Power of the Faculty: Consequences of No Confidence Votes for College Presidents

Daniel P. Nadler

Northern Kentucky University

Mei-Yan Lu

San Jose State University

Michael T. Miller

University of Arkansas

Correspondence related to this article should be addressed to Dr. Daniel P. Nadler, Vice President for Student Affairs, Northern Kentucky University, nadler@nku.edu

Abstract

The roles of college faculty members have changed, often in relation to increased specialization of their functions as either teachers or researchers. Similarly, the college presidency has changed, relying less on faculty interactions and increasing reliance and interaction on external stakeholders. The result is a less faculty-centric college presidency. The faculty, however, still have significant expectations for involvement with the college president and have the use of a no-confidence vote to express their opinions about the performance of the individual in the presidential position. Drawing upon a sample of faculty senate leaders, the current study found that few of these individuals know whether or not their campuses have formal guidelines for no-confidence votes, yet they do see them as effective tools for protesting the presidency and expressing their approval for the president’s performance.

The American college presidency has changed dramatically during the past 100 years. Although still very much the face of the institution, the roles, tasks, duties, and skills required for the presidency have changed to reflect how higher education has come to be viewed and the increased stakeholder involvement that drives the outcomes and actions of institutions. At the heart of the president’s role, however, remains a strong relationship with institutional faculty members. From the earliest institutionalization of higher education, these leaders who have evolved into “president” and “chancellor” titles have been required to maintain strong, positive working relationships with the faculty. The faculty, in turn, as a collective, have on occasion voiced their concern about the quality of the leader, offering votes of confidence, but more commonly, votes of no confidence.

Votes of no confidence are typically driven by faculty members who find some aspect of the senior leader’s behavior, management style, openness, and decision-making problematic. These votes are largely symbolic actions by groups of faculty members who are declaring, by conducting such a vote, that they believe passionately that a change is needed and that the formal system of institutional checks-and-balances does not or will not provide restitution in a way that they believe will accurately reflect their perceptions. The extent to which faculty members see these votes as binding or symbolic, however, is unknown.

Some institutions have formal guidelines for offering no-confidence votes, delineating who has the right to ‘vote,’ although most institutions do not have such a system defined in their faculty member guidelines or handbooks. At those institutions without formal guidelines for faculty expression in this manner, the faculty members who initiate and participate in the no-confidence vote process place themselves at potential risk of retribution, either by fellow faculty members or the administrators they are attempting to depose.

In addition to the fear of retribution, faculty members who decide to participate in a vote of no confidence must also consider the power of their collective voices. Dependent upon the board, with whom legal authority rests for the employment of the senior administrator (Smith, 2015), faculty members might resoundingly vote to remove or censure an administrator with immediate action by the board, or conversely, no action at all from the board. Therefore, it is critical that faculty members understand the scope and extent of their actions, and the purpose for conducting this study was to describe the current impact of no confidence votes on the college presidency.

Background of the Study

The relationship between faculty members and higher education leaders has historically varied dramatically. In some institutions, the president (or similarly titled official) is seen as the first-among-equals, assuming the leadership position to steward the institution for a period of time before returning to faculty duties. At other institutions, the presidential position is clearly delineated from faculty roles and is viewed as primarily an administrator or executive with responsibilities for institutional leadership. In this later model of presidential employment, individuals have moved into the college presidency without holding a faculty position at a greater rate than ever before (Braswell, 2006). This trend has been empowered by expectations that the college president must be concerned about a great deal more than instruction and student learning, and that this primary role is focused on fiscal management, donor and stakeholder relations, and legislative work.

The case for non-academic presidential leadership has grown greatly in the past two or three decades as the perception of what higher education is and is responsible for has changed. Hersh and Merrow (2005) places this change of focus in the 1980’s when perceptions of what higher education should result in changed in the public mindset. Hersh and Merrow argued that at some time early in that decade, higher education became seen as a private good focused on individuals enrolling in college as a form of job training rather than higher education enrollment as being a mechanism for the public good. This shift in thinking changed how students, and their parents and stakeholders, similarly viewed higher education, and instead of being a developmental experience, college enrollment became a pathway to better jobs and earnings. With such an economic orientation and outcome, the pathway for non-academic presidencies became more viable. No longer were presidents expected to be masters of student learning and teaching, but instead, to be a manager of a larger process focused on student personal gains.

As the shift in the orientation of what the college experience is for occurred, and presidents began entering their offices with a broader range of experience, ranging from the military to industry, their relationships with faculty members began to change. One of the fundamental changes that came from this differentiated career path was an appreciation for shared, collaborative governance, an historical hallmark of higher education. These leaders, and subsequently legislators and other policy makers, began to see efficiency and specified outcome measures like starting graduate salaries as the barometers of the public investment in higher education, and the inefficient, collaborative style that had governed higher education for hundreds of years became less critical to the modern institution. The difficulty for institutions was that the faculty did not change and neither did nor has their primary responsibilities. Rhoades (1998) referred to this change as the professoriate becoming a ‘managed profession’ with little power over the workplace.

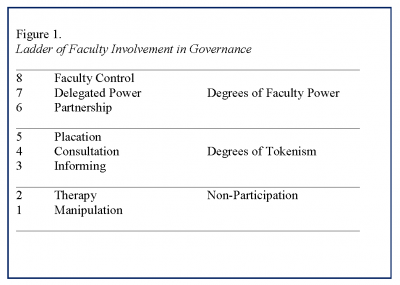

This change in faculty perception of personal empowerment has been seen in how faculty members view themselves, particularly in regard to their role in governing campus. Increasingly, faculty report feeling that shared governance has been eroded on their campuses, and well publicized events, such as faculty protesting the hiring of a non-academic as president at Iowa (Charis-Carlson, 2016), have reinforced their lack of ability to influence the academy. Some of this erosion might actually be related to how senior leaders and trustees view shared governance, including their view that such collaboration is really to placate faculty members ideas of involvement rather than entrusting them to make decisions. Miller (1999) described a progressive view of shared governance, where faculty power ranges from manipulation to complete control.

Additionally, statements continue to suggest that faculty are ‘in charge of the curriculum,’ but systems leaders have increasingly attempted to streamline curricula throughout higher education systems, and technology experts report needing to control access to information and how information flows to ‘end users.’ Both trends further restrict the role of the faculty, leaving them few outlets to formally challenge senior administrators and the decisions they make.

Faculty do engage in a range of activities to demonstrate their feelings about issues on campus, including protests, petition signing, and as is discussed in the current study, issuing votes to reflect a lack of trust, faith, or confidence in their institutions leaders. Despite a plethora of reports about no-confidence votes taking place at almost every type of institution, including private four-year institutions (Jaschik, 2017), community colleges (Flaherty, 2017), and public four-year universities (Tate, 2017), there is no indication that these votes result in any particular outcome. With an attitude of using such votes to publicly demonstrate feelings about a leader, these votes may not need to formally result in a specific action, but with the possibility of retribution, it is important to understand the consequences of faculty-led no-confidence votes.

Research Methods

Consistent with the purpose of the study, a two-part research design was utilized to describe faculty led no-confidence votes in higher education. The first part of the design utilized an ex post facto procedure, where the primary news outlet archives for higher education were searched for reports of no-confidence votes over a two-year period. The institutions that were identified as having a vote of this nature in regarding their leading campus official (president or chancellor title), were then researched to identify the outcome of the vote and ultimately, if there was a leadership change within a six-month period of time following the vote.

The second source of data was the distribution of a literature-based, three-part survey instrument that was sent to a sample of 100 faculty senate leaders (typically referred to as a chair or president of a faculty senate). The institutions were randomly selected using a table of random numbers from the membership of the Association of Public Land Grant Universities. The institutions were initially identified, and then searched to identify the faculty senate leader. A preliminary email was sent to these leaders indicating that the survey would be forthcoming, and approximately one week later, the electronic survey was sent to them. Two additional administrations of the survey were distributed.

The survey used in the study included three parts. The first section included five questions related to the prevalence and formality of no-confidence votes on their respective campuses. The second section included six items about the use and effectiveness of campus presidential leadership (meaning the senior campus official, referred to here as ‘president,’ but also inclusive of ‘chancellor’ on many campuses). The third section asked respondents about their perceptions of no-confidence votes on their campuses.

The survey instrument was constructed by the research team after considering relevant literature. The instrument was pilot tested with a panel of 10 faculty senate leaders at institutions not eligible for participation in the study. Wording changes were made based on panel feedback, and the instrument was re-distributed to the same members to check to see if the clarifications indeed addressed their concerns.

Data for the current study were collected in the Fall 2017 academic semester.

Findings

For the first part of the data collection, reports of faculty-led no-confidence votes were identified at 57 unique institutions. There were additional no-confidence votes reportedly conducted by staff or boards of trustees, but those were not included in this analyses. Of the 57 no-confidence votes, within six months of the actual vote, the campus leader was removed from office in 32 of those instances; 56% of the time a presidential change followed a faculty-led no-confidence vote. The reasons for departure varied dramatically, with the majority of those departures being non-voluntary on the part of the president (n=21; 66%), but they also included retirement, vacating the position for personal reasons (resignation), accepting a position at another institution, accepting a different position in the university or system, and in two cases, promotion within the university system.

For the survey data, of the 100 surveys that were distributed electronically, 53 were ultimately returned, and 49 of them were completed and used in the data analysis. Four surveys were only partially completed and subsequently not used in the analysis.

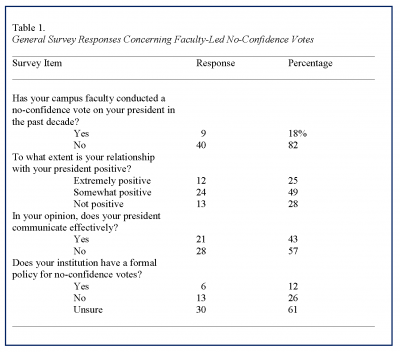

Less than 10 of the respondents (n=9; 18%) reported having conducted a faculty-led no-confidence vote in the past decade (see Table 1), indicating that such occurrences were rare. Consistent with the rarely-used no-confidence vote, 61% of the respondents were not even aware of whether or not their campus had a formal policy on no-confidence votes. Another possible reason for the lack of no-confidence votes was that nearly two-thirds of the respondents were somewhat to extremely positive about their president (74%). Despite this, less than half (43%) perceived their president to communicate effectively.

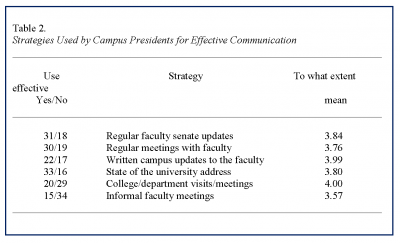

As shown in Table 2, responding faculty senate leaders were asked about the communication style and its effectiveness of college presidents. The most common methods that presidents used to communicate with their faculty were delivering a state of the university address (n=33), updates at faculty senate meetings (n=31), and regular meetings with faculty members (n=30). The perceived most effective methods for presidential communication with faculty were college and/or departmental faculty meetings and visits (mean 4.0) and written campus updates delivered to the faculty (mean 3.99). The most frequently used presidential communication method, delivering a state of the university address, was also perceived to be the least effective way of communicating with faculty (mean 3.59).

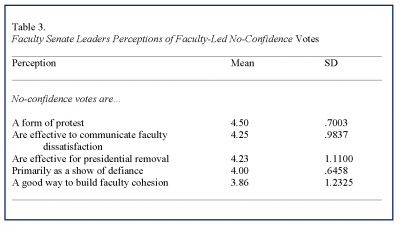

In terms of perceptions (as shown in Table 3) of the role of faculty-led no-confidence votes, faculty senate leaders agreed most strongly that no confidence votes are a show of protest (mean 4.50), are an effective communication of faculty dissatisfaction (mean 4.2), and that they are effective at removing a president from office (mean 4.23).

Discussion

No-confidence votes appeared to be popular mechanisms for faculty members to express their displeasure in institutional leadership. In addition to being an opportunity for faculty to band together, these votes are also headline-grabbing, appearing in popular on-line and print-based popular and trade publications. Despite the opportunistic use of such votes, in over half of the instances where there was a no-confidence vote, there was presidential leadership change. The current study did not attempt to look at the causation of change, but the instigation of the vote most likely was a reflection of a serious problem in leadership.

As higher education changes, the role of the faculty similarly change. No longer in control of the campus, or even its internal operations, faculty members are in a position to provide a check-and-balance of administrative leadership. Through activities such as a no-confidence vote, they at the very least can indicate and express their belief about what is presumably best for the institution to fulfill its mission of teaching, research, and service.

Faculty members must be cautious, though, in their use of public displays of support or non-support of popular issues or administrative leaders. Their role is to work for the best interest of the institution, and not necessarily what might be considered a political agenda. Similarly, faculty, trustees, administrators, and public policy makers must become more aware of their surroundings and what it will take to effectively lead higher education throughout the next century. This leadership will most likely entail a strong sense of business-like management, yet with a mission of supporting the public good, a vision beyond financial gain is critical for these institutions.

References

American Council on Education. (2017). American college president study 2017. Retrieved online www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/American-College-President-Study

Braswell, K. (2006). A grounded theory describing the process of executive succession at Middle State University. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

Charis-Carlson, J. (2016, June 18). University of Iowa sanctioned by national professor group. Des Moines Register. Retrieved online at www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/education/2016/06/18/national-professor-group-sanctions-university-iowa/86085620

Flaherty, C. (2017, October 2). No-confidence vote at Southern West Virginia. Insidehighered.com. Retrieved from www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2017/10/02/no-confidence-vote-southern-west-virginia

Hersh, R. H., & Merrow, J. (Eds.). (2005). Declining by degrees. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press Griffin.

Jaschik, S. (2017, October 20). Vote of no confidence at Assumption. Insidehighered.com. Retrieved online at www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2017/10/20/vote-no-confidence-assumption

Miller, M. T. (1999). Conceptualizing faculty involvement in governance. In M. T. Miller (ed.), Responsive academic decision making, involving faculty in higher education governance (pp. 3-28). Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

Rhoades, G. (1998). Managed professionals, unionized faculty and restructuring academic labor. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Smith, R. V. (2015). Where you stand is where you sit. In. R. J. Sternberg, E. Davis, A. C. Mason, R. V. Smith, J. S.Vitter, and M. Wheatly (eds.), Academic Leadership in Higher Education (pp. 135-142). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Sternberg, R. J., Davis, E., Mason, A. C., Smith, R. V., Vitter, J. S., & Wheatley, M. (Eds.). (2015). Academic leadership in higher education. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Tate, E. (2017, May 8). William Patterson faculty votes no confidence in president. Insidehighered.com. Retrieved from www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2017/05/08/william-paterson-faculty-votes-no-confidence-president