Charles P. Ruch

Boise State University

Kenneth M. Coll

University of Nevada-Reno

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Charles P. Ruch, President Emeritus, Boise State University, chuckruch38@gmail.com

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every institution of higher education differently. It is recognized that a return to pre-pandemic institutional life is no longer possible. Presidential leadership is being required to reposition the institution to face this new era. One of the most vexing results of the pandemic is the emergence of student, faculty and staff mental health and wellness as a priority issue. Upon examination, the campus mental health crisis encompasses most aspects of campus life. The purpose of this review is threefold: 1) to illuminate the impact of campus mental health and wellness issues 2) to outline institutional challenges and options, and 3) to propose a set of strategic actions for presidential leadership to respond to the campus mental health crisis.

With the COVID-19 pandemic slowly receding, higher education institutions are examining its impact and developing responses deemed appropriate for the new environment. Stakeholders across the institution, led by the president and Board, are recognizing that a complete return to post past pandemic life is not a useful or desirable path. Two plus years of suspended or redesigned functions, periods of isolation and new modes of communication, and fiscal challenges have taken a toll. Their impact cannot be discounted. New priorities have arisen as in changes installed to handle pandemic life offer new challenges going forward. As presidents confront this new institutional life, these leadership challenges and options require revised priorities and invite new strategies.

Campus mental health and wellness has become a seminal challenge emerging from the pandemic. Once a matter delegated to student affairs and HR, campus mental health is now a cabinet level matter, demanding presidential attention and leadership. The purpose of this review is to illuminate the impact of campus mental health issues, outline institutional options and challenges, and propose a set of strategic actions for presidential leadership to respond to the campus mental health crisis.

Campus Mental Health Issues

The roots of the post pandemic campus mental health crisis are long standing. Student mental health has been found to be related to academic success, completion, and wellness across all sectors of higher education. For example, Eisenberg, et al. (2009) found students reporting depression, anxiety, or eating disorders had lower GPA and higher probability of dropping out. Wyatt, et al. (2017) reported differences in academic performance and mental health between first year and upper-class students. Trenz et al. (2015) found similar differences between traditional and non-traditional student groups.

Recognizing the impact of mental health on student learning and engagement was the conclusion of a yearlong analysis conducted by the American Council on Education, the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, and the American Psychology Association. Increased support of mental health services is recommended to ensure that each institution provides students with needed help (Douce & Keeling, 2014). Even prior to the pandemic (June 2019) the National Academics of Science, Engineering and Medicine launched an 18-month study to examine campus response to the growing number of student mental health issues. The report (National Academies of Science and Engineering, 2021) called for mental health to become an immediate institutional wide priority, with enhanced attention and programming to respond to student mental health issues, now even more pronounced by the pandemic.

Meanwhile, institutional response to campus mental health matters has been mixed, ranging from minimal and uncoordinated to several notable campus-wide comprehensive programs (see Chessman, et al., 2020, December 10). However, the former is the typical response pattern.

The most frequent locations for mental health programs and leadership are student affairs and HR. The most common resources for students are centered in the counseling center and peer support, especially in residential housing. Most staff/faculty mental health services are facilitated by HR and often utilized state employee assistance programs (EARs) and/or community agencies. In many colleges and universities, the available mental health workforce was insufficient to meet needs. Most services are individually oriented and involved face to face interventions. Beyond an individual crisis that garner campus/community wide attention, campus mental health matters have rarely been a matter for sustained presidential, cabinet and/or Board attention.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically challenged institutional response and thrust the matter to the president’s office.

Impact on Presidents and Cabinet Level Administrators

Two national surveys conducted during the two years of the pandemic highlight presidential awareness and concern with campus mental health issues.

In fall 2020 and again in spring 2021 the American Council on Education (ACE) and TIAA surveyed a national sample of college presidents. In the earlier survey 68% responded that student mental health was their most pressing problem. The next semester the issue was identified by 72% of the presidents as the top issue. Mental health of faculty & staff was second; 60% and 58% respectively. Differences across institutional type were reported with presidents at public four-year institutions and presidents at private four-year institutions indicated ‘mental health of students ‘the highest pressing issue (82 % and 73% respectively). Presidents at two-year institutions reported ‘enrollment numbers for spring 2021’ being their most pressing problem (66%). (Taylor, et al., 2021a, Taylor, et al., 2021b).

The Inside Higher Ed and Hanover Research 2021 and 2022 annual survey of College and University Presidents found leadership awareness and concern for the campus mental health crisis. The 2021 survey reported that 96% of the respondents were “very concerned or somewhat concerned” about student mental health. Presidents expressed specific apprehensions that mental health issues disproportionately impacted students from disadvantaged background. Ninety-four (94%) percent of the respondents expressed similar concerns for the mental health of institutional employees (Jaschik & Lederman, 2021).

The 2022 Survey reported similar results. Jaschik & Lederman (2022c) concluded “almost all presidents report they are “somewhat” or “very aware” of the state of mental health as it relates to staff, undergraduate students, and faculty (p 5)”.

Surveys of other cabinet members also reveal awareness of mental health issues in their area of responsibility. The 2022 INSIDE HIGHER ED Survey of College and University Chief Academic Officer found two thirds (65%) of the respondents reporting they are “very aware of faculty mental health, followed by undergraduate students, staff, and graduate students’. Provosts at private institutions also reported a greater awareness of graduate student mental health issues that those from public institutions (82% to 49% respectively (Jaschik & Lederman, 2022a, p 10).

In a similar survey, 2022 INSIDE HIGHER ED Survey of College and University Business Officers, reported that many institutions (65%) increased investment in mental health services. Furthermore, 59% of the business officer respondents indicated these increases would continue into the next academic year (Jaschik & Lederman, 2022b, p.17-18).

During the pandemic, student affairs officers were surveyed (2020 INSIDE HIGHER ED Survey of College and University Student Affairs Officers). Almost all (94%) student affairs officers reported spending a significant amount of their time on matters involving student well-being (91%) and mental health (94%) including addressing student hunger and homelessness. Yet only 35% of the student affairs officers evaluate the state of student mental health on their campus positively (Jaschik & Lederman, 2020).

Impact on Students

During the pandemic incidents of student mental health issues increased (HealthyMinds Network & American College Health Association, 2020, September). Lederer, et. al. (2021) observed that “College students now face increasing housing and food insecurity, financial hardships, a lack of social connectedness and sense of belonging, uncertainty about the future, and access issues that impede their academic performance and well-being (p 14)”. The co-concurrence of food and housing insecurities with mental health problems was found to be of significance when viewing the mental health crisis among community college students (Brotron, et al., 2022).

A survey of 27,118 students from eight large research universities located across different regions of the US examined a plethora of individual measures wellness and mental health. (Soria & Horgos (2021) found increased prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

All four studies found historically underserved and marginalized student groups with increased rates of mental health disorders and concerns coupled with health and safety issues. The few campuses with comprehensive services reported lower rates of mental health concerns.

The decline in student enrollment trend over the previous decade accelerated during the pandemic. All sectors experienced decline. Student seeking associate degrees and students seeking part-time enrollment reported the greatest decline. This trend is reflected most dramatically with community college enrollments down over 9% over the two-year pandemic (American Council on Education, July 2022). Evidence is emerging that this trend is continuing. The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center report a 4.1% decline in total enrollment for spring 2022 (Moody, 2022, May 26).

Mental health concerns are one of the most cited reasons students identified as influencing withdrawal during the pandemic. Gallup-Lumina surveyed of over 11,000 adults, both college students, dropouts, and those considering enrolling. Stress issues were the most reported reason for contemplating or dropping out (Spitalinik, 2022, April 20). The Sallie Mae and Ipsos survey examined differences between completers and non-completers. Fourteen percent (14%) of the student surveyed who dropped out cited mental health challenges as the primary reason. (ACE blog, 2022, July 15).

A survey by TimelyMD of nearly 1200 college student respondents who planned on returning to school in fall 2022 presented findings indicate that the mental health crisis continues. However, the data suggests the sources of student stress may be changing. Concerns about the pandemic, the major reason of student stress in the previous survey, declined. Mass shootings (41%), inflation (40%), finances (44%), and academics (38%) were among the reasons students linked with stress and mental health issues (Edelman, 2022, August 12).

Mental health issues and services are emerging as a factor in the student recruitment process. Caron suggests that students and parents should “make a mental health checklist’ when considering a college to attend (2022, July 11).

Impact on Faculty and Staff

Mental health problems are now recognized as of concern across faculty and staff. For example, Meeks et al. (2021) in a survey of 448 students and faculty/staff from a Midwestern University found nearly one third of the campus community experienced symptoms consistent with severe/very severe depression (28.3% faculty/staff), anxiety (38.6% faculty/staff) or stress (31.1% faculty/staff).

A survey of l29 employees at a private institution in the Midwest reported a mixed response to physical and mental health during the early part of the pandemic. A third were challenged with concerns about physical activity, eating, sleep habits and weight management. More than half reported greater stress, anxiety and mood change and less healthy eating habits. No significant difference was found between gender or employment type. (Peacock, 2021).

Melnyk, et.al. (2021) surveyed 2,138 faculty and 2,226 staff during the pandemic at a larger mid-west public land grant university. Eighteen (18%) to 27% of faculty and 25%-31% of staff met the DSM cut-off for clinical anxiety. The rates for depression were 4.4%-8.3% for faculty and 9.7%-10.0% for staff.

The pandemic created an environment that faculty report significant increase in symptoms that highly correlate with burnout. The Course Hero (2020) study of more than 570 full and parttime faculty at two-and four-year colleges and university found more than three of four (74%) of the respondents reporting significant stress caused by challenges using new modes of teaching. About two thirds felt that the challenges of meeting the emotional and mental health of students caused significant stress. Moreover, while stress was high at the beginning of pandemic, faculty report peek stress increasing as the pandemic continued. Overwhelmingly, faculty believe their job has become more difficult because of COVID.

Impact on Faculty and Staff Recruitment and Retention

Just as students facing the impact of the pandemic on their academic life elected to either drop-out or stop-out, faculty and staff report level of dissatisfaction with their current job to consider a change. Retention of college and university faculty and staff is on the decline. The Course Hero (2020) survey found 40% of the responding faculty considering a job move. Salary was the most cited reason, followed by work environment issues (e.g., load, flexibility, support services, etc.).

The 2022 College and University Professional Association-Human Resources (CUPA-HR) surveyed 32,815 higher education employees at 949 institutions across 15 different departments/functional areas. More than half (57%) of the workforce reported considering a move over the next 12 months. Increase in salary was the number one reason for their move. However, nearly three fourth reported a frustration with remote work options and were seeking a hybrid work schedule (Bichsel et.al., 2022). The 2022 State of Work Survey of over 550 higher ed employees by Grant Thornton found similar findings. While l7% of the respondents were actively looking for a new job, 49% reported they would switch if a new opportunity presented itself (Spitalniak, 2022). Winfield & Paris (2022) found similar factors contributing to burnout and retention across 1411 members of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admission Officers (AACRAO).

The National Association of Student Affairs Administrators (NASPA) report, The Compass Report: Charting the Future of Student Affairs (2022) chronicled the responses from l8 focus groups with 97 student affairs administrators, student affairs faculty and graduate students across all position levels. The study was also informed with results of a survey of a national sample of 1,005 student affairs administrators across all levels and institutional types. A significant finding was that early and mid-career student affairs professionals are leaving the field for other pursuits. Compensation and work environment issues, influenced by the pandemic, were the most common reasons cited for leaving.

Paralleling faculty and staff retention and attrition is growing concern for filling vacancies with qualified applicants. A Chronicle of Higher Education and Huron Consulting Group study found “shallow and weak” applicant pools. Over three-fourths (78%) of the respondents reported fewer applications for vacancies in the last year, and 82% noted that they had received ‘fewer applications from qualified candidates’ (Zahneis, 2022).

A continuing impact of the pandemic is the restructuring of the academic workforce. Marketplace compensation and increased workplace flexibility offered by competing employers, including other colleges or universities, give staff and faculty additional opportunities. Plans for new workforce structure and actions are emerging (Brantley & Shonmaker, 2021; Segio, 2021).

Institutional Options and Challenges

Prior to the pandemic most college and universities employed several programmatic options to address campus mental health, wellness, and workplace issues. Options utilized are a function of institutional characteristics such as mission, history, location, type, size, resources, and student demographics and characteristics. Clearly, ‘one size fits all’ set of services and programs does not describe the landscape.

The two years of COVID 19 impacted these services and programs. Prior to the pandemic these programs and services were the primary responsibility of student affairs and HR. In the new environment, they are now matters which demand institution wide emphasis and need presidential attention and leadership. To provide a context for a discussion of alternatives for presidential action, it is instructive to briefly review these services and programs with attention the impact of two years of pandemic on their operations.

Student Focused Services and Programs

Mental Health issues are individual in nature and characterized by recognized clinical diagnosis. Several service strategies are found in colleges or universities to assist students presenting these problems.

Counseling Centers and Services

Institutional counseling centers have a long tradition of being at the heart of the any program to assist students experiencing mental health problems. Studies and reports have documented their impact and import (for example Douce & Keeling, 2014; Francis & Horn, 2017).

Across the higher education landscape, the characteristics of counseling centers present a mosaic of size, staffing, theoretical/philosophical orientation and services. Counseling Centers can be distinguished by their underlying philosophy and organizational structure. Mitchell et al. (2019) reviewed the several models across the membership of the Association for University and College Center Directors (AUCCCD). Two approaches dominated their analysis: the medical model or the student development model. On some campuses units representing both models are present; or the two are combined into one unit.

The comprehensive counseling center model (CCC) is articulated by Brunner et al. (2017). These centers provide a full range of services including direct services, extensive outreach, consultation services, and research and training. They are guided by a student development philosophy and a total campus involvement. Many of these centers use a stepped care model for matching student needs with a range of services. Smaller centers are less inclined to use this model (Vespia, 2007). While most community college centers do not utilize this model, Dykes-Anderson (2013) argue this model is most consistent with the community college mission.

The alternative model is the Integrated Care model where the single function of the unit is providing individual counseling or therapy. The model often employs a team-based approach where physical and mental health services are provided concurrently often in the same setting. There is a higher frequency of smaller centers (Vespia, 2007; Wilcock & Stiles, 2017) and at community colleges where counseling center has ties with community medical clinics (Katz & Davison, 2014) who are grounded in this approach.

Prior to the pandemic many counseling centers reported being understaffed as the mental health concerns of students increased (Lipson et al., 2019). This trend has exacerbated over the past several years. Institutions with underrepresented student populations have reported a continuing challenge to meet expanded demand (Abrams, 2020).

During the pandemic, institutions responded to the needs for additional mental health professionals and staff. Three in ten counseling center directors reported an increase in staff positions, while less than fifteen percent reported loss of positions (31.6% versus 13.8% respectively). While the need is high, conversely over the pandemic, 58.6% of center directors reported a decline in for counseling services. Due to access, they reported that, on average, 6.4% fewer clients were served in 2020 than in 2019 (AUCCCD Annual Survey: 2020, 2021). The federal COVID funding was utilized by institutions to support additional mental health staff and accessibility. The continuation of these funds is problematic suggesting the need for a planned institutional response. Prioritizing additional mental health staff as the best strategy to respond to student mental health needs has been questioned (Frank, 2022).

Teletherapy, Telemental Health, and Telesupport

The most visible impact of the pandemic is the dramatic increase in use of technology across all dimensions of institutional life. Almost overnight, counseling centers and staff moved to a virtual delivery model. The impact of this shift is reflected in the finding from the 2020 AUCCCD Annual Report which notes, “In the 8 ½ months prior to March 15, 2020, counseling centers averaged l7.l video sessions but averaged ll64.8 sessions from March l6, 2020 to June 30, 2020. This is a 6811% increase (AUCCCD Annual Survey: 2020, p.4)”.

In general, students responded positively to this shift in delivery mode. They view tele-mental health as convenient, accessible, easy to use and helpful. Shortcomings were reported to be “lack of connection to the provider” or “lack of customization (Hadler et al., 2021)”. Spitalniak (2022) provided annotated responses from students in support of telemental health, especially during semester breaks.

A recent survey of chief online officers reported the largest resource increases during the pandemic was for online mental health services. None of the 283 respondents noted a reduction in resources in this avenue of online student support during that period (Koenig, 2022).

The continuance of telemental health beyond the pandemic is yet to be determined. Many of the issues to be considered are outlined in the Higher Education Mental Health Alliance guide; College Counseling from a Distance (2019). Shwitzer and Sixbey (2022) reviewed the evolution of the use of technology in student affairs while Rosenbaum & Oakley (2020) reflect on the changes to college life. Hadler et al., (2021) describe the new world of higher education characterized by an increased use of technology.

Recent studies report on developing trends in online education (Kelly, 2022) where still to be defined ‘hybrid’ is the model of choice. The recent Chronicle of Higher Education & P3*EDU 2202 Public-Private Partnership Survey of presidents found the highest area of interest (44%) was partnering with private companies to provide telehealth/mental services (2022).

The creation of the national Suicide Prevention/Crisis hotline, 988, is a service that will need to be integrated into campus mental health planning.

Peer Counseling

Many campuses use students as peer counselors. D’Andrea (2008) reviewed the evolution of peer counseling training in colleges and universities. This study focused on five years of data from several institutions. Training increased program and services across l7 health and wellness topics. Studies by Wawrzynski & Lemon (2021) and Haseltime (2021) outlined peer counseling efficacy with student mental health problems.

The Mary Christie Institute/ Born This Way Foundation (2022) conducted a national survey of 2,221 students regarding their experience with peer counselors. Among their findings were:

- One in five college students already use peer counseling (20%); Of those who don’t use it, 62% are interested in doing so. Interest in peer counseling among students is higher since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

- Satisfaction with peer counseling is high, with nearly 60% of students who used the service calling it helpful. 82% of students who have peer counseling at their school say it was ‘able to serve students of various backgrounds and identities.

- Peer counseling training is common (93%) but not universal. Further, l6% of peer counselors say they are unaware of an emergency protocol if they become worried for a student’s safety (p 4)

Faculty Support

Faculty, while not mental health professionals, have an important role in addressing student mental health problems. They interact with students in classroom settings, provide advising, and engage students in informal conversations. Consequently, they can aid in the identification of students in distress and assist in their seeking professional help.

A study by Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), Mary Christie Foundation (MCF) and the Health Minds Network (HMN) surveyed l685 faculty members at 12 colleges and universities in January 2021 regarding their experiences and perspectives with student mental health. About 80% of the responding faculty reported having had a one-to-one phone, video or e-mail conversations with students over the preceding twelve months regarding a mental health issue. Respondents felt they had a responsibility to help students address mental health matters, a contrast to the often-held assumption that ‘it isn’t my job.’ The need for training was expressed by 73% of the faculty responding with 61% believing it should be required (Mary Christie Institute, 2021, p.4).

Needed faculty preparation to be effective in providing student support is documented in the work of Wiest & Treacy (2019) and Trela (2008). Coleman (2022) presents a set of ‘best practices’ for faculty who are interested in supporting students with mental health problems.

Faculty/Staff Focused Services and Programs

While faculty and staff experienced mental health problems prior to the pandemic, its impact was felt across the workforce. Reports of increased cases of burn out, stress, anxiety, depression during the pandemic illustrate that these problems continue (Melnyk et al., 2021). There is some information and analysis regarding available institutional resources to assist the campus workforce including the work of Riba et al. (2022).

A scan of the literature and institutional documents result in three options of institutional support: counseling centers, employee assistance programs EAPs), or referral to community agencies.

Some institutions permit faculty or staff to utilize the services of the counseling center. This is most frequently at institutions where counseling and health services are integrated.

Many public college and universities either host or have access to employee assistance programs. In an earlier study, Grosch et al. (2009) surveyed ll5 programs across higher education. These EAPs were similar in design, services offered and availability to those in private industry. Faculty use was proportionally less than for staff or administrators. A review of the several dimensions of EAP’s in higher education is found in Maiden and Philips, eds., (2008). Confounding issues include the scope (counseling versus comprehensive set of health/welfare services), location (on campus versus community), mode of referral (self or other), and relationship to faculty/staff fringe benefits (health care plan, state sponsored program, etc.).

A typical option is to offer 3-5 individual mental health sessions for staff/faculty with direct referral to community centers or clinics.

Campus Wide Programs

One of the significant characteristics of a college or university is its sense of community. Institutional culture is built around face to face and small group interactions, building a sense of belonging, support, and identity. Institutions often conduct an intentional strategy to enhance campus culture. Campus wide programs often focus on overall wellbeing, including health and mental health. The total campus disruption forced by the pandemic has resulted in a variety of studies and reports focusing on both the impact on prior program design and needed readjustment.

A review of the existing literature of current evidence-based practices promoting a campus culture of wellness was conducted by Amaya et al., (2019). Drawing on the literature and case studies from nine universities from the National Consortium for Building Health Academic Communities, fifteen best practices strategies were developed. They reinforced the eight dimensions of wellness articulated by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, i.e., physical, intellectual, environmental, financial, occupational, social, emotional, and spiritual (SAMHSA, 2016). A common program delivery was a series of workshops across the dimensions, available across campus.

The ACHA’s Health Campus program sponsored an initiative for campuses to improve the health (including mental health) of students, faculty and staff using national objectives. Many campuses found the model inconsistent with their mission and student body characteristics. The program was found to require a resource level beyond what institutions were will/able to invest. This comprehensive, the ‘one size fits all approach’ limited scaling up across higher education. In 2020, ACHA revised its Health Campus Framework which now focuses on a broad set of elements and facilitate an individual campus orientation to design, implementation and evaluation. (American College Health Association, 2022).

A third study of campus wide well-being programs was conducted by the American College Health Foundation and Aetna Student Health. Travia et al. (2022) reported findings from a study of ten institutions of higher education across three major categories, student serving programs, employee service programs, and hybrid programs. Data from key stakeholders and focus groups resulted in several trends. Of significance were movement away from more traditional health education practices to a more systematic, environmental approach and a general utilization of the eight dimensions of the wellness model. A range of involvement with comprehensive programs was found with variance attributed to institutional mission, philosophy, and resource based. Many institutions are designing programs to address health disparities among underrepresented or marginalized populations (Travia et al., 2022, p. 1).

Reports from the Association of Governing Boards (AGB) articulate the need to redesign mental health services suggesting that this is an issue that needs to find its way into governing board discussions (Shiemann, 2021; West, 2022).

Other studies calling for additional support for mental health services and comprehensive redesign come from both within and beyond the academy. For example, the Chronicle of Higher Education/Huron Consulting Group survey of college presidents and chief student affairs officers, (Rudley, 2018), the Rand Corporation study (Sontag-Padilla, 2020), or a survey conducted by Fortune (Leonhardt, 2022). California State University, Long Beach announced a comprehensive redesign of its mental health initiatives using this as major institutional characteristic and emphasis (Carrasco, 2022).

Workplace Initiatives

The impact of the pandemic on the global workplace is just being realized. Kniffin et al. (2021) present an analysis of the pandemic on important workplace practices and changes for workers. Their analysis highlights these changes along individual and organizational variables. In short, the workplace has changed with little or no possibility of return to pre-pandemic characteristics. Every organization, including colleges and universities, will need to readjust practices to meet this new era.

The immediate impact on higher education workforce is reflected in the CUPA-HR study. The three top reasons of faculty/staff dissatisfaction with their current assignment were pay, current institutional policies around remote and flex work, and ever-increasing workload. Once viewed as a desired work setting, high education must now compete with both other institutions and the private sector who offer more responsive policies and procedures (Greenfield, 2022; Moody, 2022; Spitainiak, 2022; Yakoboski & Fuesting, 2022).

Based on their work at CUPA-HR, Brantley & Shomaker, (2021) outline possible practices that higher education institutions should consider in response to the changed workforce and workplace. Examined are needed policies and procedures for remote work, training and support for retooling skills, revising employment procedures and policies, enhanced well-being and Employee Assistance programs, and increased support for childcare facilities. Waters (2022) review the history of telework and provide a model for institutions to guide redesign of the work setting telecommunication.

In short, it is argued that it will take new, focused, and intentional strategies to make the institution the ‘employer of choice’ for current and future staff.

Summary and Implications for Presidents

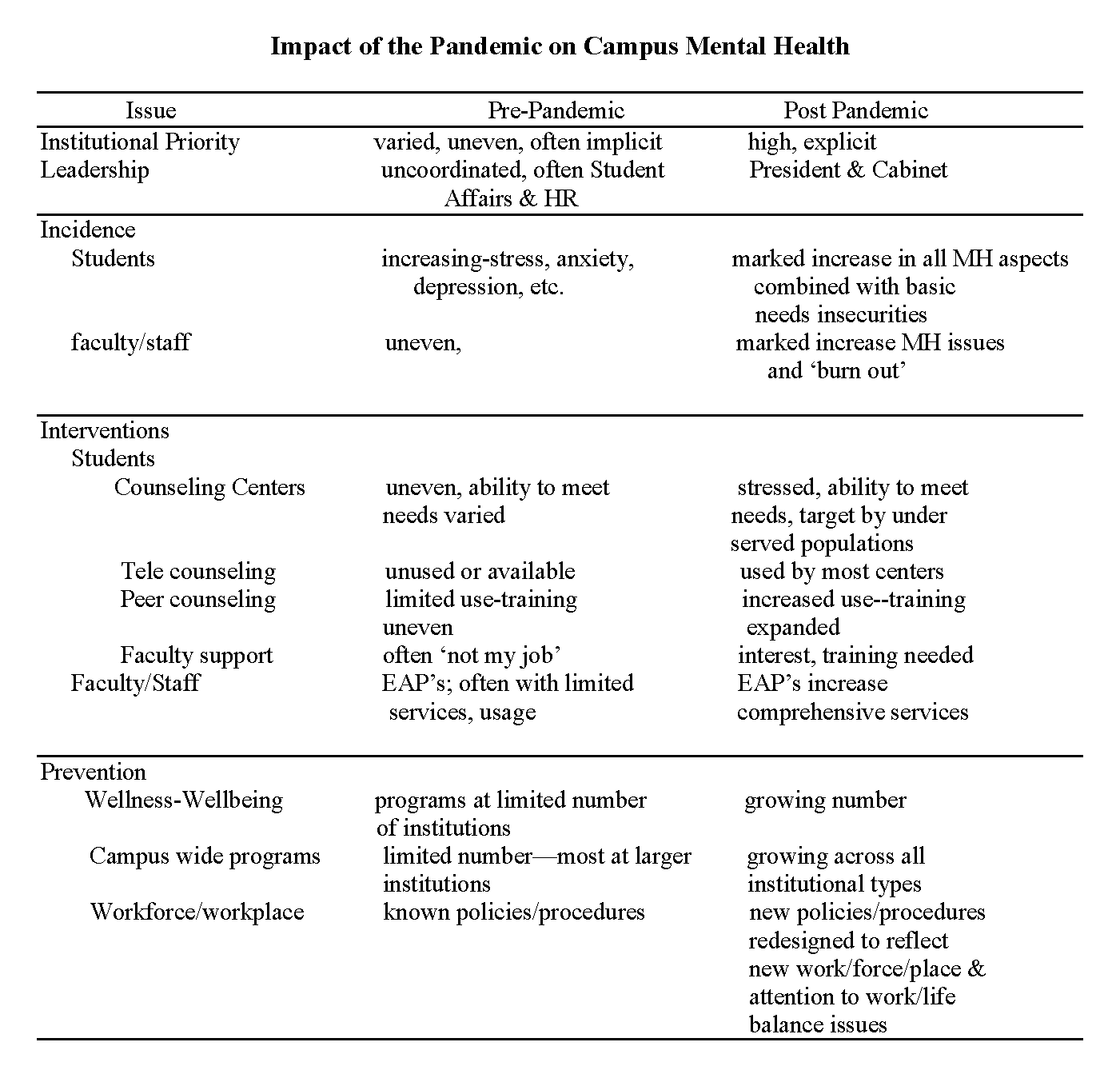

The pandemic has affected all dimensions of a college or university. There is little evidence that the institution will return to pre- pandemic conditions. These changes are summarized in the following chart.

When viewed in totality, a comprehensive, coordinated, camps wide strategy is called for. Only the president can cause such a ‘plan forward’ to be designed, resourced, implemented and evaluated. Responding to the mental health crisis, illuminated through pandemic experiences, will need become a major fabric in the mosaic of the individual campus culture and operation. Presidential leadership is central to this effort and may be the key to some institution’s survival in the post pandemic era.

Presidential Response — Strategy and Implementation

Every college and university experiences the pandemic differently. All aspects of collegiate life were affected. Repositioning the institution to meet the characteristics of the post pandemic era is a new challenge requiring presidential vision and leadership. Responding to the mental health across campus is fundamental to build the future of the institution. Leadership from the president is critical to both the strengthening a response to the crisis and central to the post pandemic repositioned college or university.

The crafting and implementation of a strategy to respond to the mental health needs of the campus can no longer be a marginal function with fragmented delivery and bifurcated leadership. Institutional mission, history, location, student composition and resource base will texture the future of mental health responses, successful institutions will need specific presidential involvement and explicit institutional actions. The following are elements for a suggested presidential strategy to respond to this campus challenge.

Establish Responding to the Campus Mental Health Crisis as an Institution Wide Priority

Each president will need to consider current campus mechanism for increasing focus and visibility on campus mental health, wellness, and work setting as priority items. The president needs to articulate this highest priority visibility and consistently. The campus mental health crisis should be a matter of frequent discussion with the governing board, and a priority focus of the president’s cabinet.

The use of a campus wide task forces was a successful pre pandemic strategy directed at campus mental health. The American Council on Education (ACE) examined the work of such committees across l0 universities and colleges. Their report illuminates many of the critical considerations and strategies that were reported associated with success. In all cases, the task force was appointed by and report directly to the president/provost (Chessman et al., 2021). The importance of this issue to the future of the institution suggests that the ‘taskforce’ approach might need be augmented and expanded.

Conduct an Immediate ‘Audit’ of the Campus Mental Health Crisis

Immediately the assembling of all currently available data regarding both the extent of mental health problems across students, faculty, and staff and availability of services is a necessary starting point. The president should cause an ‘audit’ of the campus mental health crisis.

Give the frequent institution practice of unit maintaining their own data base, the president will need to assure that data from all sources is available for the ‘audit.’

How such data is collected, organized, and analyzed will be institution specific. The involvement of stakeholders in the design of the ‘audit’ will contribute to understanding and acceptance of the findings. Care should be taken to avoid ‘over studying’ the problem. A small budget, temporary support staff, a clear directive of anticipated work product, and an aggressive timeline are tangible ways presidents can illuminate the critical importance of the work.

Nine models (frameworks) useful or organizing an audit of campus mental health issues and seven that focus on service providers are presented in the ACE Mental Health Task Force (2020). The Health Minds Network/Active Minds/Jed Foundation published a toolkit of mental health data and statistics which could serve as a starting reference for the campus audit.

The ’audit’ may be called upon to make recommendations. Additionally, it might identify needed data sets, currently unavailable, and a plan to include them in future ‘audits.’ Most importantly, a schedule for future ‘audits’ should be announced. A ‘one and done’ approach will suggest that this priority is more ’talk’ and ‘walk.’

Develop a Campus Wide Plan to Address the Mental Health Crisis.

The repositing of each college and university in the post pandemic environment is a topic of growing interest (for example, Felix et al., 2020; Malanson, 2022). Mental Health planning can serve as a critical element in the over-all repositioning of the institution.

The Jed Foundation has collaborated with several other organizations and agencies to produce a series of resources to guide comprehensive campus mental health planning including the Guide to Campus Mental Health Action Planning (The Jed Foundation/EDC, 2011) and an updated Jed’s Comprehensive Approach to Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention for Colleges and Universities (2021). These models can serve as a basis for developing a campus wide plan.

Traditional strategic planning models are being augmented by planning models that focus on creating a future view(s) of the institution, defining its future characteristics and then planning ‘backward’ to create a set of priorities, events, and interventions for a ‘path forward.’ Scenario planning models (for example, Amer, 2013; DeloitteU.S, 2020; Hanover, 2021; or Riley, l996) are useful in the development of a campus wide plan to address mental health issues.

It is suggested that the final work product is a campus plan, focusing on the view of the institutional future and one that places significant priority on the current and future mental health, wellbeing, and work setting needs.

Incorporate Aspects of Campus Wide Mental Health Plan into Ongoing Activities

Plans are only useful if they influence institutional behavior. Only the president can insure the implementation of the plan. Having this issue on frequent cabinet meetings can facilitate moving from planning to action with a coordinated, all campus emphasis. Including the resources necessary in the normal budgeting process may require presidential directive. A campus wide messaging/marketing program will be needed to advise the campus of important actions in response to the mental health crisis. Campus wide periodic dissemination of mental health data serves to reinforce the importance of this priority.

In conclusion, the pandemic has provided both a need and an opportunity for each institution to address both the current mental health crisis and its future. Each institution will need to implement a strategy that is mission driven, data informed, and all-campus focused. This is now a seminal priority for the presidency.

References

Abrams, Z. (2020). A crunch at college counseling centers. APA Monitor. 51(6)

Amaya, M., Donegan, T., Conner, D., Edwards, J., & Gipson, C. (2019). Creating a culture of wellness: a call to action for higher education, igniting change in academic institutions. Building Health Academic Communities Journal. 3(2)1-36. https://doi.org/l0.1806/bhac.v3i2.7117.

Ameri, M., Daun. T. D., & Jetter, A, (2013). A review of scenario planning. Futures, 46,23-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2012.10.003

American College Health Association. (2022). The health campus framework. American College Health Association. Silver Spring, MD

American Council on Education (2022). College enrollment during the pandemic. Facts in Hand. American Council on Education. Washington, DC.

Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors. (2021). Annual survey: 2020. https://www.aucccd.org/assets/documents/Survey/2019-2020%20Annual%20Report%20FINAL%204-2021.pdf.

Bichsel, J., Fuesting, M., Schneider, J. & Tubbs, D. (2022). The CUPA-HR Employee Retention Survey: Initial Results. CUPA-HR. https://www.cupahr.org/surveys/research-briefs/higher-ed-employee-retention-survey-findings-july-2022/

Brantley, A., & Shomaker, R. (2021). What’s next for the higher education workforce? A look at the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. CUPA-HR. https://www.cupahr.org/issue/feature/whats-next-for-the-higher-ed-workforce/

Broton, K. M., Mohebali, M., & Lingo, M. D. (2022). Basic needs insecurity and mental health: community college students’ dual challenges and use of social support. Community College Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/00915521221111460

Brunner, J., Wallace, D., Keyes, L. N., & Polychronis, P.D. (2017). The comprehensive counseling center model. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 31(4) 297-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2017.1366167

Caron, C. (2022). Before heading to college, make a mental health checklist. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/08/well/mind/mental-health-college-students.html?smid=url-share

Carrasco, M. (2022). Overhauling mental health. InsideHigherEd. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/07/01/mental-health-overhaul-cal-state-long-beach

Center for College Mental Health. (2022). 2021 Annual Report. (Publication No. STA 22-132).

Chronicle of Higher Education & P3*EDU. (n.d.) 2022 Public-Private Partnership Survey. www. P3edu.com.

Chessman, H, M., Vigil, D., & Soler, M.C. (2020). Mental Health Task Forces in Higher Education. American Council on Education, Washington, DC.

Coleman, M. E., (2022). Mental health in the college classroom: best practices for instructors. Teaching Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X221080433

D’Andrea, V. (2008). Peer counseling in colleges and universities: a developmental viewpoint. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 1(3) 39-55. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J035v01n03_04

DeloitteU.S. (2020). COVID-19 higher education scenario planning. Deloitte Perspectives, www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/public-sector/articles/covid-19-higher-education-scenario-planning.html.

Donaldson, S. (2022). Why students quit college during Covid. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-students-quit-college-during-covid

Douce, L. A, & Kelling, R. P. (2014). A Strategic Primer on College Student Mental Health. American Council on Education. Washington, DC.

Dykes-Anderson, M. (2013). The case for comprehensive counseling centers at community colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 37(10) 742-749. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668921003723235

Edelman, J. (2022). Survey shows changing picture of campus mental health crisis. Diverse Issues in Higher Education. https://www.diverseeducation.com/students/article/15295567/survey-shows-changing-picture-of-campus-mental-health-crisis

Frank, J. (2022). Opinion: hiring more college mental health counselors is not the only or the best answer for today’s struggling students. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-hiring-more-college-mental-health-counselors-is-not-the-only-or-the-best-answer-for-todays-struggling-students/

Felix, E., Hanby, A., Griff, A., & Lorenzo, A., W. (2022). How college and universities can emerge from the COVID crisis stronger than before. Brightspotstrategy. https://www.brightspotstrategy.com/whitepaper/higher-ed-after-covid-19/

Greenfield, N. M. (2022). Why higher education is losing its luster as an employer. University World News https://universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20220809163426107

Grosch, J. W., Duffy, K. G., & Hessink, E. K. (1996). Employee assistance programs in higher education. Employee Assistance Quarterly. 11(4) 43-57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J022v11n04_03

Hadler, N. L., Bu, P., Winkler, A., & Alexander, A. W. (2021). College student perspectives of telemental health: a review of the recent literature. Current Psychiatry Reports 23(6). DOI: 10.1007/s11920-020-01215-7

Hanover Research. (2021). Higher education-scenario planning toolkit 2000-20001. HED WP420

Harris, B. R., Maher, B. M., & Wentworth, L. (2022), Optimizing efforts to promote mental health on college and university campuses: recommendations to facilitate usage of services, resources, and supports. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 49(2)252-258. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11414-021-09780-2

Haseltine, W. A. (2021). How peer counseling can address barriers to student mental health. FORBESHEALTH. https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamhaseltine/2021/08/09/how-peer-counseling-can-address-barriers-to-student-mental-health/?sh=1eb605641638

Higher Education Mental Health Alliance (HEMHA), (2019), HEMHA Guide: College Counseling from a Distance. http://hemha.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/HEMHA-Distance-Counseling_FINAL2019.pdf

Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D. (eds). (2021), INSIDE higher ed 2021 survey of college and university presidents. INSIDE Higher Ed & Hanover Research. https://www.insidehighered.com/booklet/2021-survey-college-and-university-presidents

Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D. (eds) (2022a). INSIDE higher ed 2022 survey of college and university chief academic officers. INSIDE Higher Education & Hanover Research. https://www.insidehighered.com/booklet/2022-survey-college-and-university-chief-academic-officers

Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D., (eds). (2022b). INSIDE higher ed 2022 survey of college and university business officers. INSIDE Higher Ed & Hanover Research. https://www.insidehighered.com/booklet/2022-survey-college-and-university-business-officers

Jaschik, S., & Lederman, D., (eds). (2022c). INSIDE higher ed 2022 survey of college and university presidents. INSIDE Higher Ed & Hanover Research. https://www.insidehighered.com/booklet/2022-survey-college-and-university-presidents

Katz, D. S., (2014). Community college student mental health: a comparative analysis. Community College Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552114535466

Kelly, R. (2022). Hybrid, whatever that means, will dominate the future of online learning. Campus Technology. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2022/08/09/hybrid-whatever-that-means-will-dominate-the-future-of-online-learning.aspx

Kniffin, K., Anseel, F., Ashford, S., Bamberger, P., Bhave, D., Creary, S., Flynn, F., Greer, L., Naraynan, J., Antonakis, J., Bakker, A., Bapuji, H., Choi, V., Demerouti, E., Gelfand, M. & Johns, G. (2020). COVID-19 and the workplace: implications, issues for future research and action. American Psychologist. 76(1)61-77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

Koenig, R. (2022). Is higher ed really to embrace hybrid learning? EdSurge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2022-08-09-is-higher-ed-really-ready-to-embrace-hybrid-learning

Lederer A, M., Hoban, M. T., Lipson, S. K., & Eisenberg, D. (2021). More than inconvenienced: the unique needs of U.S. college student during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health, Education & Behavior 48(1) 14-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120969372

Leonhardt, M. (2022). 14% of students say they dropped out of college because of mental health challenges. FORTUNEWell. https://fortune.com/well/2022/06/15/college-students-drop-out-of-college-mental-health-challenges/

Leonhardt, M. (2022). What colleges can do right now to help alleviate the mental health on campus. FORTUNEWell. https://fortune.com/well/2022/07/30/what-colleges-can-do-to-alleviate-the-mental-health-crisis-on-campus/

Lipson, S. K., Lattle, E. G., Elsenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by us college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007-2017). Psychiatry Serv. 70(1) 60-63. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800332

Luderman, D. (2022). Business officers upbeat despite major headwinds. INSIDE Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/survey/college-business-officers-upbeat-despite-worrisome-outlook

Maiden, R. P, & Phillips, S. B. (eds.). (2008). Employee Assistance Programs in Higher Education. Routledge. ISBN 9780789036995

Malanson, J.J. (2022). A collaborative approach to COVID-19 planning at a regional public university. Metropolitan Universities, 33(1), 55-63. https://doi.org/10.18060/25279

Mary Christie Institute. (2021). The role of faculty in student mental health. Mary Christie Institute White Paper. https://marychristieinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-Role-of-Faculty-in-Student-Mental-Health.pdf

Mary Christie Institute. (2022). Peer counseling in college mental health. Mary Christie Institute. https://marychristieinstitute.org/reports/peer-counseling-in-college-mental-health/

Meeks, K., Peak, A. S., & Dreihaus, (2021). A. Depression, anxiety, and stress among students, faculty, and staff. Journal of American College Health. 10.1080/07448481.2021.1891913

Melnyk, B. M., Tan, A., Hsieh, A. P., Regan, E. P., & Stanley, L. (2021). Beliefs, mental health, healthy lifestyle behaviors and coping strategies of college and university faculty and staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health. 10.1080/07448481.2021.1991932

Mitchell, S. L., Oakley R., D., & Dunkle, J. H. (2019). White paper: a multidimensional understanding of effective university and college counseling center organizational structures. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy 33(2) 89-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2019.1578941

Moody, J. (2022). A 5th straight semester of enrollment declines. InsideHigherEd. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/05/26/nsc-report-shows-total-enrollment-down-41-percent

Moody, J. (2022). Higher ed’s hiring woes. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/07/21/hiring-woes-loom-large-business-officers-conference

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2021. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Wellbeing in Higher Education: Supporting the Whole Student. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26015/mental-health-substance-use-and-wellbeing-in-higher-education-supporting

Peacock, J. (2022), University employees’ perceptions of health during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Further and Higher Education. 46(1) 107-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1887464

Riba, M. B., Malani, P. N., Ernst, R., & Parikh, S. (2022). Mental health on college campuses: supporting faculty and staff. Psychiatric Times.

Rieley, J. B. (l996). Scenario planning in higher education. Project Organizational Effectiveness. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234589223_Scenario_Planning_in_Higher_Education

Rosenbaum, P. J., & Oakley, D. (2020). Thoughts about the possibility of return: exploring the potential of new college life. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 3:3, 173-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2020.1797428

Schiemann, M. (2021). Reimagining support for mental health: what higher education leaders can do. AGB Blog. https://agb.org/blog-post/reimagining-support-for-mental-health-what-higher-education-leaders-can-do/

Schwitzer, A. & Sixbey, M. (2022). Delivering college telehealth, telemental health, and telemental health, and telesupport today—looking back to look forward. About Campus. 26(6) 13-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/10864822221082696

Sontag-Padilla, L. (2020). College students need mental health support. The RAND Blog. https://www.rand.org/blog/2020/10/college-students-need-mental-health-support.html

Soria, K. M. & Horgos, B. (2021). Factors associated with college students’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, Journal of College Student Development. 62(2) 236-242. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2021.0024

Spitalniak, L. (2022). Student affairs workforce faces retention issues, report says. Higher Ed Dive. https://highereddive.com/news/student-affairs-workforce-faces-retention-issues-report-says-1/621127/

Spitalniak, L. (2022). Stress prompts 76% of 4-year college students to weigh leaving, survey finds. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/stress-prompts-76-of-4-year-college-students-to-weigh-leaving-survey-find/622330/

Spitalniak, L. (2022). Colleges use teletherapy to support students outside of the academic year. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/colleges-use-teletherapy-to-support-students-outside-of-the-academic-year/625532/

Spitalniak, L. (2022). 3 in 5 higher education employees feel unheard at work, survey says. Higher Ed Dive. https://www.highereddive.com/news/3-in-5-higher-education-employees-feel-unheard-at-work-survey-says/628934/

The Jed Foundation. (2021). Jed’s Comprehensive Approach to Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention for Colleges and Universities. https://www.jedfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/JED-Comprehensive-Approach_FINAL_July19.pdf

The Jed Foundation/EDC. (2011). A Guide to Campus Mental Health Action Planning. https://jedfoundation.org/campus-mental-health-action-planning-guide/

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2016). Learn the eight dimensions of wellness. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma16-4953.pdf

Taylor, M., Sanchez, C., Turk, J. M., Chessman, H. M., & Ramos, A. M. (2021a). College and university presidents respond to COVID-19: 2021 spring survey. American Council on Education/TIAA Institute. Washington, DC.

Taylor, M., Sanchez, C., Turk, J. M., Chessman, H.M. & Mamos, A.M. (2022b). College and university presidents respond to COVID-19: spring term survey, part II. American Council on Education/TIAA Institute. Washington, DC

The Healthy Minds Network. (2020). College Student Mental Health Action Toolkit on Mental Health Data & Statistics. Healthy Minds Network/Active Minds/the Jed Foundation (JED). https://jedfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/CollegeStudentMentalHealthActionToolkit.pdf

Travia, R. M., Larus, J. G., Andes, S., & Gomes, P. G. (2020). Framing wellbeing in a college campus setting. Journal of American College Health. 70(3)758-772. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1763369

Trela, K. (2008). Facing mental health crisis on campus. About Campus 13(1)30-32. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.237

Vespia, K. M. (2007). A national survey of small counseling centers: successes, issues, and challenges. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 22(1), 17-40. https://doi.org/10.1300/J035v22n01_03

Waters, K. A. (2022). Teleworking: how understanding its history will benefit institutions today. College and University. 97(3)65-70.

Wawrzynski, M. R. & Lemon, J. D. (2021). Trends in health and wellness peer education training: a five-year analysis. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice. 58(2) 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2020.1853554

West, C. (2022). Heavy pressure; Student mental health needs grow. AGB Trusteeship, 30(2), 1-14. https://agb.org/trusteeship-article/heavy-pressure/

Wilcox, K., & Stiles, R. (2017). Thriving at the liberal arts colleges: key issues, service models, and research for mental wellness. 2017 Grinnell College ‘Thriving Conference presentation. https://download.hlcommission.org/lumina-resources/KeyIssuesServiceModelsandResearchforMentalWellness.pdf

Wiest,L. R. & Traecy, A. C. (2019). Faculty preparation to work with college student with mental health issues. Educational Research: Theory and Practice. 30(1), 46-50

Winfield, J. D., & Paris, J. H. (2022). Burnout and working conditions in higher education during COVID-19: recommendations and policy and practice. College and University. 97(3) 61-63.

Yakoboski, P., & Fuesting, M. (2022). Responding to job hunting among higher ed employees. TIAA Institute. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4264988

Zahneis, M. (2022). Higher ed is looking to refill jobs, but it’s finding a ‘shallow and weak’ candidate pool. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 68(24). https://www.chronicle.com/article/higher-ed-is-looking-to-refill-jobs-but-its-finding-a-shallow-and-weak-candidate-pool