Perspectives on Time Commitment to Fundraising by Community College Presidents

G. David Gearhart

University of Arkansas

Michael T. Miller

University of Arkansas

Correspondence related to this article should be addressed to Dr. G. David Gearhart, Chancellor Emeritus and Professor of Higher Education, University of Arkansas, gdgearh@uark.edu

Abstract

All types of higher education institutions have come to rely on some element of revenue diversification, and fundraising from private sources has become increasingly common and popular among community college presidents. Yet despite the growth in attention to fundraising, community colleges collectively only garner 2% of all philanthropic support to higher education. With the growing demand for private funds, community college presidents must understand how they are using their time for fundraising, and ultimately, the consequence of these fundraising efforts. The current study explored the time commitment of college presidents, finding that they spend as much as 30% of their workplace time each month on development related activities.

One of the critical roles of the contemporary community college president is the pursuit of revenue streams that add to the financial health of an institution (Goddard, 2009). Leadership in seeking revenue might include partnerships with industry, legislative relations, grant writing, and increasingly, includes the process of fundraising from private sources. Despite this importance, community college fundraising accounts for only about 2% of all philanthropic support for higher education, despite its enrollment of approximately half of all higher education students (Gyllin, 2013).

Community college fundraising has typically occurred in the realm of business and industry partnership, where focused grants are given to an institution to facilitate some type of training program. This might be, for example, the donation of a diesel engine to teach engine repair, or the funds necessary to build a loading dock to be used with truck driver training. Increasingly, though, as community colleges look to expand their academic offerings, gifts mirror those of four-year institutions and include endowed scholarships, named facilities, and unrestricted funds to help the institution operate.

This pressure to identify and secure resources and work with external stakeholders is just one of many stressors linked to the community college presidency, and a variable sometimes associated with presidential turnover (Tekniepe, 2014). The role of fundraising senior executive in any higher education institution has become a central focus of job responsibilities, with some college presidents reporting two-thirds of their job being related to fundraising. This time commitment has subsequent implications for college-wide operations, at times resulting in increased administrative costs to cover job responsibilities, and at other times, resulting in a more difficult role for the president.

The fundraising role of the college president has been studied in relation to four-year colleges and universities, but has received little attention in the two-year college sector as the responsibility has become more prominent. Therefore, the current study was designed to explore how current college presidents perceive their time commitment and responsibilities in external, private fundraising efforts.

Background of the Study

The American college presidency has changed greatly during the past several decades. Evolving from a strong curricular presence to an external relationship orientation. The result is that the position, in addition to a strategic policy mindset, requires a skill set and emotional intelligence that allows the individual to build partnerships, mediate political discussions, relate to faculty and the academic mission of the institution, and successfully raise money. This fundraising task has a strong historical root in the position, as the very first college presidents in North America were active fundraisers. Within the current context, however, the community college presidency is relatively new to the role.

Fundraising in the community college faces a number of unique challenges. Many students who enroll and complete a program of study view the experience as a functional step toward employment or a career, rather than an emotional developmental experience. The primarily non-residential experience, similarly, does not afford the community college the strength of connection often found with four-year institutions. The resulting difference in perspective that alumni have of their institution has historically promoted community college fundraising in the form of direct programmatic support, including sponsored training, and gifts-in-kind intended for training.

Community college fundraising has grown in importance, often as a result of limited financial growth from public sources, whether state allocations or local tax distribution (Miller & Holt, 2005). Many presidents have subsequently found that their infrastructure to raise money is underdeveloped and lacks the capability to raise significant amount of funds in short periods of time. The consequence has been an anecdotal reporting that presidents are spending significant amounts of their professional working time, in addition to their personal time and resources, to develop the networks and capacity to raise private funds for their institutions.

How funds are raised for an institution vary dramatically across institutional types and the infrastructure and resources they have to invest in resource development. Some institutions, for example, have donor prospect research programs that can identify and profile wealth and giving capacity, while others rely on part-time employees to use social media to identify best estimates of an individual’s capacity. Some institutions have multi-year, even decade long giving histories of individuals, and others do not. The variation, particularly in community colleges, is significant, and as Gyllin (2013) noted, a great deal of the preparation and implementation of fundraising is predicated on the emphasis given to it by college presidents.

Presidents face a multitude of challenges and constituents who they must serve (Miller, 2013). They must be internal to campus managers who lead by example, but must also assuage political interests, industry-based employers, accrediting agencies, and transfer destinations. Presidents, and chancellors must also serve as the public face of an institution, representing the college’s interests to not only these varied external stakeholders, but ultimately, to the students the college serves. The importance presidents give to development activities ultimately leads to the institution’s ability to raise funds (Garcia, 2009; Santovec, 2009)

With the increased pressure for fundraising activities and producing revenue for an institution, it has become important to understand how much time, attention, and energy presidents are investing in their development activities. Additionally, it is critical to understand the consequence of these activities and whether the time committed to development results in a higher level of resources raised for the institution (Falkner, 2017). Goodman (2015) stressed the need for understanding time committed to fundraising, and working with a sample of primarily minority community colleges, found a statistically significant correlation between time devoted to fundraising and fundraising success. Goodman also reported that on average, community college presidents spend half of their time (20 hours per week) raising funds for their institution, and in a qualitative study in the Midwest, Besikoff (2010) also found similar results of time commitment.

Research Methods

Data for the current study were obtained from surveying a stratified random sample of 100 community college presidents who were identified through internet searches. The colleges were geographically representative from the Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, Northwest, and Southwest (20 colleges from each area). The institutions all had an internet presence to the extent that senior college officials were identified with contact information.

The data collection instrument was a research-team developed survey that contained 12 questions. The questions all centered around the role of presidential leadership in fundraising, and the commitment that presidents placed in this activity. The question prompts were primarily derived from the literature, particularly the practitioner-oriented literature on the president’s role in fundraising in higher education. The instrument was pilot tested with a panel of four community college presidents and modified for clarity based on the panel’s feedback. The instrument was administered using an online survey protocol that included an initial email notification of the coming survey, the survey itself, and three reminders over a 16-day period.

A Cronbach alpha was computed on the survey instrument following its administration, and had a level of .0683, which was determined to be an acceptable level of reliability.

Findings

Following the first administration of the survey instrument, 28 college leaders completed the survey. After the first reminder was electronically sent to non-respondents, an additional 14 leaders completed the survey, 7 completed the survey after the second reminder, and 5 completed the survey after the third reminder. The total, usable number of responses was n=54 (54% response rate), which was deemed usable for both the exploratory nature of the study and the response rate for an online survey distribution.

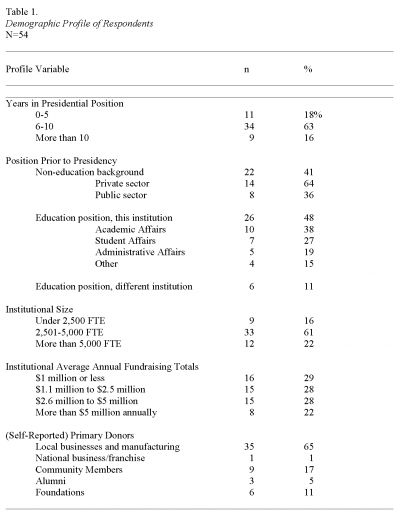

As shown in Table 1, over 80% of the presidents who responded to the survey had served in their role for under 10 years. Immediately prior to their assumption of the presidential position, over half held an administrative position at that same institution (59%), and just under half (41%) were employed outside of the education industry. Just over a tenth (11%) of the presidents held a position at a similar community college.

Over three-fourths of the colleges (83%) reported a full-time equivalent enrollment over 2,501 students. A fairly even distribution of fundraising totals was reported, with 29% of the institutions reporting raising $1 million or less per year, 28% raising between $1.1 and 2.5 million and between $2.6 and $5 million per year, and 5% raising more than $5 million annually. Presidents were also asked to indicate their primary donors, and over two-thirds (65%) reported that local business and manufacturing were the institution’s primary donors, 17% reported community members (individuals) as primary donors, and 11% reported private non-profit foundations as primary donors.

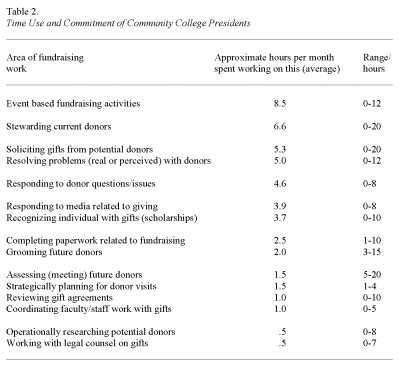

As shown in Table 2, community college presidents spent a total of 48.1 hours per month, or 30% of their working time, on fundraising activities. The greatest time commitment per month was the reporting of 8.5 hours of work each month on event based fundraising activities. These activities were anecdotally reported to be seasonal, as one president noted that he had five golf scrambles to raise money, and another commented that during basketball season he hosted a silent auction and similar events. The range of responses indicated that some presidents spent no hours each month on event based fundraising, while others spent as many as 12 hours per month.

The second most amount of time spent on fundraising was in the stewardship of donors, with an average of 6.6 hours per month and a range of no time spent on stewardship to 20 hours per month. The activities of soliciting gifts and resolving problems for donors both accounted for 5.3 and 5.0 hours per month, respectively. Responding to donor questions required 4.6 hours per month, meaning that on average, these presidents spent over one hour each week responding to things that donors are asking or requesting information on.

Alternatively, presidents reported spending 30 minutes per month, or less than 10 minutes per week, operationally researching potential donors or working with legal counsel on gifts. The range of responses, however, showed that some presidents spent more than 2 hours per week researching donors and nearly that amount of time (7 hours per month) working with legal counsel. This suggests a range of sophistication of the various fundraising operations represented in the sample institutions, with some requiring a more in-depth legal treatment of the binding nature and complexity of gifts.

Discussion

These findings provide an excellent point to begin the discussion about the changing roles and tasks of higher education leaders, and college presidents across all institutional types in particular. The 30% time commitment does not seem altogether extreme considering the importance of diversifying revenue streams, but when considering several individual tasks, the commitment to development becomes intrusive to other presidential tasks. For example, one respondent indicated that 20 hours were spent each month on stewarding current donors. That accounts for over 12% of the president’s work-life for a month, and that commitment must be traded for some other presidential activity.

An important next step for research will be to correlate time commitment and fundraising success in an attempt to help higher education leaders best understand how they can use their time and resources most efficiently. Other research could explore the effectiveness of different fundraising activities, in particular, examining the productivity and success of event-based fundraising as compared to focusing on individual major giving or planned giving. Such research might best be initiated in a case study format, and then expand to generalize and inform the community of presidents who are working so hard to raise funds for their institutions.

Overall, higher education administrators will only increasingly explore how they can build their institutions and work to accomplish their missions, and this will take a broader array of those who can provide revenue to make that happen. That means that fundraising programs and efforts will only increase in use and reliance, and that administrative preparation and in-service programs must address the needs and demands of the contemporary college president.

References

Besikoff, R. J. (2010). The role of the community college president in fundraising: A best practices study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California at Los Angeles.

Falkner, J. (2017). Presidential fundraising: A multiple case study of rural serving Oklahoma community colleges. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR.

Garcia, E. (2009). Texas community college fundraising: Strategies for meeting future financial needs. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas, Austin, TX.

Goddard, C. (2009). Presidential fundraising at independent colleges in the Midwest: A case study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Goodman, D. E. (2015). A study of fundraising practices of community college presidents at minority serving institutions. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD.

Gyllin, J. (2013). Donor profile of an urban southeastern community college: Profiles and giving patterns. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR.

Miller, M. T., & Holt, C. R. (2005). Sustaining local tax support for community colleges: Recommendations for college leaders. In S. Katsinas and J. C. Palmer (Eds.), Sustaining Financial Support for Community Colleges New Directions for Community Colleges Number 132 (pp. 67-76). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miller, M. W. (2013). The role of the community college president in fundraising: Perceptions of selected Michigan community college presidents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Santovec, M. L. (2009). Fundraising trickles down to community colleges. Women in Higher Education, 18, 8-9.

Tekniepe, R. J. (2014). Linking the occupational pressures of college presidents to presidential turnover. Community College Review, 42(2), 143-159.