Pathways to the Urban Community College Presidency

Everrett A. Smith

University of Cincinnati

Correspondence related to this article should be addressed to Everrett A. Smith, Assistant Professor, Higher Education, University of Cincinnati, everrett.smith@uc.edu

College presidents have multiple, complex roles. These roles have evolved to include an increased emphasis on external relations, regardless of institutional type, yet these leaders are also expected to hold traditional academic credentials. This study explored the experience base of urban community college presidents and found that they hold remarkably similar skill sets and experience backgrounds to other college presidents.

Historically, the community college has operated as an institutional mechanism for access to postsecondary education. Specifically for community colleges in urban areas, there are unique challenges in how they accomplish the traditional mission of the community college. This is associated with their locality to major cities, which are often more complex living environments with pronounced challenges around taxes, education, crime, and socio-economic inequities (Myran & Parsons, 2013; Hirose-Wong, 1999). However, urban community colleges play a critical part in serving a wide array of students, many of whom are from various backgrounds as well as the immediate metropolitan area in which the community college exist (Hagerdorn, 2004).

Perhaps as important is the role of the urban community college president. This leader has the distinct responsibility for managing and leading an institution that competes for both local and state funding to support institutional priorities that include instructional costs, institutional scholarships, creating new academic programs, and capital projects (Smith & Miller, 2015). Several pieces of literature have explored the college presidency at traditional four-year colleges and universities (Smerek, 2013; Birnbaum & Umbach, 2001; Moore, Salimbene, Marlier, & Braggs, 1983; Cohen & March, 1974). While these works have highlighted the challenges four-year college presidents and their institutions face, the exploration of the role of the two-year urban community college presidency has been relatively underexplored. This study examined the professional path of the urban community college president, including profiling the steps that individuals have taken to assume a presidential role.

By analyzing curricula vitae of 25 community college presidents at urban institutions, multiple variables were examined including academic background, professional background, past and current fundraising responsibilities, and institutional enrollment. Ethnicity and gender were also considered in the analysis. The purpose of the study is to help stakeholders better articulate and set expectations for leaders in this role, and for those leaders to do the same. At the same time, potential and current college leaders will be able to better position themselves to serve as community college presidents in urban environments.

Background of the Study

The college presidency has evolved over the past 40 years. College presidents have historically ascended from academic backgrounds, usually from that of a provost, and less frequently, college dean. Once a position that often involved more curricular and disciplinary responsibilities (Riles, 2001), the role of the American college president has begun to include increasingly more responsibilities centered around external activities. College presidents invest their time into managing the expectations of external stakeholders such a state legislators, donors, and board of trustees (Selingo, Chheng, & Clark, 2017). Because of the complexity of the college president’s role today, the ability to lead is demonstrated in much more general and stylistic ways, thus requiring leadership and communication skills rather than a distinctive set of technical skills.

Individuals who lead traditional four-year colleges and universities often face a heightened variety of praise and scrutiny in the position. This mixture of criticism and recognition are expected at traditional four-year institutions, especially state flagship and prestigious private universities, because they are often viewed as some of the leading institutions in American higher education. However, several community colleges have been in the news for their efforts towards providing students open access to postsecondary education (Shannon & Smith, 2006). Oppositely, confrontation with board of trustees, improper use of funds, and negative findings in audits have placed the community college, at times, in negative view (Smith, 2016).

In the past, attributions to the perceptions of the city community college have often been presented in pop culture as a second-tier option to pursue postsecondary education (Moltz, 2009). Community college presidents are commonly charged with discouraging this frame of thinking and improving the reputation of the college. In addition, partially due to the Obama Administration’s public commitment to community colleges, Americans increasingly view four-year and two-year institutions as having similarities in quality and curriculum offerings (McCarthy, 2015).

The urban community college president has also had the difficult task of managing a complex organization in a diverse city environment. Leading these types of institutions requires nimbleness and adaptability (Thomas, 2013). Presidents who lead two-year institutions and presidents of traditional four-year colleges, particularly in urban settings, face similar complexities in their roles. For example, urban community colleges not only have to compete for public fiscal support, but also directly and indirectly, address city issues that impact their student population (Myran & Parsons, 2013). More importantly, urban community colleges typically serve a different type of student body, as many students who attend community colleges arrive from underserved populations. Studies show that a substantial number of students attending a community college are students of color (Ma & Baum, 2016), and over 40 percent are first- generation students (NCPPHE, 2011).

Urban community colleges share the experience of attempting to provide best services and curricula to a diverse community while serving as agents for social change in their metropolitan area (Hirose-Wong, 1999). They tirelessly attempt to find creative ways to collaborate with the city in which they inhabit to effectively serve their students and best use institutional resources. This is partially attributed to the lack of diverse private resources that they receive (Smith, Miller, & Gearhart, 2017). Approximately 75 percent of private resources donated to a community college come from private industry rather than individual donors (Myer, 2014). Many of the programs developed with these types of supports involve creating private workforce education training models. Though this may help the community college, students, and company donors, little of these types of gifts are used for operating funds. Community college presidents compete and advocate for contracts and private programs that support the institutional mission, and the president’s vision and goals for the college.

Research Methods

The data were collected by identifying community colleges located in the 25 largest urban metropolitan areas in the United States. A sample of metropolitan areas were identified based on the Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSA) listed by the United States Office of Management and Budget (2017). The community colleges that serve each MSA were identified through the American Association of Community College’s (AACC) website that included a “community college finder;” a search engine for locating community colleges across the United States. Each institution was selected based on either being the only community college serving the MSA or the primary community college serving the MSA. Institutions, including those that were a part of a community college system, were determined to be the primary community college campus in the area based on largest student enrollment, public designation, and historical presence in the area.

The president of each selected community college was identified from the institution’s website. After identifying the college president, the individual’s curriculum vitae was accessed for analysis. If the identified president’s curriculum vitae was unavailable, biographies located on the institutional website and other trade periodicals including Community College Week, Inside Higher Ed, and the Chronicle of Higher Education were used to determine each subjects’ professional and academic background and demographic information.

Each community college president’s curriculum vitae was analyzed for the purpose of the study with the following variables considered: academic degrees attained, professional background, history of involvement in fundraising activities, size of student enrollment at the community college, and previous history of serving as a community college president. The comprehensive nature of each curriculum vitae, or lack thereof, created limitations for the study, including that each president might not have provided complete, accurate, and detailed information on past work performance and professional experiences.

Findings and Analysis

The researcher attempted to collect the curriculum vitae of each community college president. In addition, biographies on the community colleges’ websites were used in order to analyze the professional backgrounds of the presidents. Also, trade publications and social media websites, such as LinkedIn were used to identify missing information about each president such as academic degrees earned, salary, and previous work experience. Eight of the college presidents were women and 17 were men. Of the community college presidents, 23 (92%) of them earned a doctoral degree, with the majority being an Ed.D. or Ph.D. Fourteen presidents held an Ed.D., one president held a D.A., and two presidents held master’s degrees. Eight presidents held a Ph.D., and four of the doctorates represented an academic discipline other than education or higher education administration.

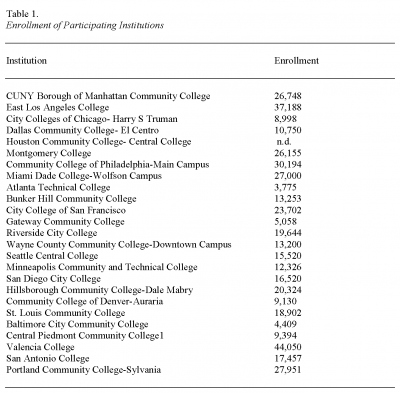

Of the presidents in the study, 14 served as a community college president at least once before their current role. One individual held the role of provost and presided over a single campus with the same job responsibilities as the other community college presidents in the study. Published details about each president’s fundraising experience were limited. Many of the analyzed artifacts referenced the presidents’ experiences with securing external grants or state support for workforce initiatives such as transit, facilities upgrades, and specialty equipment for career preparation. Salaries of presidents varied, and there was little distinction between community colleges with larger student enrollment, fundraising experience, and salaries of the president. Presidents of community colleges located in the largest urban metropolitan areas tended to have slightly higher salaries. The average salary among all community college presidents in the study was $ 211, 208. For those community college presidents whom salaries were not published, the researcher attempted to identify the salary of the presidents’ predecessors in order to determine a proxy. Salaries of the college presidents at Gateway Community College, Minneapolis Community and Technical College, and Community College of Denver-Auraria were not included in the salary average. The average student enrollment of all included institutions was 36, 132 (see table 1). Enrollment data for the Houston Community College main campus was not located and therefore not included in the enrollment average.

Discussion and Conclusion

Though there are several pathways to the urban community college presidency, academic affairs and student services roles continue to be more common. This may be attributed to the nature of the presidency role and mission of the community college. Community colleges as a larger part of the higher education industry continue to invest in and support programs and services that contribute towards workforce development. This is especially relevant because urban areas tend to address poverty and unemployment with educational efforts. Due to their structure and size, metropolitan areas host major U.S. companies, and many residents hold a college degree. This culture of postsecondary attainment is influential on a large metropolitan area, and so, community colleges have opportunities and motives to reach underserved populations.

Fundraising is a modern and expected skill set for four-year traditional college presidents, but was less highlighted in the community college presidents’ biographies and sporadically included on presidential CVs as experience. Very few led a capital campaign, but all of the presidents included their budgetary and personnel experiences. All of them managed budgets over $10 million.

Direct experiences working with students in teaching and administrative roles are still valued, and though some community college presidents come from business or health administration backgrounds, the importance of customer service is implied if not explicit in their messaging. Perhaps the most common theme that helps characterize the urban community college presidency is the ability to lead through advocacy. Being aware of the type of student served is critical for success. Multiple media artifacts suggested that many of the community presidents examined in the study were first-generation students, which certainly could be useful for conveying a message with passion and authenticity when seeking to become a president.

Additionally, an earned doctorate was common and likely required to be considered for the position. The earned doctorate could be more symbolic to students, sending a message about academic perseverance. People of color and women were predominant in these presidential positions, which also represents the diverse population that urban community colleges serve.

The college presidency has developed into a competitive, complex, and truncated role. Less presidents are staying in their role at urban community colleges, and instead, are finding themselves serving long enough to demonstrate accomplishments that are recognizable to the next institution of interest and located in a similar setting. For leaders interested in leading a community college campus in a larger city, demonstrating ones’ abilities in an academic or student oriented role at a similar sized institution, or holding a presidency role at a college in a smaller city could appropriately prepare one for the college presidency at larger urban institutions like those in the study. The urban community college is arguably a part of a niche market. The diverse student population served, necessary state and local competition for funding, influential city politics, and socio-economic challenges make for a different type of managing environment for the college leader.

References

Birnbaum, R. & Umbach, P. D. (2001). Scholar, Steward, Spanner, Stranger: The Four Career Paths of College Presidents. The Review of Higher Education 24(3), 203-217.

Cohen, M. D., & March, J. G. (1974). Leadership and ambiguity: The American college president. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Hagedorn, L. S. (2004). The role of urban community colleges in educating diverse populations. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2004(127), 21-34.

Hirose-Wong, S. M. (1999). Gateways to Democracy: Six Urban Community College Systems. ERIC Digest. Retrieved from ERIC database. ED438873

McCarthy, J. (2015). Americans View Quality of Two-Year, Four-Year Colleges Similarly. Gallup News. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/183779/americans-view-quality-two-year-four-year-colleges-similarly.aspx

Ma, J., & Baum, S. (2016). Trends in community colleges: Enrollment, prices, student debt, and completion. New York: College Board Research. Retrieved from https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-in-community-colleges-research-brief.pdf

Moore, K., Salimbene, A., Marlier, J., & Bragg, S. (1983). The Structure of Presidents’ and Deans’ Careers. The Journal of Higher Education, 54(5), 500-515.

Myers, H. (2014). Capital campaign strategies you may be missing: What’s new and what’s working for institutions engaged in capital campaigns. University Business

Myran, G. and Parsons, M. H. (2013), Overview: The Future of the Urban Community College. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2013: 7–18. doi:10.1002/cc.20054

Moltz, D. (2009). Colleges Review ‘Community’. Inside HigherEd. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/08/24/community

Rile, J. A. (2001). The changing role of the president in higher education. New Foundations. Retrieved from https://newfoundations.com/OrgTheory/Rile721.html

Selingo, J., Chheng, S. Clark, C. (2017). Pathways to the university presidency: The future of higher education leadership. Retrieved from: https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/industry/public-sector/college-presidency-higher-education-leadership.html

Shannon, H. D. and Smith, R. C. (2006), A case for the community college’s open access mission. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2006: 15–21. doi:10.1002/cc.255

Smerek, Ryan. (2013). Sensemaking and New College Presidents: A Conceptual Study of the Transition Process. The Review of Higher Education, 36(3), 371-403.

Smith, A. (2016). Tension at the Top. Inside HigherEd. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/05/20/many-community-college-presidencies-are-upheaval

Smith E. A., & Miller, M. T. (2015). Presidential perceptions of trustee involvement in community college decision making. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(1), 87-94.

Smith, E. A., Miller, M. T., & Gearhart, G. D. (2017). Using Feasibility Studies in Capital Fundraising Campaigns: A National Survey of Community Colleges. Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 24(2), 15-27.

The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education (2011, June). Affordability and Transfer: Critical to Increasing Baccalaureate Degree Completion. Retrieved from http://www.highereducation.org/reports/pa_at/PolicyAlert_06-2011.pdf

Thomas, G. A. (2013). The community college president and the new norm: Perceptions of preparedness to take an entrepreneurial stance in seeking ethical alternative funding. Unpublished Dissertation, Iowa State University.

***Editor’s Note: This article is a revision of the original that was published in the Fall 2017 issue. The revisions are included in this version, posted November 2019 at the request of the author.