Crafting the Message: The Complex Process Behind Presidential Communication in Higher Education

Jon McNaughtan

Texas Tech University

Patricia Ryan Pal

Texas Tech University

Correspondence related to this article should be directed to Dr. Jon McNaughtan, Assistant Professor of Educational Psychology and Leadership, Texas Tech University, at Jon.Mcnaughtan@ttu.edu

Abstract

University presidents engage in formal and informal communication through multiple modes of communication. While scholars have studied the content and motivations behind presidential communication, this study provides insight into the process that university presidents engage in when crafting public statements. Utilizing interviews with presidents (8) and vice-presidents of communication (4) at U.S. flagship universities, we employ the cognitive process writing theory to develop a process model of presidential communication, while highlighting how presidents describe their experiences crafting communication. Results highlight the president’s perception of their role as instigator of communication, the involvement of other senior leaders (e.g., legal counsel, chief of staff, etc.), and insight into the complex process of creating presidential communications. Implications include the need for presidents to develop their own formal communication process, the importance of being intentional with who communicates, and the need to develop communication teams to craft messages.

According to the American Council on Education’s College Presidents survey conducted in 2016, presidents claimed fundraising, crisis management, and government relations were three of the top four areas they felt least prepared (Gagliardi, Espinosa, Turk, & Taylor, 2017). In each of these areas, communication is critical and expectations on the timeliness of the communication continue to shorten (McNaughtan & McNaughtan, 2019). For example, in times of campus crisis, the ability of the president to calm their constituents often prevents exacerbating the situation (McNaughtan, Garcia, Lertora, Louis, Li, Croffie, & McNaughtan, 2018). Similarly, as presidents seek to raise money and work with elected officials, their communication skills are important to cultivate and secure major gifts (Hodson, 2010).

In contrast to formalized communication from the president, like inaugural addresses or state of the university speeches, most of the communication that presidents do is connected to impromptu activities of the president, like crisis communication and engaging with campus and community stakeholders. When focusing on this context driven communication that presidents engage with, much of the current research is focused on why presidents choose to communicate (Legon, Lombardi, & Rhoades, 2013; McNaughtan & McNaughtan, 2019) and what is included in their messages (McNaughtan et al., 2018; Vitullo & Johnson, 2010). The purpose of this study is to provide insight into the process of crafting presidential communication with specific focus on the presidents’ perspectives of their role in crafting communication, who they engage in the process, and what is entailed in the perceived role of those involved in the process.

Communication Skills and the College President

Despite limited information on the process of crafting presidential communications, the ability to communicate effectively has been identified by various sources as a key competency for a sitting college or university president (e.g., American Association of Community Colleges; 2013; Freeman & Kochan, 2013; Plinske & Packard, 2010). Smith and Wolverton (2010) confirmed the importance of communication as a competency for higher education leaders in a study of 295 senior higher education administrators (i.e., athletic directors, senior student affairs officers, chief academic affairs officers), noting the importance of both written and oral communication as well as including others in decision making. Similarly, a qualitative study of 13 presidents at four-year institutions found that effective communications were needed to the ensure the success of presidents (Freeman & Kochan, 2013). Particularly, the skill of writing and speaking to diverse audiences (e.g., faculty, students, and community) was noted as critical.

Selingo, Chheng, and Clark (2017) further argued that the development of communication skills on the pathway to the university presidency is a necessity for success, noting, “Presidents must be accessible and responsive, but also measured and restrained in an era driven by 24/7 news coverage and the inflammatory nature of social media” (p. 2). In their work, which included surveys from 165 presidents at four-year colleges and universities (112 private and 51 public institutions), the researchers found being a strong communicator/storyteller was the second most important skill needed for a new president assuming office, with the first being strategic thinking. Other skills which participants perceived as necessary for the role, such as fundraiser and collaborator, may in fact be influenced by the ability to communicate effectively, further highlighting its importance.

As a process, communication itself is complex as it involves transferring meaning from one individual to others, which is further complicated by the context that the communication is occurring that tends to change the original intent of the message (Barrett, 2014). Given the variety of settings that presidents communicate in ranging from impromptu speeches and comments (e.g., daily interactions, emails, informal meetings and events, blogs, tweets) to prepared formal remarks (e.g., formal response emails, speeches, media items), it is no surprise that the college presidential communication process is understudied. Even over the last decade, presidents have had to confront rapidly changing modes of communication, as seen in Barnes and Lescault’s (2013) work which explored social media usage among college and university presidents. The researchers found that over half of their sample of college and university presidents used Facebook (58%) or Twitter (55%), significantly outpacing other CEOs such as those at Fortune 500 companies (8% Facebook and 4% Twitter).

Focusing on the who in the crafting of communication, Zaiontz (2015) analyzed the use of social media for college and university presidents. Even in regards to informal communication channels, there are multiple models for how presidents communicate and create content, which Zaiontz groups into three categories: ghostwriters, hybrid, and independent. The ghostwriter model is when a president uses either staff from his or her office or communication team (e.g., vice president of communication) to create content and messages, often either making it explicit that the president was not involved in the creation of the content or leaving it ambiguous. Presidents, however, often found the ghostwriter model to be disingenuous and ineffective. In the hybrid model, presidents and their staffs collaboratively create content and communications. Instead of passing communication duties onto others, this method delegates when appropriate, but involves the president as the driving force. In the final model, the one most often used by presidents in Zaiontz’s study, presidents independently create the content for their social media accounts. Still, presidents who used the independent model engaged members of their staff, such as communications offices, in discussions about the potential content, especially if it was something that was sensitive or divisive.

Similar to the presidents in Zaiontz’s (2015) assertion that others should be included in deciding what to communicate about challenging or divisive topics, Pierce (2012) suggested in her primer on the college presidency that presidents should use caution when speaking on topics which may be complex or controversial as their words represent not just them, but the university. In a study of new college and university presidents’ communication, Smerek (2011) argued that these leaders are often drawn to what he deems “safe harbors” (p. 83), defined as sticking to broad or ambiguous goals in order to avoid contentious situations.

Failure to communicate effectively in almost any situation, but especially in times of discontent, could contribute to the end of a presidency, as evidenced by the body of work compiled by Trachtenburg, Kauver, and Bogue (2013) in which interpersonal skills, such as communication skills, were a key theme in the derailment presidents across institutional types. At master’s level institutions, for instance, three out of four failed presidents struggled with communication, which created challenges cultivating relationships with key constituents (Longmire, 2013). In another example, McNeal (2013) highlighted a case in which a president lacked communication skills necessary to share pertinent information with the college community and board. This lack of communication and attempt to control all information and how it was released eventually contributed to the downfall of his presidency. These examples of failed presidencies showcased the critical necessity of strong communication skills in order for individuals to be successful in a college president role.

Other CEOs and Leadership Communication

With limited research on how college and university presidents craft communications for dissemination to stakeholders, looking to research on CEOs in business provides an additional perspective. The importance of the words of the CEO, much like those of a university or college president, were highlighted by Amernic and Craig (2007a), who noted, “In an era of heightened corporate accountability…CEOs frequently need to be reminded of the power of CEO-speak—the language they use in speeches, letters to shareholders, press releases, and other written communications” (p. 65). In a discussion on whether or not CEOs wrote their own letters using media statements from some prominent CEOs, Amernic, Craig, and Tourish (2010) noted that many CEOs either write their own letters or direct professional writers on the content and tone of the message to be crafted. They further explained:

It is much more defensible to argue that the thinking and issues infusing the CEO’s letter are determined primarily by the CEO, and that they are indicative of the CEO’s mindset – irrespective of whether or not the letters are crafted in their entirety personally by the CEO or by a ghost writer. (p. 29)

Part of the reason that CEOs need to be involved so intimately in what is written on their behalf is that their signature appears on it, appearing to stakeholders that even if they did not personally write the words, they believe in them, making them responsible for what is in the communication.

In their work on CPA/CFO involvement in CEO messages surrounding finance and accounting, Amernic and Craig (2007a) suggested that CPAs and CFOs should be involved in crafting messages for CEOs to ensure that words and images used convey the appropriate meaning. Top management of organizations should be involved in the development of CEO communications in multiple ways including monitoring the communications in general and providing feedback and advice on content and language use in order to provide stakeholders with an accurate depiction of what is happening within the organization (Amernic & Craig, 2007b).

For some CEOs, the use of professional speechwriters or ghostwriters help them to convey their meaning and tone in written communication and speeches while allowing them to focus their time on other aspects of their job. In Seeger’s (1992) review of literature, he noted three assumptions surrounding ghostwriters in the corporate world: (1) CEOs have too many other responsibilities to focus on writing speeches for stakeholders; (2) ghostwriters are not coming up with the content, but rather framing the ideas of the CEO; and (3) audiences are aware that CEOs typically do not write all communications that come out. Using others to help craft corporate communications also serves to expand how CEOs and leaders can connect with diverse and culturally distinct audiences in various forms of media (e.g., print, news, social media, videos; Knapp & Hulbert, 2017). Public relations or communications teams can help CEOs craft a message that is consistent and cohesive with the work of the corporation. However, there is criticism when CEOs use ghostwriters and professional communication staff to draft informal communications that are often meant to be personal, such as a tweet or a blog. Knapp and Hulbert’s discussion on ghostwriters highlights that within the corporate realm, the type of message helps to contribute to how it is crafted.

Theoretical Framework

This study utilized the cognitive process theory of writing to structure the analysis and as the foundation to develop a conceptual framework for how presidential communication is crafted (Flower & Hayes, 1981). As initially put forth, cognitive process theory is focused on the how individuals engage the writing process, and was one of the first theoretical frames put forth to dispel the notion that writing was a linear process composed of prewriting, writing, and editing (MacMillan, 2012). This advance in the way that writing occurs allowed scholars to introduce additional complexities into the process, such as contextual influences (Hayes, 2006) and the role of audience in the crafting of messages (Bereiter & Scardamlia, 1987).

In its basic form, the cognitive process theory for writing identifies four distinct aspects (Flower & Hayes, 1981). First, writing is an organized act that involves a number of decisions and thought processes. This aspect of the writing process is useful to understand how individuals engage with their contexts, and experiences while crafting writing. Zimmerman and Risemberg (1997) argue that this aspect of the process is controlled by the writers previously developed habits, beliefs, and environment. In the case of higher education, the complexity of institutions and the need for a team of college or university leaders provide one aspect of this context.

Second, Flower and Hayes (1981) posit that the writing process is hierarchical in nature, meaning that each decision, or embedded process, informs and dictates the next part of the process. Recent scholarship on the cognitive process of writing has focused on how throughout writing, our decisions overlap and inform next steps (Perrin, 2006; Perrin & Wildi, 2010). This cyclical process is inherently difficult to measure or follow, as it assumes that not all processes will be the same.

The third aspect of the cognitive process theory for writing is that the act of composing communication is goal oriented, which means that writers have purpose in their composition. This part of the process is especially critical in this study, as past research on presidential communication has found that presidents are motivated to communicate by institutional values (McNaughtan & McNaughtan, 2018) and external events that impact their constituents (McNaughtan, Louis, Garcia, & McNaughtan, 2019). In their role as sensemakers for their constituents, goal orientation and purpose is a critical aspect of the writing process (Eddy, 2003, 2005).

Finally, Flower and Hayes (1981) argue that as writers engage in the process their main goal begins to be supported by smaller goals related to different aspects of the writing process. This aspect of the process is important as it illustrates how writing is an iterative process that evolves, as the writer engages with a specific topic, or with additional perspectives. Specifically, the original intent for writing may not be the only goal by the end.

Much of the research on presidential communication has focused on the motivation for the message (McNaughtan & McNaughtan, 2019; McNaughtan et al., 2019), the framing of the message (Smerek, 2011), and how the message can inform recipients (Eddy, 2003, 2005). The cognitive writing process theory of writing (Flower & Hayes, 1981) provides a way to think more intentionally about how communication is initiated and developed by presidents in higher education.

Purpose of the Study

Given the dominant focus of presidential communication literature on crisis communication (e.g., Cole, 2015; Len-Ríos, 2010; Vitullo & Johnson, 2010), message content (McNaughtan et al., 2018), characteristics of the messenger (Bastedo, Samuels, & Kleinman, 2014), and the motivation for communicating (McNaughtan & McNaughtan, 2019; Papadimitriou, 2018), there is a need to understand the actual process of communication. Even basic questions such as who is involved and how do presidents decide who to engage when crafting communication, are seemingly left to anecdotal understanding. Building on past research focused on the communication process of university leaders and CEOs in business, the goal of this study was to provide insight into the perceived role of the president and develop a modified cognitive process of communication theory to inform how presidents in higher education engage in developing communication. Our study was guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1: How do university presidents perceive their role in the communication process?

- RQ2: Who is involved in the process of crafting presidential communication, and what is their role?

Data and Methods

A qualitative approach was selected for this study as it allowed the researchers to explore and interpret the meaning of the experiences and perceptions of presidents and vice presidents at flagship universities regarding the presidential communication process (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). Specifically, this study utilized a collective case study methodology (Stake, 2008) to examine the process of crafting communications by presidents (8) or vice-presidents (4) at flagship universities across the United States. Creswell and Poth (2018) suggested that an individual case can be a decision process, such as the process used to create and disseminate communications to constituencies both on and off campus. A case study, according to Merriam (1998), is an “intensive, holistic description and analysis of a bounded phenomenon” (p. xiii). The cases were bounded by the leadership level (presidents/vice presidents), process (crafting a communication), and institution type (flagship universities).

A purposeful sample of participants was identified using National Center for Education Statistics (2016) data based on institutional type as a flagship university (See Appendix A for list of flagship institutions). We requested an interview from all 50 flagship presidents via email, with two follow-up emails inside of a month, to both the president’s email address and his or her executive assistant. Eight presidents volunteered to speak with us directly, and in four cases the president invited us to speak with vice-presidents of communication, pointing out the large role that the communication executive had in crafting public statements. The eight presidents who spoke with us validated our decision to include the comments of the vice-presidents of communication, as all agreed that the communication office worked in tandem with the president both in the decision to make a statement and in crafting of their messages.

A challenge that we faced as researchers was providing thick, rich descriptions of the participants (Merriam, 1998) while protecting their identity and preventing deductive disclosure (Kaiser, 2009). Since there were only 50 potential participants, detailed descriptions of the participants such as gender, time at institution, institutional enrollments, or institutional locations (e.g., rural, urban) may make them identifiable, thus careful steps were taken to avoid disclosure. Participants are only referred to by their title and a letter (e.g., President A), and only general descriptions are given for the whole sample, avoiding specific details which can be pieced together to determine identity.

Interviews were between thirty-five and sixty minutes long, and questions focused on their experiences with and perceptions of presidential communication using a semi-structured set of interview questions (Seidman, 2013). Interview questions were developed based upon the theoretical framework as well as the literature on presidential leadership and communication (See Appendix B for the list of questions). Follow-up questions were asked to seek additional information, clarification, or a deeper understanding (Seidman, 2013). Interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis by a professional transcriptionist. The transcripts were then reviewed by a member of the research team for accuracy. Names of the participants and their institutions were replaced with pseudonyms in the final transcripts.

Data analysis happened in two phases to enhance trustworthiness. Data was first unitized into the smallest meaningful piece of information (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and coded using open and axial coding (Saldaña, 2016) to establish themes independently by two members of the research team. In the second phase, one member of the research team compiled the resulting analysis from the two researchers into one Excel document for review. The two members of the research team came together to compare, discuss, and agree on themes and subthemes from the combined document. After agreeing on the resulting themes, a peer-debriefer reviewed a subset of the data and the findings section to confirm the findings (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The findings presented below represent the final, agreed upon analysis. Additionally, audit trails of analyzed and unanalyzed data were kept for the trustworthiness of the study, specifically confirmability and dependability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Findings

President participants for this study had all been in their current role for less than 10 years, with the average of four years in the role. However, the eight presidents who participated in the study had a total of 74 years of experience as president at many different institutions. Vice-president participants ranged in time in their roles from two to four years and all had experience as communication professionals outside of higher education. Participants came from institutions across the United States, representing different socio-political and institutional contexts (e.g., rural, suburban, and urban).

The Role of the President in Crafting the Message

The first research question explored how presidents perceived their role in the process of crafting their communications. Themes to answer this research question included the importance of presidential voice, presidential duty to represent the university, and the importance of multiple perspectives in crafting communication.

Presidential voice. Participants in this study noted the importance of maintaining their presidential voice in the communications coming out of their offices. For example, President A, stated, “I will tell you that most of the time people say to me that if it’s in my voice and it doesn’t sound institutional, then it works much better.” Further elaborating, President A went on to explain the difference between types of communication when choosing to use one’s own voice:

If I do something that has a certain amount of formality to it, the opening of commencement, that’s fine if somebody else writes it for me. But if I’m doing something that’s of significance for the university, I have to write it myself…I take that voice. I think it shows that when you believe what you’re saying as opposed to thinking you’re doing a job.

This explanation highlighted how presidents perceive their role as the communicator and crafter of communication in the context of the setting of the message.

President C provided additional context of this while sharing an example in which the public affairs unit was opposed to the president making a statement concerning a protest on campus:

They didn’t want me to make a response back, and I overruled them on it. Then they wanted me to do a pretty vanilla draft, and I overruled them on that. And so we went back and forth quite a bit wordsmithing the language, but eventually, what you heard was my language.

In the end, President C perceived that it was critical that the message be in a personal voice so that stakeholders could sense the passion held for the topic. Despite this instance of going against council, President C noted that others should be involved in the process, such as the provost or chief student affairs officer, but in the end the president signs their name, and it should be in the President’s voice. Other presidents similarly perceived that they needed to own the voice with which messages were going out, particularly around challenging or important topics. For instance, President H felt compelled to personally write messages, particularly when communications involved issues central to the university. Sharing an example of a free speech debate on campus, the president noted that others were involved in the discussions about statements that were made, but in the end, it was important for the message to be in the language of the president, making the president the primary writer of the message. In both the cases of Presidents C and H, there was a clear link between the importance of the content of the message and the role of the president in crafting the message by taking ownership through presidential voice.

While many presidents allow their staff to draft statements for review, some viewed ownership in the impetus to make a statement, and had to be involved from the beginning to the end of the process. President D, for instance, perceived that for issues-based communications, he needed to be the one to establish what was being said, often writing the first draft himself. By doing so, he could ensure that content and message were in line with his voice and intent, noting, “I usually felt the need to really sit down and write that, in a first draft sense, to make sure it was safe, it was addressing the issues I wanted it to address.” Similarly, President G explained how he put his “fingerprints all over it. I want to say this. This is what I want to do,” taking ownership of the voice throughout. The importance of the president’s voice was also articulated by President F who stated, “I mean, in the end, I’m the president. And so it’s my responsibility to communicate on these things.”

Presidential duty to represent the university. Most of the participants in this study highlighted that communications coming from the president’s office did not represent them as an individual, but instead represented the university. Although many of the participants were inclined to write the first draft themselves to maintain the presidential voice, they did not exclude others from the process because the statement represented more than just their individual viewpoint. In each of these cases, after drafting the first version of the communication, the presidents chose to vet it through various groups, including executive teams, communications staff, students, government relations, the legal team, and external reviewers.

Some presidents also argued that the sector of their institution also played a part in how they felt they could respond. While discussing a politically charged policy that one university wanted to weigh in on, President H stated, “…there’s something that comes along with having been at a public institution that inflicts at every level the way we think about who we are, what we are, what we are in relationship to our peers….” President H further clarified that the very nature of a public institution had to become a part of who they were as a leader and inform their communication process.

Similarly, President A emphasized the importance of recognizing the difference between one’s own opinion and that of the office of the president, explaining, “I might think I have the right to express it [opinion], but I am not myself as an individual. I am representing the university.” When considering the power of a presidential communication, President G highlighted that a president’s communications should never put the institution at risk, stating, “I’m pretty careful to make sure I don’t put the university in a position where I have to either defend it or somebody has to defend it in a court of law.” Despite owning their voices, participants were cognizant of the fact that their voices as presidents were tied to the university, and as such, they were not communicating as individuals, but as representatives of the institutions they served. As a result, it was their responsibility to include others in the communication crafting process.

President F also argued that the president’s responsibility to the institution was very different than that of other employees:

So if one of my faculty members wants to put up a President Trump or a Donald Trump for president sign in his or her office, they’re free to do that. I’m not. That’s very clear from Supreme Court rulings, and the reason…the reason is that if I do that, then from an employment perspective, my subordinates…would say, “Oh, I have to align with that or I might be acting against my university president’s wishes and that could result in an adverse employment action.” So there’s a real different legal constraint on presidential expression than on, at least, faculty expression.

This example illustrates how presidents can feel added pressure and responsibility to consider their positions in crafting communications, while constituents may not even recognize that constraint. Said another way, the presidents, in this study acknowledged that even what they choose to respond to or communicate about is in some ways constrained by their role within the university. As a result, the process of crafting the communication often helps presidents discern if the topic and/or content is appropriate for the president, and in turn the university, to take a position.

Multiple perspectives in crafting communication. Participants also perceived one of their roles to be engaging others in the process of crafting presidential communications. President F illustrated the importance of this theme explaining, “I do think it’s extremely helpful to have help on your communications….on important communications, it’s very important to involve other people and get their ear.” President H highlighted that by asking others to read drafts, a president might be able to prevent a misstep due to misunderstanding of intent:

Don’t be shy in asking people to read drafts. It’s always good to—especially when you’re starting—it’s always good to see how people read your language. You may think you’re being completely sincere, but it may come across as insincere. You may think you’re tapping into how students think about the world, and it may actually mark you off as somebody who doesn’t know what the heck is happening with students…It’s important to have a sense of how different members of the community really do read, respond, and understand what your trying to accomplish.

The presidents outlined a number of different stakeholders and perspectives that they sought to gain perspective from throughout the communication crafting process.

Even when advocating for their role in the crafting of messages, a group of presidents noted that it was important for a president to recognize that they are not a media person themselves. President B noted that communications should be written by media experts, something that he did not perceive to be the role of the president, stating:

Find a media person that you can really trust. Because in the end, they’re going to craft something. Don’t craft it yourself because we’re not media experts. That should never be done. We need to get somebody that has experience doing this.

Whether arguing for a media person or not, all presidents claimed that they were never the solo author of their communications. The complexities of the issues they faced and the hectic pace of their role necessitated utilizing a team.

Who Is Involved in Crafting the Message and What Are Their Roles?

The second research question examined who was actually involved in the presidential communication process and their various roles. After careful analysis of the results, findings indicated that people involved in the development of presidential communication depends on the type of message and whether it is routine or complex. The participants in this study frequently used “we” to frame discussions surrounding presidential communications, highlighting the complexity and the multiple voices that were involved in the process. The type of statement (e.g., routine, day-to-day issue versus complex, unique issue) also factored into how a statement was crafted and who was involved. As President D noted:

It varies depending on what the statement is. If the statement is something that is much more routine, I usually craft the statement myself and then run it through my communications team and my senior leadership team to vet…If it is an issue-based communication…that’s meant to address a particular issue, then typically we’ll outline what I want the statement to be, and then our communications folks will finesse that.

In discussing the participants involved in crafting presidential communications various stakeholders and perspectives were identified, including the chief of staff, executive team (e.g., vice president of student affairs for issues involving students, provost, vice president of business/finance), communications personnel, legal counsel, and external reviewers (e.g., peers, consultants). Each individual or group had a specific role within the process according to the participants in this study, such as helping to draft, refining wording, targeting the message to specific constituent groups, vetting the message, and making sure the message was compliant with legal requirements.

Chief of staff. More than half of the president participants identified the chief of staff’s role in drafting presidential communications. In many cases, the chief of staff served as the initial draft writer, apart from the president. For instance, President B noted, “They [communications] usually start with my chief of staff. And she comes from the media relations world.” This was echoed by President F who utilized his chief of staff for both writing drafts and vetting the message, stating:

I also do rely pretty heavily on my chief of staff, who is herself an excellent writer. But also, I often rely upon her more for kind of asking the questions, “Well who is the audience and what are they wanting to hear about this topic? How do they feel when they get this?”

President F also reflected that depending on the size and resources of the institution, there may not be a formal communications team, leaving those responsibilities initially with the chief of staff. For most of the president participants, the chief of staff was an integral part of the vetting process to ensure the communication aligned with the intended meaning.

Executive team. Following the chief of staff was the importance of including the executive team or cabinet in communication drafting and decisions. President A shared how communications were crafted surrounding a recent issue with Greek life, noting that there was “lots and lots of communication around my executive team about what we’re doing, what we should be saying and things like that.” The president then talked about who among the executive team were important to include in the crafting of the message, such as the vice president of student affairs due to the fact that it was a student issue and the provost to represent the academic side.

Vice President A identified the provost, chief of staff, chief diversity officer, and the vice president for communications as critical to the discussion and drafting of past messages. President H said that executive team members were brought in for their expertise and knowledge, especially surrounding specific issues or constituent groups. However, some presidents felt they could handle the communication crafting if the issue was common, as President D noted, “If a statement is something that’s much more routine, I usually craft the statement myself, and then run it through our communications team and my senior leadership team to vet it.”

Presidents also needed the executive team to delegate who gave the final message. As President C explained,, “Don’t go it alone. You and the team need to understand when does the president speak, when is it the provost speaking, when is it the vice president for student affairs. I mean, there’s a lot of people who speak.” Delegating who authors the message was important so the President’s name and voice is not overused. As Vice President C explained, “I think other senior leaders are willing to help carry the weight, and not make the president the one that’s always paraded out when something bad happens.”

Communications staff and vice president for communications. As noted in the methods section, the role of the vice presidents for communications was evident since presidents at four institutions directed us to interview the vice presidents of communications instead. One vice president for communication reflected on the process of crafting presidential communications at his institution, and noted that while communications staff almost always engaged in developing formal communications (e.g., speeches, “broad campus messages”), often the president took the lead in informal communications (e.g., open microphone events).

Communications staff were frequently involved in the drafting process, where they often created a draft based on one conversation with the presidents. President C described his relationship with his chief speechwriter, noting, “He and I have had a conversation first and he says, ‘What do you want to say?’” Other participants noted the role of the communications staff in taking what a president wrote and adjusting the tone or refining the statement with the intended audience in mind. Vice President B shared an example in which his president was a great academic writer but sometimes used too formal or complex language when communicating with certain stakeholder groups. As a result, he stated, “We will shift his tone or even some of the language that he uses.” President D specifically credited the communications team with adjusting language, noting, “And then they’re making it [the language] more eloquent and taking out any [dialect] I might have hit…vernacular. Our folks make it sound better.”

Being able to mimic the President’s voice was an important skill for communication personnel. President F explained, “I have this [communications] person with whom I work very closely. And I would say he has a good understanding of what I would call my voice.” This was reiterated by President E, stating:

[My university relations person] really has to understand what’s inside my head and to be able to catch my voice, because I don’t want it to look like it was written by someone else, or that it was just a mimeographed, rote answer. So I try to have consistency in the way that my language sounds, as well as the message itself.

For each president, it was critical that the communication staff could maintain the president’s voice.

Legal staff. More than half of the participants noted the role of legal involvement in the communication process, particularly for messages which were complex. Presidents who mentioned legal staff unanimously agreed that the role of legal staff was to vet the message and reduce institutional liability. President A explained, “It’s important for legal counsel to look at it because, okay, there could be court cases, and am I saying something that would frighten them?” President G noted how legal counsel can prescribe realistic limits, saying, “If it’s a legal issue, if I’m dealing with, immigration or something, I have the legal office look at it to check to make sure that I’m not saying something I can’t do.” Even one president who has a background in law perceived institutional legal counsel as a critical part of the communication process.

External reviewers and other perspectives. External reviewers were also key players for vetting messages. Vice President C explained the importance of getting outside perspective by observing, “I think….one of the reasons we have landed in the wrong place at times is when we become too insulated or too much in our own bubble.” President B described these external reviewers as “reputation protectors,” further elaborating:

I really find the most value with the outside consultant I was talking about, a bumping off of somebody or having somebody react and read to it who’s not in your institution that would look at it as a person in the general public would look at it. And they do, I understand what this person is trying to communicate. I changed statements because of input that’s come from the outside that says, “Yeah, you might be good for the half a dozen people that want you to write this, but think of the implications more generally across the state or across the country because people do pay attention to these.”

The external reviewers took on various forms. Sometimes they were still internal to the institution, yet not involved in the process (e.g., student government president) and other times they were completely external to the institution.

Discussion

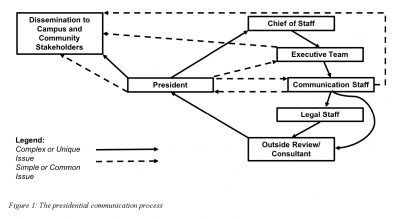

As the pressure for timely presidential communication increases due to the 24 hour news cycle (Selingo et al., 2017), better information and training will be needed to prepare executive leaders. In this study, we draw on the perceptions of public flagship university presidents to explore the communication process of these critical leaders. Our findings indicate that the process for communication is context specific, and that there are a number of individuals collaborating with the president to craft presidential communications. As illustrated in Figure 1, if the issue is simple, the president will only engage one specific person, or team, such as the communication vice-president and staff. However, in more complex situations, the president will engage all members of their leadership team to ensure that the communication is both necessary and properly crafted.

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model derived from our findings, and informed by the cognitive process theory of writing (Flower & Hayes, 1981). The solid line indicates the process for complex or unique issues where the president discusses the issue with key stakeholders such as the chief of staff, executive team, or legal counsel prior to disseminating the message to the community (e.g., immigration, free speech). The dotted lines illustrate a series of potential processes for responding to common issues (e.g., routine or daily communications). Our finding that the communication crafting process differs based on the complexity of the issue aligns with the work done by Knapp & Hulbert (2017), which focused on CEOs in business. Specifically, the president could connect with only the communication team, and in some cases, even have them send the message to the campus community. In other common instances where common challenges require presidential communication, they may engage the executive team and have members of that team deliver messages. Our findings add to the research done by Eddy (2003, 2005) who argues that presidents are sensemakers on their campus, as we find that the role of sensemaker is likely a collaborative process between the president and various stakeholders. Utilizing many perspectives in the process of communication crafting helps presidents to be better informed and more capable of providing constituents with direction and insight. Further, our results indicate that even the process of identifying the person who will speak is an aspect of how communication should be interpreted on their campus, as presidents posit that their responses should be limited to critical issues that affect the whole campus.

Likely the most salient result of this study is that crafting an effective message is a process. Aligning with the four elements of the cognitive process theory of writing, we first find that presidential communication is an organized act by these leaders (Risemberg, 1997) where presidents develop certain heuristics that guide who reviews, drafts, and approves their communication early in their presidency. Second, we find that communication crafting is an embedded process where each person involved, or decision made, informs the next (Perrin, 2006). This was evident when comparing simple and complex issue communication. Instances where the issue was common or simple, the president spoke to the communication team who then sent it out or sent it back to the president. In contrast, when the issue was complex, presidents would often begin with the chief of staff, then pass it through their executive team, and resembled a much more structured process. Third, previous research has illustrated that presidential communication is often goal oriented (McNaughtan & McNaughtan, 2019; McNaughtan et al., 2019), and our results indicate this as well as illustrated by the decision to have the right person speak on specific messages. Finally, Flower and Hayes (1981) discuss how the main goal of the process is supplemented with a series of smaller goals that lead to an iterative process. All participants in our sample discussed the multiple iterations of presidential communication, highlighting this aspect of the theory.

Implications for Practice

There are a number of potential implications for practice resulting from this exploratory study. First, presidents should embrace the process. Our findings highlight the importance of involving others in the communication process, as it can provide additional perspective and ensures that the president utilizes the expertise hired to support the president. In connection with the work of Zainontz (2015) on presidential twitter accounts, our findings align with the idea that even when the president takes on the brunt of communication crafting, the perspective of others is needed.

Second, presidents need to be cognizant of their strengths and rely on their team when communicating. Presidents highlighted the use of internal and external communication professionals that can help to inform the creation of communication. As Pierce (2012) argued, presidents must choose their words carefully, especially during exceptionally complex issues. Participants agreed, as they believed message should not just represent their own voice, but also that of the institution they serve.

In connection with relying on those with expertise, leaders in higher education should be reflective of when to communicate, and who should communicate. Participants in our study discussed the importance of having the appropriate person speak. Thus, depending on the issue, various executive team members could be tasked with addressing campus stakeholders. This could be helpful when presidents are developing communication skills (McNeal, 2013) and to help president address the wide variety of consistently arising challenges at the institution (Selingo et al., 2017).

Finally, our conceptual framework (Figure 1) can be seen as a way to view the feedback in the presidential communication process. Similar to organization charts, presidents could develop a communication process chart that outlines the role of each participant in the process, highlighting the difference between communication types (complex versus common). For example, the chief of staff was often perceived as the person the president discussed whether communication was necessary and the executive team could be where the president decided who should communicate the president’s message. Each participant of the conceptual framework could have a defined role which could ensure an efficient and productive process, where important feedback is given during the message crafting process.

Conclusion

The presidential communication process is incredibly complex. As leaders of colleges and universities are increasingly expected to communicate about both institutional and societal challenges, it will be important for their communication crafting process to be refined and informed. In this study, we find that presidents differentiate common challenges from big issues and that their communication crafting process is different, depending on the level of complexity of the issue. In addition to discussing best practices for communication development using the cognitive process theory of writing, we provide a process model of communication for institutional leaders to both utilize in practice, and for scholars to test when considering how presidents develop messages to their communities.

References

Americ, J., & Craig, R. (2007a). Improving CEO-speak. Journal of Accountancy, 203(1), 65-66.

Americ, J. H., & Craig, R. J. (2007b). Guidelines for CEO-speak: Editing the language of corporate leadership. Strategy & Leadership, 35(3), 25-31.

Americ, J., Craig, R., & Tourish, D. (2010). Measuring and assessing tone at the top using annual report CEO letters. Edinburgh, Scotland: The Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland.

American Association of Community Colleges. (2013). AACC competencies for community college leaders (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/AACC_Core_Competencies_web.pdf

Barnes, N. G., & Lescault, A. M. (2014). College presidents out-blog and out-tweet corporate CEO’s as higher ed delves into social media to recruit students. Retrieved from https://www.umassd.edu/media/umassdartmouth/cmr/studies-and-research/CollegePresidentsBlog.pdf

Barrett, D. J. (2014). Leadership communication (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Bastedo, M. N., Samuels, E., & Kleinman, M. (2014). Do charismatic presidents influence college applications and alumni donations? Organizational identity and performance in US higher education. Higher Education, 68(3), 397-415.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). An attainable version of high literacy: Approaches to teaching higher-order skills in reading and writing. Curriculum Inquiry, 17(1), 9-30.

Cole, E. R. (2015). Using rhetoric to manage campus crisis: An historical study of college presidents’ speeches, 1960-1964. International Journal of Leadership and Change, 3(1), 11-18.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Eddy, P. L. (2003). Sensemaking on campus: How community college presidents frame change. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 1(6), 453-471.

Eddy, P. L. (2005). Framing the role of leader: How community college presidents construct their leadership. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 29(9-10), 705-727.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College composition and communication, 32(4), 365-387.

Freeman, S., & Kochan, F. K., (2013). University presidents’ perspectives of the knowledge and competencies needed in 21st century higher education leadership. Journal of Educational Leadership in Action. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.846.2305&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Gagliardi, J. S., Epsinosa, L. L., Turk, J. M., & Taylor, M. (2017). American college presidents study 2017. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Hayes, J. R. (2006). New directions in writing theory. Handbook of writing research, 2, 28-40.

Hodson, J. B. (2010). Leading the way: The role of presidents and academic deans in fundraising. New Directions for Higher Education, 2010(149), 39-49.

Kaiser, K. (2009). Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 19(11), 1632-1641.

Knapp, J. C., & Hulbert, A. M. (2017). Ghostwriting and the ethics of authenticity. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Legon, R., Lomardi, J. V., & Rhoades, G. (2013). Leading the university: The roles of trustees, presidents, and faculty. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 45(1), 24-32.

Len-Rios, M. E. (2010). Image repair strategies, local news portrayals and crisis stage: A case study of Duke University’s lacrosse team crisis. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 4(4), 267-287.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Longmire, J. (2013). Presidential derailments at public master’s level institutions. In S. J. Trachtenberg, G. S. Kauver, & E. G. Bogue (Eds.), Presidencies derailed: Why university leaders fail and how to prevent it (pp. 35– 49). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

MacMillan, S. (2012). The promise of ecological inquiry in writing research. Technical Communication Quarterly, 21(4), 346-361.

McNaughtan, J., Garcia, H., Lértora, I., Louis, S., Li, X., Croffie, A. L., & McNaughtan, E. D. (2018). Contentious dialogue: University presidential response and the 2016 election. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1462437

McNaughtan, J., Louis, S., García, H. A., & McNaughtan, E. D. (2019). An institutional North Star: the role of values in presidential communication and decision-making. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41(2), 153-171.

McNaughtan, J., & McNaughtan, E. D. (2019). Engaging election contention: Understanding why presidents engage with contentious issues. Higher Education Quarterly, 73(2), 198-217.

McNeal, J. (2013). Presidential derailments at private liberal arts institutions. In S. J. Trachtenberg, G. S. Kauver, & E. G. Bogue (Eds.), Presidencies derailed: Why university leaders fail and how to prevent it (pp. 21– 34). Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education,(2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Papadimitriou, A. (Ed.). (2018). Competition in higher education branding and marketing: National and global perspectives .London, UK: Springer.

Perrin, D. (2006). Progression analysis: An ethnographic, computer-based multi-method approach to investigate natural writing processes. In L. Van Waes, M. Leijten & C. M. Neuwirth (Eds.), Writing and digital media (pp. 73–79). Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier.

Perrin, D., & Wildi, M. (2010). Statistical modeling of writing processes. In C. Bazerman et al. (Eds.), Traditions of writing research (pp. 378–393). New York: Routledge.

Pierce, S. R. (2012). On being presidential: A guide for college and university leaders. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Plinske, K., & Packard, W. J. (2010). Trustees’ perceptions of desired qualifications for the next generation of community college presidents. Community College Review, 37(4), 291-312.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Seeger, M. W. (1992). Ethical issues in corporate speechwriting. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(7), 501-504.

Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as Qualitative Research, (4th ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Selingo, J. J., Chheng, S., & Clark, C. (2017). Pathways to the university presidency: The future of higher education leadership. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/3861_Pathways-to-the-university-presidency/DUP_Pathways-to-the-university-presidency.pdf

Smerek, R. (2011). Sensemaking and sensegiving: An exploratory study of the simultaneous ‘being and learning’ of new college and university presidents. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 18(1), 80-94.

Smith, Z. A., & Wolverton, M. (2010). Higher education leadership competencies: Quantitatively refining a qualitative model. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17(1), 61-70.

Stake, R. E. (2008). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (pp. 119-149). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Trachtenberg, S. J., Kauver, G. B., & Bogue, E. G. (2013). Presidencies derailed: Why university leaders fail and how to prevent it. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Vitullo, E., & Johnson, J. (2010). University presidential rhetoric and the 2008-2009 economic crises. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 32(5), 475-485.

Zaiontz. D. (2015). #Follow the leader: Lessons in social media success from #highered CEOs. Saint Louis, MD: EDUniverse Media.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: A social cognitive perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22(1), 73-101.

Appendix A

Interview Protocol

- Do you think your public communications (e.g., email, blog posts, interviews, etc.) are influential on the campus community and public?

- Following the 2016 presidential election, college presidents across the country sent out emails related to the election. Did you send out an email or any form of public communication after the election that could be perceived as related to the outcome of the election?

- What motivated you to send out a public response?

- Was anyone else involved in crafting the statement, and how did they contribute?

- Was there pressure to send or not to send a public response? If so, who?

- What has been the response from the campus to your public statement?

- What has been the response from the external community to your public statement?

- Did the context of your institution (e.g., red/blue state, size, location, etc.) have any influence on your public response?

- What are some of the reasons you feel presidents should make public statements, like the one sent out after the 2016 Presidential Election?

- What advice would you have for new presidents on how to craft public statements?

- Are there any additional questions you feel like we should have asked that we did not?

Figure 1: The presidential communication process