The Climb to the Top: Advice for Aspiring Black and African American College and University Presidents

Quincy Martin III

Matthew A. Cooney

Governors State University

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Dr. Quincy Martin III, Assistant Professor, College of Education, Governors State University, 1 University Parkway, University Park, IL 60484, email: qmartin@govst.edu

Abstract

The purpose of this paper was to provide practical advice on how Black and African American college and university presidential aspirants may adequately prepare themselves for such a pivotal leadership role. Seven Black and African American college and university presidents from a variety of institutional types (community colleges, four-year institutions, Predominately White Institutions [PWI], and Minority-Serving Institutions[MSI]) across the United States answered a simple question: What advice can you offer to aspiring Black and African American college and university presidents to adequately prepare them for this leadership role? The authors supplemented their responses with highlights of professional development opportunities for aspiring Black and African American college and university presidents to consider as part of their career trajectory.

Managing the leadership of higher education institutions in contemporary times has become an arduous task and the success of these institutions is primarily determined by the wisdom and leadership employed by an institution’s president. Within their colleges and universities, presidents are regarded as the focal point of leadership. They are expected to provide quality leadership skills, personify values needed in the institutions, and mold the institution’s policies accordingly. Outwardly, the presidents are the institution’s primary ambassadors; they act as college and university representatives and advocates. In order to translate an institution’s vision and strategic direction for a variety of stakeholders, presidents must be skilled and proficient in the language of business, nonprofit, philanthropy, and government as well as the language of the academy (Aspen Institute, 2017). Accordingly, the fundamental features of a president’s legacy are to uphold the institution’s image, dignity, and competitiveness in the outside world as well as employ critical inputs that are needed to run a successful higher education institution.

Fundamentally, a higher education institution presidency is driven by vision-oriented leadership that sets smart, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timely goals for its campus. The modern higher education institution’s environment makes it highly complicated for institutional presidents since it is punctuated with extensive cultural, racial, socio-economic, political, and religious differences among campus communities. These differences require highly dynamic, flexible, accommodative, firm, and comprehensively updated presidents. As higher education institutions evolve, so do the faces that lead them.

Background of Study

Different colleges and universities require diverse presidential skills based on institutional factors such as the institutional mission and size. A fundamental tool of leadership understands, over generations, that leadership is an aspect of perseverance. After the American Civil War, the social forces developed strong personalities with innate abilities to direct the social pressures of American institutions of higher learning (American Council on Education [ACE], 1937). The selection of the presidents within these institutions relied on challenges affiliated with each particular institution. On that note, it is prudent to characterize the presidents based on their institutions’ distinctive attributes. Among the contextual principles generated among scholars and administrators alike include intimate abilities to grow against the complex modern diverse higher learning environment (McClellan & Stringer, 2016). The focus was to instill the needed skills, mental stamina, and physical prowess to ensure they are psycho-socially, physically, and skillfully baked to face the complicated post-war life (ACE, 1937). The premise of this engagement has not changed much over the years in higher education institutional leadership.

The presidency needs diversification, and diversity in the presidency will become more critical in the future, as it is fueled by the increasing demographic shifts in the nation’s student body. It is observed that ethnic or racial minorities received low representation in presidential posts. Racial or ethnic minorities were represented by less than 17% percent of the presidents (ACE, 2017). Further, 25% of the presidents had held the position previously (ACE, 2017). It was also noted that institutions prioritized selecting experienced presidents, which would tilt the candidates’ pool to favor white men, which does not promote diversification of the presidency. Undoubtedly, presidents indicated the relevance of promoting diversification in the leadership pipeline and higher education. Accordingly, most presidents maintained that it was essential to carry out efforts to eradicate racial bias in institutional procedures and policies (ACE, 2017).

About 54% of presidents are projected to depart from their positions in less than five years, which would provide a relevant opportunity for the acceleration of diversifying the presidency (ACE, 2017). As a result, it is with certainty that policies and strategies that promote diversification of the presidency should be implemented and developed with devotion; hence, the premise of this paper.

Advice for Black and African American College President Aspirants

This paper seeks to provide career guidance for Black and African American professionals who aspire to become a college or university president. The authors engaged in two different methods to capture advice for aspiring Black and African American college presidents. First, the authors utilized their professional networks to locate Black and African American college presidents and ask a simple question: What advice can you offer to aspiring Black and African American college and university presidents to adequately prepare them for this leadership role? Next, the authors presented key professional preparation practices that scholars noted are important for Black and African American college presidents to advance to the presidency. The inclusion of literature, as well as the advice directly from college presidents, provides an overview of wise and prudent guidance for presidential aspirants.

Advice from Black and African American College Presidents

The aim of this qualitative research study was to provide advice on how Black and African American college and university presidential aspirants may adequately prepare themselves for such a pivotal leadership role. The advice from the participants will potentially stimulate presidential aspirants to provide deep, critical thought to determine and underscore if the presidency is ultimately a leadership path they should consider. As such, the authors contacted Black and African American presidents who currently lead a two-year or four-year, accredited, higher education institution. The presidents were approached using e-mail or personal contacts to obtain consent to participate at a time that was mutually convenient for them and the researchers. As one primary question guided this study, participants were provided the opportunity to respond via email, phone, or web conference. Each participant was asked to answer the following question: What advice can you offer to aspiring Black and African American college and university presidents to adequately prepare them for this leadership role?

Participant and Institutional Profiles

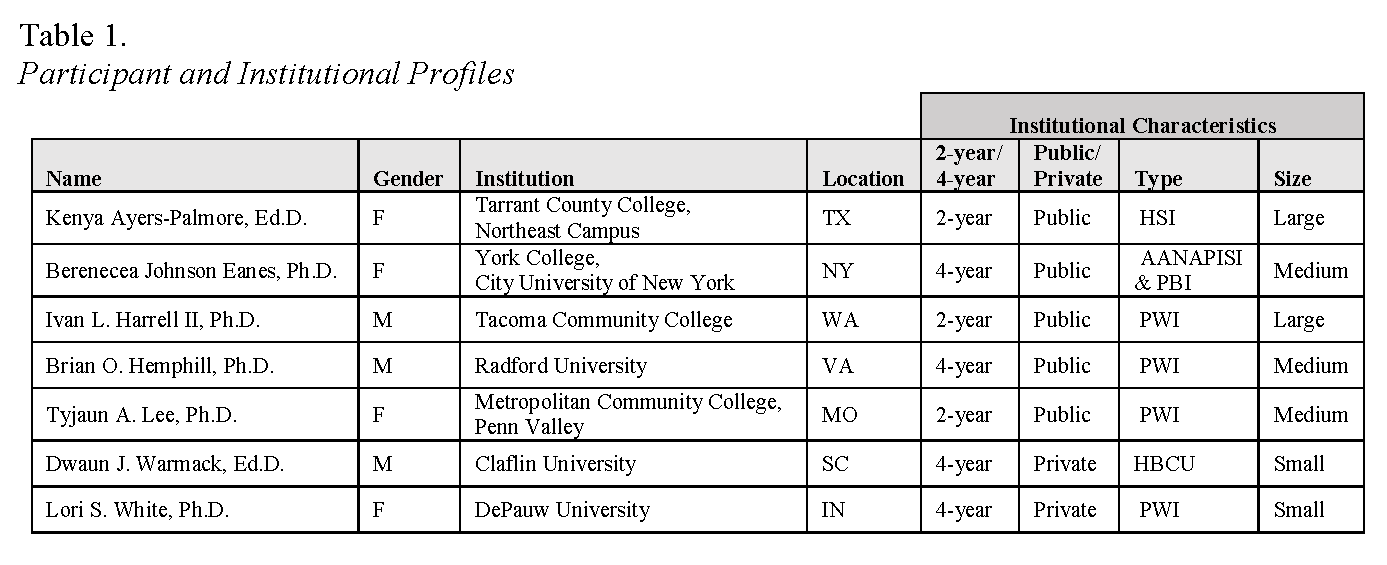

Although the terms chancellor and president may be designated as the chief executive officer for a higher education institution, all participants in this study hold the title of president at their respective institutions. There were a total of seven Black and African American college and university presidents who participated in this study. A brief profile of the participants and institutional characteristics were obtained to highlight demographic information that included name and gender of participants, the institutions they lead and are located, and institutional characteristics (see Table 1). The seven participants were selected from a population of current higher education institution presidents from across the United States. Each participant agreed to have their names and institutional affiliations made public in the study. Although most participants in the study serve at Predominately White Institutions (PWI), it is important to note the specific designation of Minority-Serving Institutions (MSI) in this study. One participant serves at a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) and another serves at a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI). The final participant serves at an institution that is classified as both an Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institution (AANAPISI) and a Predominantly Black Institution (PBI). In terms of institutional size, the participants’ institutions were selected based on using the definitions provided by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education.

Responses

Each participant responded to the primary question: What advice can you offer to aspiring Black and African American college and university presidents to adequately prepare them for this leadership role? Participants provided a variety of thought-provoking pieces of advice for presidential aspirants that centered on several collective principles. Firstly, a focus on mission was highly regarded from the viewpoint of aligning both personal mission and institutional mission. Secondly, there was emphasis placed on the avoidance of chasing the title of president, but instead, providing passion and focus on the actual work that the title can bring. Thirdly, the importance of being self-reflective and authentic provides presidents the ability to more easily build trust and be their genuine selves. Fourthly, relationship building was noted as a staple to building support with a variety of internal and external campus stakeholders. Lastly, participants underscored the immense time commitment the position can entail along with the need to continuously work harder than others.

As some participants discussed a crossover of themes within their remarks, each participant’s comments were not disaggregated in an effort to avoid disrupting the context or flow of their remarks. Participant responses are listed by last name in alphabetical order.

Kenya Ayers-Palmore, Ed.D.

President, Tarrant County College Northeast Campus

Let a laser focus on your students’ potential be your NorthStar. Be in love with the students, the mission and the work that supports the institution…not with the title. The pivotal work of the presidency does not happen in the limelight. It happens through listening, negotiating, and coalition-building –in lots and of meetings and in hours far beyond a typical 9-5 workday. The role requires that you embrace being a connector of people and opportunities. Relational excellence will be vital as you build the ecosystems essential for 21st century presidential leadership.

Berenecea Johnson Eanes, Ph.D.

President, York College, City University of New York

There are a lot of nuances to being a college or university president. It’s learning early on about all of the different possibilities and then being self-reflective enough to say to yourself ‘What is the best fit for me? What do I really want to do? What’s my mission and my vision? Who do I want to help?’ And, then also just remembering that they’re 24/7 jobs. These are not jobs that you ever get a day off, even when you’re on vacation. You take vacation the best you can, you have the best team that you can–just making sure that you are physically, emotionally, and financially ready to be in this kind of position. You want to be as confident going into your role as possible, but remembering if you’re a first time president that you’ve never done this job before. You have to be willing to be the authority and be learning at the same time. And, that is something that you have to work on, on a daily basis.

Ivan L. Harrell II, Ph.D.

President, Tacoma Community College

Develop a clear understanding of who you are as an individual and stay true to that during your presidency. Being a college president is one of the most fulfilling roles anyone can have, but it is also accompanied by the obligation to address the needs and desires of such a diverse constituency, including students, faculty, staff, trustees and the broader community. During my short tenure, I have learned that being truly authentic at all times and with all groups allows people to better understand who you are, what you stand for, and can lead to greater trust. This allows for the development of strong(er) working relationships that result in a positive impact on the college as a whole. Just remember, always be YOU!

Brian O. Hemphill, Ph.D.

President, Radford University

Be engaged and stay focused! Higher education is a calling and profession that you enter due to a strong desire to serve others and create opportunities for current and future generations. With that being said, in leadership roles, challenges are constant, and interruptions are inevitable.

Never lose sight of your personal mission by remaining steadfast in your beliefs and unwavering in your pursuits.

You will make countless mistakes, but you will learn a great deal about yourself and others in the process. Those early mistakes and life lessons will serve as the foundation and inspiration for your success. Above all else, you should pursue excellence, but never perfection.

There will always be someone who is more gifted in certain areas than you, but never let anyone out work you!

Tyjaun A. Lee, Ph.D.

President, Metropolitan Community College-Penn Valley

Be clear about your intentions. The Presidential seat is not for the faint of heart, but for individuals who can be vulnerable, make unpopular decisions and love their faculty, staff, and students that will ultimately meet the mission of the institution.

Dwaun J. Warmack, Ed.D.

President, Claflin University

Blossom Where You Are Planted! So often individuals are focused on getting to the seat (presidency), but not focused on developing the core competencies needed to remain in the seat. Do not chase the position, but chase your passion … then rest will take care of itself!

Lori S. White, Ph.D.

President, DePauw University

I actually never imagined or planned becoming a college president. I was encouraged to pursue the opportunity by several mentors. I have found the best preparation has turned out to be my many years as a Vice President for student affairs. The accompanying complex leadership and management responsibilities as a VPSA of multiple departments, budget and personnel oversight, along with being the point person for understanding, developing and promoting the student experience and coordinating crucial incident responses have been very helpful in my role as president. My preparation for the presidency was also strengthened by having spent time prior working in academic affairs and in all of my administrative positions holding adjunct, clinical or professor of practice appointments on the faculty. Finally, a good president must have great communication and relationship building skills; understand higher education finance and enrollment management (and student demographic trends); be unafraid to ask for money (and other forms of support from stakeholders); be able to make tough decisions when necessary; be passionate about the WORK of being president not just motivated by the TITLE; believe deeply in the mission of your institution, and understand as president you become the embodiment of the hopes and dreams of your institution’s students, faculty, staff and alumni.

Advice from Higher Education Literature

There are numerous professional development opportunities dedicated to diversifying the college and university presidency. The American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) hosts the Millennium Leadership Initiative (MLI) which focuses on skill development and networking for aspiring college and university presidents from traditionally underrepresented groups in higher education. The program was first conceptualized in July 1998, and the first MLI institute was held in 1999 as a result of AASCU leaders committing to intentional professional development experiences to nurture and diversify the college and university presidency (AASCU, 2018). Within the first 21 years of the program, over 570 professionals graduated from the program and 104 graduates became college or university presidents. Similar to the MLI program, there are programs designed to prepare aspiring college and university presidents at Minority-Serving Institutions.

Three of the presidents that were interviewed lead Minority-Serving Institutions. The Center for Minority Serving Institutions at Rutgers University hosts the MSI Aspiring Leaders program that is designed for mid-level professionals who aspire to obtain a presidency at Minority-Serving Institutions (Center for MSIs, n.d). Similarly, the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities presents La Academia de Liderazgo, which aims to prepare senior leaders at Hispanic-Serving Institutions and Emerging Hispanic-Serving Institutions. (HACU, n.d.). The aforementioned programs often have a formal mentoring component which is an important tool in diversifying the college and university presidency.

Black and African American college and university presidential aspirants should consider participating in formal or informal mentoring relationships as a way to prepare for the position (Commodore et al., 2016). Mentoring relationships have assisted aspiring college and university presidents with preparing for the position, advocating for the mentee’s professional development, and encouraging them to apply for president positions (Briscoe & Freeman, 2019). Additionally, mentoring relationships amongst college presidents of color provided psychosocial support and expanded their professional development opportunities (Chang et al., 2014). It is important to note that there is no single best way to prepare for a college or university presidency and Black and African American college and university presidential aspirants should consider the advice from the sitting presidents interviewed as well as the research presented.

Discussion

Although the readiness of first-time college and university presidents may be questioned by some, most new presidents are prepared. A study by Selingo et al. (2017) noted that approximately two-thirds of presidents reported being groomed by mentors or coaches to prepare for their roles ahead. However, only a third indicated that they continue to receive mentoring and coaching to thrive in their tasks.

The environment of operation for college and university presidents is one of chaos and uttermost complexity. A variety of conflicting decisions have to be made, each with an outcome not easily predictable. Despite all that, college and university presidents face extensive scrutiny and are expected to provide best-analyzed decisions. Furthermore, they have to overcome these challenges in a constantly changing environment while still being answerable to their superiors’ decisions. The presidents are expected to bring new light into the institutions by providing new reform methods while embodying institutional values and policies. The presidents also need to showcase themselves as a familiar figure to the campus while still maintaining good relations with the stakeholders—which can be exceptionally challenging and demanding. With their role open to change so often, the presidents’ long-term success could potentially be available to question. There has been increasing drift and gap between the quality of the skills rendered in higher education institutions and the demand in the recent past job market. Given this information, it is of utmost importance that presidential aspirants consider the advice of successful college and university presidents in order to improve their judgements, build confidence, and mitigate potential risks of questionable decision making that could lead to consequential long term results that have a negative impact on their career.

References

American Association of State Colleges and Universities. (n.d.). Influence and impact: The meaning and legacy of the millennium leadership initiative. https://www.aascu.org/MLI/20thAnniversary.pdf

American Council on Education. (2017). The American college president study. Washington, DC: Author.

American Council on Education. (1937). The student personnel point of view. Washington, DC: Author.

Aspen Institute. (2017). Renewal and progress: Strengthening higher education leadership in a time of rapid change. Washington, DC: author. Retrieved from http://highered.aspeninstitute.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/05/Renewal_Progress_CEP_05122017.pdf

Briscoe, K. L., & Freeman, S. (2019) The role of mentorship in the preparation and success of university presidents. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 27(4), 416-438. https://doi/org/10.1080/13611267.2019.1649920

Center for MSIs. (n.d). MSI aspiring leaders. Rutgers University. https://cmsi.gse.rutgers.edu/aspiring-leaders

Chang, H., Longman, K.A. & Franco, M.A. (2014) Leadership development through mentoring in higher education: A collaborative autoethnography of leaders of color, mentoring & tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 22(4), 373-389. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2014.945734

Commodore, F., Freeman, S., Gasman, M., & Carter, C.M. (2016). “How it’s done”: The role of mentoring and advice in preparing the next generation of historically black college and university presidents. Education Sciences, 6(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6020019

Goodwin, D., Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2019). Ethical issues in qualitative research. In C. Pope & N. Mays (Eds.), Qualitative research in health care (4th ed., pp. 27-41). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch3

Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities. (2019). HACU leadership academy/la academia de Liderazgo. https://www.hacu.net/images/hacu/OPAI/La%20Academia/2020LeadershipAcademyProgram_Brochure[1].pdf

Johnson, R.B., & Christensen, L. (2017). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. SAGE Publications, Inc.

McClellan, G. S., & Stringer, J. (Eds.). (2016). The handbook of student affairs administration (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Selingo, J., Chheng, S., & Clark, C. (2017). Pathways to the university presidency: The future of higher education leadership. Retrieved from: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/3861_Pathways-to-the-university-presidency/DUP_Pathways-to-the-university-presidency.pdf