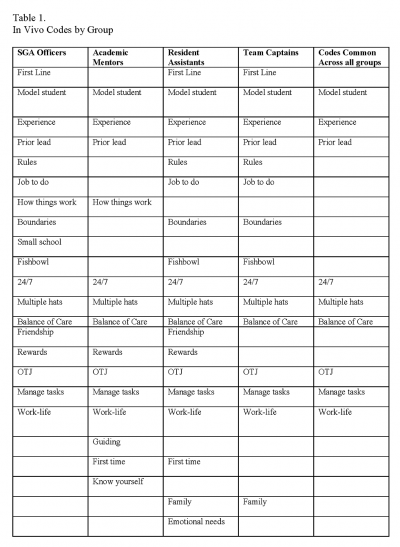

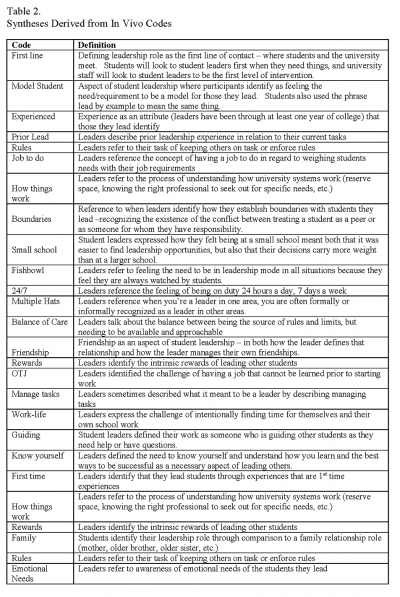

Through the analysis of the transcripts, participants described their experiences that were captured with 26 distinct codes. These codes are separated by the type of student leader group (see Table 1), and the researcher provided syntheses for each code (Table 2).

Through the analysis of these codes, two different groups of leaders emerged, Community Builders and Campus Bureaucrats.

Community Builders — Resident Assistants and Sports Team Captains

RAs and Sports Team Captains were two groups that talked about their work in terms of both leadership techniques and tasks. In both groups, some students did discuss the task management part of the work. For RAs, this may be completing forms or serving hall duty, and for Sports Team Captains this may be organizing practice and running drills. When asked what it was like to be a peer leader, there was uniformity in how the participants identified what they did as RA’s and Captains as being in leadership. The participants responded to that question not by listing the tasks associated with the job, but rather how they were leading a group of often younger students and modeling for them how to be successful.

Resident Assistants spent a lot of time discussing the codes Model Student (participants felt the need to be a model for those they led in conduct and performance), Boundaries (the challenge of establishing boundaries with students and acknowledging the conflict between treating a student as a peer and as someone for whom you have responsibility), Balance of Care (the challenge of being both the source of rules and limits and also needing to be available and approachable), Family (using family identifiers such as mother, father, brother or sister as ways to identify leader work), and First Line (defining leadership work as the place where students and the university meet -student leaders are the first line of contact for other students). All of these codes represented aspects of traditional leading rather than task completion. When discussing expectations of their work, both RAs and Sports Team Captains used the code Model Student. Gary (participants’ names have been changed) described this sense of expectation when he said, “your residents look up to you, a model student.”

Brenda commented that, “yeah, you’re someone who has been there before and has experience.” Maddie commented, “model student – you are leading by example.” When asked to explain more, Maddie said, “when freshmen come in they automatically kind of look up to you because you’ve been there before.” Kurt said, “I always hold myself to really high standards so I’m not going to try and be a bad role model, it’s like Gary said, we’re model students.”

Chris said,

Just being a captain on the field is also kind of being a captain off the field because we’re held to a higher standard by coach and also by the other players, so we have to exceed all expectations on and off the field.

Jason followed that comment with, “the freshmen normally look up to us for, they kind of look for us to advice and stuff, it’s a respect thing, so we have to live up to that.”

Participants articulated a feeling that they see themselves positioned between students and the university staff, which became the code First Line. Maddie said, “because we’re on the halls, we are the first line of defense.” When asked to clarify, she said, “the job is kind of like peer advisor, because we live together, you’re (we are) the first line of contact.”

Jason commented that,

As team captain I am the meeting, the in-between stage of coaches and players, if they have a topic they need to discuss or they have a problem they normally come address me or one of the other captains, depending on the situation we’ll take care of it, so we keep coach out of it. We only bring coach in on important stuff.

Stacy said,

As captain, you’re trying to look over 23 other girls just to make sure – the freshmen coming in feel welcome. It’s all just outside of the sport. You’re trying to be their best friend at the same time, but they also need to respect you, so you are that balance – you have the coaching staff, but then the coaching staff depend on you as captain, but you also need to be like your teammates as well.

In both groups what is similar is that they are both organic communities. Sports teams represent a community or small group within a campus community. Resident Assistants work in residential communities. In both cases, these communities exist naturally as part of campus life. In both cases, the leaders of the groups work as community builders, a leadership role where expectations of the group are identified and expressed, and the leaders work to support the group. In both cases, Sports Team Captains and Resident Assistants would have experienced some form of induction into their groups as new team members or freshmen living in new residence communities. These experiences may have been the leadership induction that helped create the leader expectations for them in the work they currently perform.

Campus Bureaucrats – Academic Mentors and SGA Officers

The other two groups of student leaders – Academic Mentors and SGA Officers – both discussed their jobs in similar terms, as well. In both cases, the participants did not discuss their jobs in terms of leadership but rather in terms of task management. When asked to talk about how their jobs reflected peer leadership, SGA Officers talked first about scheduling and running meetings, connecting students with ideas to the on-campus funding for events, and helping club members navigate the campus bureaucracy. Academic Mentors discussed the tasks associated with helping other students and mentoring first year programs. Codes frequent in the discussions with these two groups include First Line (defining leadership work as the place where students and the university meet -student leaders are the first line of contact for other students), How Things Work (the process of understanding how university systems work, such as reserving space on campus and knowing which professional staff to go to for specific needs), and Rules (the challenge of keeping others on task and enforcing rules). This is evident in how each of these two groups discussed the code How Things Work. SGA Officers discussed knowing how to manage an event to receive funding and support, for example. Academic Mentors discussed knowing how to connect students with resources.

Barry was the first in the SGA Officers group to discuss the code How Things Work when he said, “I think more of my problems was just learning the role and understanding how things work, and how to get things done, how best to use the resources.” When I asked him to elaborate, he said, “that’s what the job is, really. If a student comes to you and says we want to have this event, you know who to talk to and how to ask for funds, and so you spend your time connecting people and setting stuff up.”

Jay agreed with Barry, and added, “it’s about getting things done, and you have to know how it all works.” Roberto added,

The one word that comes up a lot is self-initiative. The SGA talks a lot about do something, don’t just expect me to do it. If you want something, if you have passion, if you want an event, you can go ahead and do it. You can ask me and I help because I know all the right channels.

Kotter (2011) describes leadership as distinct and set apart from task management. In the case of Campus Bureaucrats, it appears we have a group of student leaders that perform primarily managerial tasks but who have adopted an understanding of the work as leader work. This may be attributed to how the campus community outwardly presents and defines these positions. The convergence of Kotter’s (2011) work and the concept of Campus Bureaucrats as a way of categorizing SGA Officers and Academic Mentors yields several follow up questions. If certain groups of student leaders are identifying their work as leadership when it is actually task management, does this reinforce a misunderstanding of leadership for the students working as Campus Bureaucrats? If so, what are the implications for universities to differentiate through title and description student campus work? Is there an advantage in recruiting, for example, if a position is referred to as peer leadership, even when the task is not leadership? A second issue is that of positional authority. In the case of the Campus Bureaucrat, these student leaders tended to define peer leadership through the lens of task management. Even if what these participants described was management, they used the term leader when referring to their work. It is possible that the students within the student body view these positions as peer leadership positions, as well. Without any other form of differentiation, does the campus student community hold Campus Bureaucrats as peer leaders through positional authority and thus place the same expectations on Campus Bureaucrats as students would on Community Builders? It is possible that the students within the student body view these positions as peer leadership positions, as well.

Discussion

In addition to the research questions, two observations about the peer leadership experience became evident through studying the findings. First, that there was no uniform understanding of what peer leadership meant or what leadership as a construct represented. As mentioned earlier, tasks alone do not define student leadership positions. Student leaders are set apart from their peers through positional authority, which means students may, by position and title, be viewed as leaders regardless of the tasks performed.

Participants in this study seemed to define leadership by their position title and tasks associated with their jobs, but not all shared an awareness that those titles or position descriptions defined them as leaders. For two groups in particular – Academic Mentors and SGA Officers – this was especially true. For Academic Mentors, for example, when asked to define peer leadership or describe what peer leadership means, participants answered with descriptions of tutoring others or providing academic support. SGA officers discussed tasks such as being good at email communication, navigating campus offices to find support for student events, and managing meetings. The two other groups – RAs and Sports Team Captains – also articulated leadership in terms of tasks, but also expressed some awareness of what leadership means in addition to just task management.

Another observation from this study was the lack of leadership induction for the participants. In describing leadership training, all the participants discussed task or managerial training as their only induction into their peer leader roles. With the Sports Team Captains, some participants articulated that they received no training or explanation of expectations. In observing the disconnection among the various groups about how participants both understood their work as it relates to the idea of peer leader and was inducted into leader work, one takeaway is that one size does not fit all with regard to leadership understanding or leadership induction. Rather, the idea about what leadership is and what leader work looks like is germane to the kind of leadership role to which a student is assigned. For this study, two groups emerged with different understandings about leader work – Community Builders and Campus Bureaucrats.

University Presidents and Student Leadership Positions

For university presidents, the findings in this study may resonate through answering several critical questions. First, how is student leadership used on my campus? As evident in the literature, student leadership can provide co-curricular learning opportunities for students, but it may be helpful to dig a little deeper to understand the culture around student leadership on an individual campus. Questions for college presidents to consider when evaluating how leadership is used would be, “To what extend is there a way to formally capture learning outcomes for student leaders?”, “Do all student leadership positions on my campus have a connection to some kind of leadership learning through a leadership program, work study, or career services?”, and based on answers to these questions, “Would a more clearly defined leader development program increase student retention and performance?”.

Connected to this idea of potent leader programs is leadership induction. Based on the findings in this study, the concept and understanding of leadership appear to be germane to the kind of leadership role a student is assigned. That means that perhaps leader induction and leadership training based on the community in which the student is assigned a leadership role. Stated another way, universities may want to avoid investing in a one-size-fits-all leadership induction workshop. However, the findings in this study do provide a way of knowing what challenges leaders may experience, and this may be particularly helpful for university presidents in deciding where to strategically house student leadership programs and who participates in the training, induction, and evaluation process.

Lastly, this study may resonate with university presidents in understanding the functions student leadership fulfill on a specific campus. As some research suggests, as funding for professional campus staff positions grows more scarce, student leadership positions may be filling the gap by providing ground-level campus staff work through the creation of more and more student leadership jobs. If that’s the case, a reasonable question would then be, “How does the university invest in knowing if this is a function of student leadership on the campus, and if the answer is yes, should a more formal approach be used to define student leadership positions, training and outcomes?”. Just as universities may be finding more reasons to provide student leadership positions, students may be seeking more co-curricular ways to learn job skills while pursuing a degree.

Follow up from this study can take many forms, but through current literature it seems that the topics of peer leadership – the usefulness of peer leadership for institutions, the value of peer leadership for participants in post-graduate success and the ways in which peer leaders identify themselves as leaders, among others – continue to be an integral part of both university programming and student life experiences. Understanding in concrete ways what students experience as peer leaders is one step toward more potent and meaningful leader work.

References

Bolden, R. (2011). Distributed leadership in organizations: A review of theory and research. International Journal of Management Reviews (13)3, 251-269.

Brungardt, C. (1996). The making of leaders: A review of the research in leadership development and education. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(3), 81-95.

Campbell, C. M., Smith, M., Dugan, J. P., & Komives, S. R. (2012). Mentors and college student leadership outcomes: The importance of position and process. The Review of Higher Education, 35(4), 595–625.

Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95-S120.

Day, D., Harrison, M. M. & Halpin, S. M. (2009). An integrative approach to leader development: Connecting adult development, identity and expertise. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dugan, J. P. & Komives, S. K. (2007) Developing leadership capacity in college students: Findings from a national study (report from the Multi-Institutional Study of Leadership). College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Friedel, C., Church, K. K. & Grimes, M. (2016). Principles of peer leadership: An undergraduate course for students in positions to serve fellow students. The Journal of Leadership Education (15)2, 38-47.

Glense, C. (2016) Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (5th Ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Gliner, J. A., Morgan, G. A., & Leech, N. L. (2009). Research methods in applied settings: An integrated approach to design and analysis. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gutierrez, K., & Correa-Chavez, M. (2006). What to do about culture?. Lifelong Learning in Europe, 11 (3), 152-159.

Higher Education Research Institute (1996). A social change model of leadership development: Guidebook version III. College Park, MD: National Clearinghouse for Leadership Programs.

Kolb, D. A. (1981). Learning styles and disciplinary differences. In A.W. Chickering and Associates (Eds.), The modern American college: Responding to the new realities of diverse students and a changing society (pp. 232-255). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S., Owen, J., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2006). A leadership identity development model: Applications from a grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4), 401-418.

Komives, S. R., Lucas, N., & McMahon, T. R. (2007). Exploring leadership: For college students who want to make a difference. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Komives, S. R., Owen, J. E., Longerbeam, S. D., Mainella, F. C. & Osteen, L. (2005). Developing a leadership identity: a grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 46, 593-611.

Kotter, J. P. (2011). Management and Leadership. In W. E. Natemeyer and P. Hersey (eds.), Classics of organizational behavior (4th) (pp. 360-373). Longrove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Lee, C. (2008). The centrality of culture to the scientific study of learning and development: How an ecological framework in education research facilitates civic responsibility. Educational Researcher, 37 (5), 267-279.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: an interactive approach (3rd ed.) Los Angeles: Sage.

Merton, R. (2013). Social structure and anomie. In C. Lemert (Ed.) Social theory (5th ed.) (pp. 174-183). Boulder: Westview Press.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Planety, M., Hussar, W., Snyder, T., Provasnik, S., Kena, G., Dinkes, R., KewalRamani, A., & Kemp, J. (2008) The condition of education, 2008. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Shook, J. L., & Keup, J. R. (2012). The benefits of peer leader programs: An overview from the literature. New directions for higher education No. 157 (pp. 5-16). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Whitney, R., Early, S., & Whisler, T. (2016). Create a better flow through sequencing resident assistant training. The Journal of College and University Student Housing, 43(1), 28-43.

Wooten, B., Hunt, J., LeDuc, B., & Poskus, P. (2012). Peer leadership in the co-curriculum: Turning campus activities into an educationally purposeful enterprise. New directions for higher education No.157, (pp. 45-58).

Table 1. In Vivo Codes by Group

Table 2. Syntheses Derived from In Vivo Codes